The alarming situation of the declining birthrate as seen from population data analysis

My specialty, demography, is the discipline of analyzing human behavior through the analysis of demographic factors including age, gender, household structure, academic background, and occupation, etc and focusing on trends of births, deaths, marriages, divorces, and migration, which are factors pertinent to population changes. Using reliable data for examination is essential in demography. Demography is an extremely data-oriented academic field based on the conclusive evidence of facts.

Currently, the biggest and most pressing issue to address is the declining birth rate. Japan’s birth rate has continued to decline for forty years. Keeping a total fertility rate (the average number of children that a woman gives birth to over her lifetime) of 2.07 is considered to allow to keep the replacement rate (number at which the population level can be maintained). “Low fertility” is a phenomenon that the fertility rate continues to be below the sub-replacement fertility rate The total fertility rate was 2.14 in 1973 but it has continued falling since then to a record low of 1.26 in 2005. After that it has reportedly recovered to 1.41 in 2012. However, this does not mean that the government measures worked out to counter the declining birthrate, but that the women of the second baby boomers who had been born between 1971-1974 came to about 40 years old and made various efforts to have children.

The population of mothers is going to decline steadily in the future. If the birthrate continues to remain low at this level, Japan’s population is expected to decline sharply to about 3.6 million people by the year 2300 and this may not only lead to the failure of social security systems including pension plan and welfare but also the nation itself may not be able to maintain its integrity.

The declining birthrate and the unchanged marital birthrate

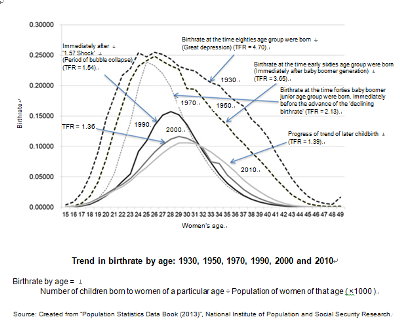

Let’s look at changes in the age-specific fertility rates. The birthrate in 1930, when those currently in their eighties were born, was 4.70. The high fertility (ability to give birth to children) here can be attributed to the fact that women became pregnant and giving birth repeatedly comparatively young and that contraception was not prevalent. Getting pregnant and giving birth is said to reset the mother’s body including the womb and improve fertility. In recent years, the number of mothers who give birth late to their first children is increasing.. However, biologically speaking, women’s eggs age and men’s sperm tend to degrade with age, so the conception rate also tends to decline. There are cases in which women in their mid-forties became pregnant and give birth after fertility treatment; however, this is almost a miracle. The birthrate in 1950, when those currently in their early sixties were born, was 3.65.

In the 1950s to 1960s, there were huge changes in the environment surrounding pregnancy and childbirth. One of those changes was that the notion of contraception started to spread, but, at the same time, there were about the same number of abortions as there were births. Behind these changes was the heightened awareness of caring more for a small number of children, and a social trend that limited the birth of third and fourth children spread. This trend became established in the 1970s and with the further spread of contraception and the so-called “two-child standard” becoming the mainstream for household structure. The birthrate in 1970, when those in their forties were born, was 2.13. Since then, the decline in the birthrate has been advancing in Japan.

However, what we should focus on are not simply the birthrate figures (total fertility rates). In Japan, the rate of extramarital births is low at only 2% of all births. In other words, the actual birthrate is made up of the ratio of “children born from married women” and “the population of married women (women with spouses).” Since 1970, there has been no significant decline in the marital birthrate. That is to say, as long as they get married, most women get pregnant and give birth. Therefore, it follows that the declining birth rate can be attributed to the decline in the number of marriages. The percentage of unmarried women aged 30-34 was 9.1% in 1980, but it has largely increased to 34.5% in 2010. As for those aged 35-39 in the same years, the percentage increased more than four-fold from 5.5% to 23.1%. This trend is the same for men. The percentage of unmarried men between the ages of 35 and 39 was 8.5% in 1980, but it increased to 35.6% in 2010. Considering that married women tend to give birth, the main cause of the declining birthrate is considered to be the rise in the rate of unmarried people. Additionally, the rise in the age of giving birth due to late marriage may decrease the number of birth of the third child as well as that of the second child, which would lead to the issue of infertility. Then, why are the rates of unmarried people, late marriage, and late childbirth on the increase?

The divergence in views towards marriage between men and women stemming from changes in family

Changes in family, more specifically role of family members can be one of the cause of late marriage and late childbirth. During the era of high economic growth, a standard family comprising a father who was the main breadwinner, a mother who was a full-time homemaker, and two children had been as the common form of family. A great turning point came in the form of the 1973 oil crisis. This event brought about a change in predominance from heavy industry to service industry, and that change also affected the family’s way of being. Because mothers started to participate in the labor market of the service industry such as through part-time work, the number of the former standard family began to decline. Moreover, the number of women going into higher education advanced rapidly, and employment opportunities increased further with the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act and other legislation, allowing women the opportunity for economic independence. In the 1980’s the economic bubble enabled mass recruitment and higher wages, which accelerated the trend of increasing number of unmarried people and the late marriage.

Additionally, the war under the “two-child standard”, with no demographic pressure within the household as there was before it became possible for both men and women to live within the economic environment created by their fathers and receive household services from their mothers who, while working part-time, still played the role of a full-time homemaker. According to the 2000 national census, 62.5% of unmarried men between the ages of 20 and 39 and 71.7% of unmarried women lived with their parents. As a result, the tendency for men to pursue women who would play a traditional role in the family grew stronger, while women looked for men who could provide an economic environment and household services such as their parents provided or who would cooperate with them to establish their own households. This divergence between men and women in regard to views on marriage and values make them hesitate to get married.

Securing post-marital economic stability and a family-building environment is necessary

In countering the declining birthrate, measures to curb the advancement of the rise in the percentage of unmarried people and the postponement of marriage should not be discussed within the context of supporting people who are already married and raising a child, such as childbirth support, the daycare waiting-list problem, and increase in children allowances; rather it is necessary to develop an environment which makes it easier for unmarried men and women of a reproductive age to get married and build families. Such measures would have to balance economic stability after marriage and the creation of an environment for family-building. Post-marital economic stability requires regular employment and employment stability after marriage and childbirth as well as the reduction of non-regular employment for both men and women.

To secure an environment to build families, a truly gender-equal society must be realized. That includes rethinking the division of conventional gender-based roles, the independence of men, husbands’ support in housework and child-rearing, child-rearing support linked with community cooperation, and improved after-school care for children. Additionally, the central government, local governments, corporations, and communities must collaborate to enhance the support structure for reproductive health (health related to pregnancy and child birth), such as support for fertility treatment in accordance with the rising childbearing age and the spread of knowledge and implementation of education on reproductive health.

The true purpose of the “women’s handbook” proposed by the Task Force for Countermeasures against Declining Birthrate

Lastly, I would like to touch upon the Cabinet Office’s Task Force for Countermeasures against Declining Birthrate, in which I participate. Masako Mori, Minister of State for Measures for Declining Birthrate, proposes three support measures: child-rearing support, support for balancing work and the home, and support for marriage, pregnancy, and childbirth. As leader of the pregnancy and childbirth review sub-team, the team members and I compiled three measures which had not been touched on before in declining birthrate countermeasures: the dissemination of knowledge and education on pregnancy and childbirth, strengthening of a consultation and support structure for pregnancy and childbirth, and the strengthening of after-birth care.

Of these, the dissemination of knowledge and education on pregnancy and childbirth was taken up by some on the Internet and in the media and criticized, based on a broad interpretation of fragmented information, that the “women’s handbook” was interference by the government in the way women led their lives. However, it goes without saying that that was not the intent, and indeed, it should not be. The idea was based on the Maternal and Child Health Handbook. The Maternal and Child Health Handbook records all medical information from information on the mother during the prenatal period to birth, and until the child grows up. It is a wonderful, world-class Japanese system that links various administrative supports for childbirth and child-rearing. We envisioned a dual structure for the “women’s handbook,” inheriting individual information from the Maternal and Child Health Handbook. The first part would provide information to both men and women on various medical information and administrative support, including for the first menstrual period to pregnancy, childbirth, infertility, and menopause. The second part would be for recording one’s own information.

People’s average life expectancy is rising, but the period in which childbirth is possible has not changed. Against this backdrop, it is vital for the government to disseminate knowledge and information in order to protect reproductive rights so that women will not lose their window for pregnancy and childbirth. This does not mean to intervene in issues of pregnancy and childbirth. If young men and women wish to marry and create families, if they wish to continue working while raising their children, it is necessary to resolve the issues that stand in their way. To develop a social and economic environment in which young men and women can choose diverse life courses is what is most required in the government’s measures. I would like to propose to the Task Force for Countermeasures against Declining Birthrate (second period) that the enrichment of comprehensive policies should be the foundation of measures to counter the declining birthrate into the future.

* The information contained herein is current as of September 2013.

* The contents of articles on M’s Opinion are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.