Japan’s population to drop 1 million each year due to natural decrease in 2040-2060s

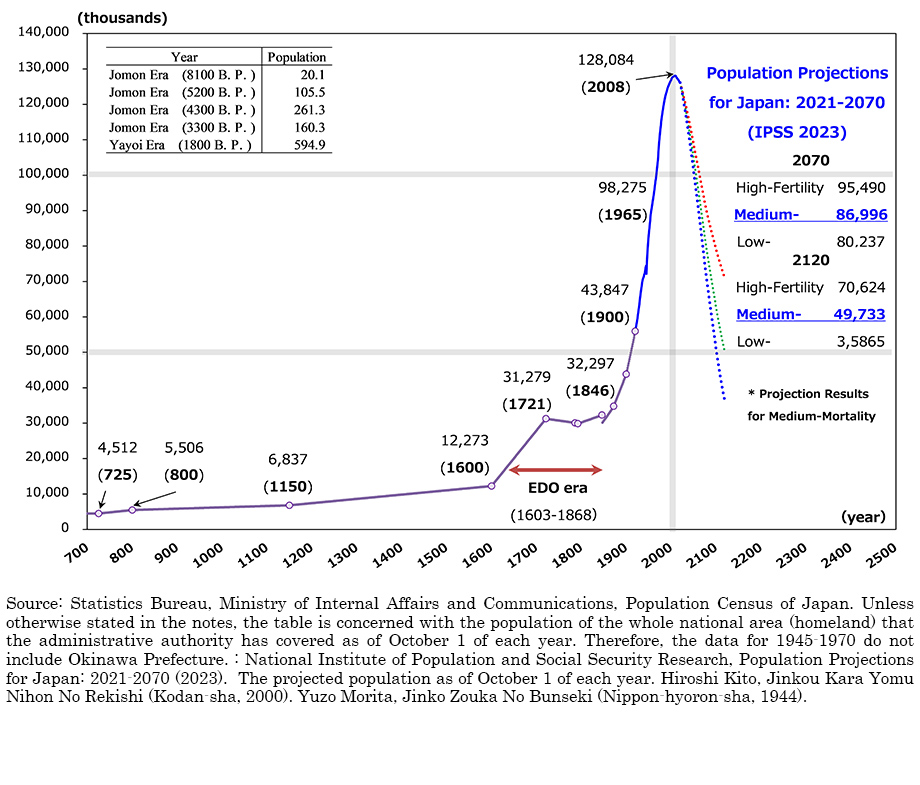

Japan’s population has been on a downward trend since its peak of 128.09 million in 2008. Reflecting on this trend, we can observe a long-term shift known as “demographic transition,” which progresses through phases of high birth and high death rates, high birth and low death rates, low birth and low death rates, and low birth and high death rates.

The era of high birth and high death rates that persisted throughout much of human history transitioned to a phase of high birth and low death rates following the Industrial Revolution, influenced by advances in medical technology and improvements in nutritional standards. A particularly notable example was the dramatic improvement in infant and child mortality rates. Previously, even if five children were born, only two to three would survive to adulthood. However, with such advancements, the majority of children began to survive. As industrial structures transformed, and work arrangements that did not rely on child labor became prevalent, societies moved towards a phase of low birth and low death rates.

“Declining birthrate” means a phenomenon where the birthrate continues to fall below the replacement level, causing the population to decrease. The replacement level is approximately a total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1, which is derived from the sum of age-specific birthrates for women aged 15-49. The TFR represents the number of children a woman would have in her lifetime at these age-specific birthrates.

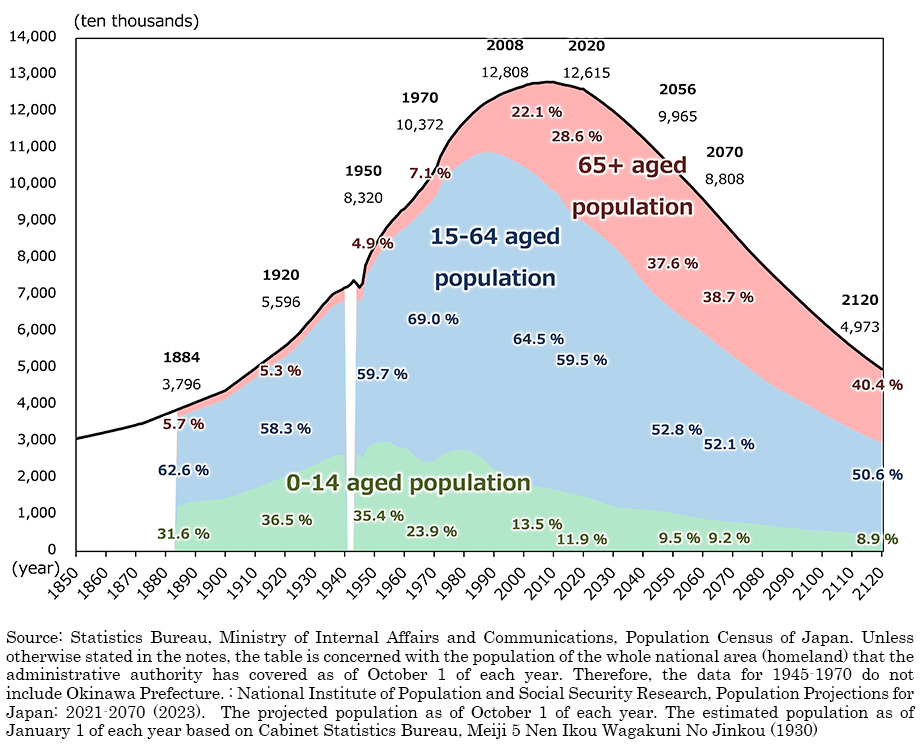

In Japan, the era of high birth and high death rates began around 1870, and the TFR, which was from 4 to 5 before and after World War II, declined to 2 around 1960. After the Second Baby Boom, in 1974, the TFR eventually fell below the replacement level, marking the beginning of a prolonged period of declining birthrates. As a consequence, Japan’s population structure has aged, and since 2007, natural decrease, where the number of deaths among the elderly exceeds the number of births, has structurally led to a depopulating society.

The current era witnesses the aging of a generation born during the period of high birth and low death rates, contributing to the acceleration of population aging. Additionally, advancements in healthcare and public health propelled us into an era where approximately 90% of the population can reach the age of 65, or live to a great age. As a result, the proportion of the population aged 65 and above, which was less than 5% in 1950, has risen to over 28%, and this proportion is expected to increase even further in the future. According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research’s Population Projections for Japan (2023 revision), due to the trend of low birth and high death rates, the population will naturally decline (births < deaths) by one million people annually in the 2040s to 2060s.

In addition to the natural increase or decrease represented by the difference between the number of births and the number of deaths, the social increase or decrease caused by population movement is also a crucial factor for demographic change. Factors contributing to the social increase or decrease in and after 1990 include the amendment to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (1989), which allows employment for individuals of Japanese descent up to the third generation, and the introduction of the Technical Intern Training Program (1993). As a result, the net migration of foreign nationals, calculated by subtracting the number of emigrants from the number of immigrants, has generally shown an increasing trend. Although there was a temporary decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the net migration recovered and increased to 175,000 individuals in 2022. However, many of the recent immigrants, such as technical intern trainees and international students, belong to a younger age group and return to their home countries after a relatively short stay. Consequently, there is a low probability that the growing foreign population will directly contribute to the future demographic stock of Japan.

Unmarried, later marriage for major factor to declining birthrate in Japan’s social structure

Why is Japan experiencing a declining birthrate today? The primary factor is the tendency to stay unmarried and to marry later.

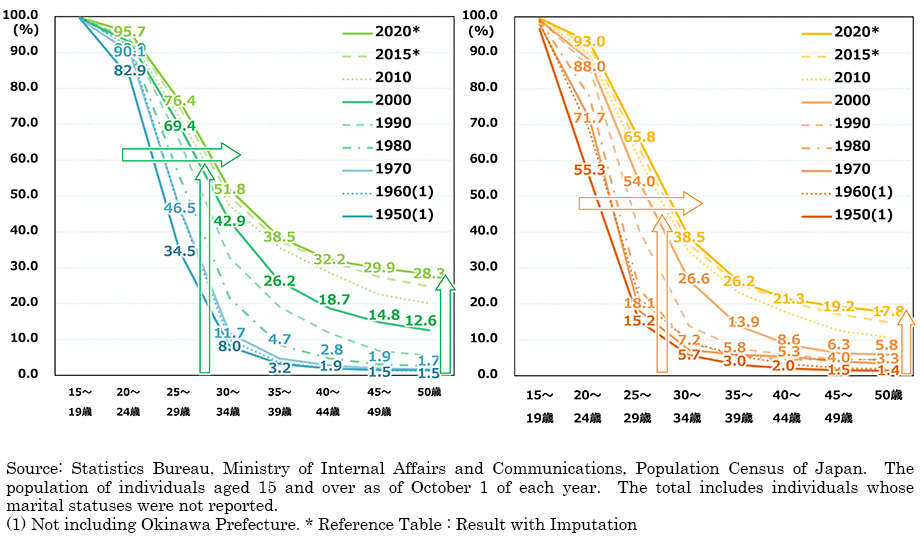

The unmarried rate among individuals in their 20s to 30s has been increasing, and as of 2020, the unmarried rate at the age of 50 is high, with 28.3% for men and 17.8% for women. Since 2005, the impact of the tendency to marry later for complete fertility, has also been significant. The proportion of married couples at complete fertility level with zero to one child has increased, while those with three or more children have decreased, contributing to a decline in the overall birthrate. The average age of first marriage for women, which was 24.2 years in 1970, has risen by over five years to 29.4 years in 2020. The final number of family size for couples marrying for the first time is also affected. While those marrying in their 20s have around two children, those marrying at the age of 30 have an average of about 1.5 children. It is believed that the choice of a child-free lifestyle has increased, but there are also cases where couples desire children but are unable to conceive. The number of births through assisted reproductive technology (ART), accounting for a little under 10% of total births, has reached approximately 64,000 annually as of 2021 (Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Clinical Performance of In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer in 2021”).

Why, then, is the tendency to stay unmarried and to marry later advancing?

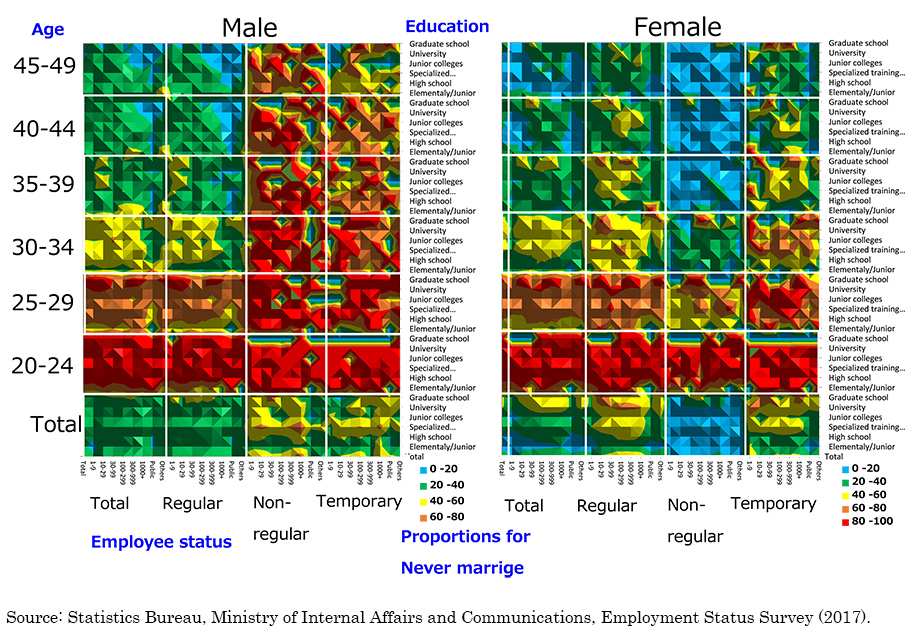

Examining the distribution of unmarried rates in Japan, particularly among those aged 30 and above, there is an asymmetry, with a high unmarried rate observed among male non-regular workers and among female full-time workers. In the case of men, about 70% of those in regular employment express a desire to marry, while those in non-regular employment show a significantly lower inclination. There is a tendency for this inclination to spike when non-regular workers transition to regular workers. It appears that for men, the desire to marry is less likely to arise until their economic stability is established. This situation suggests that having stable economic prospects is considered a condition for marriage.

High unmarried rate among male non-regular workers and highly educated female full-time workers indicates a gender gap in marriage

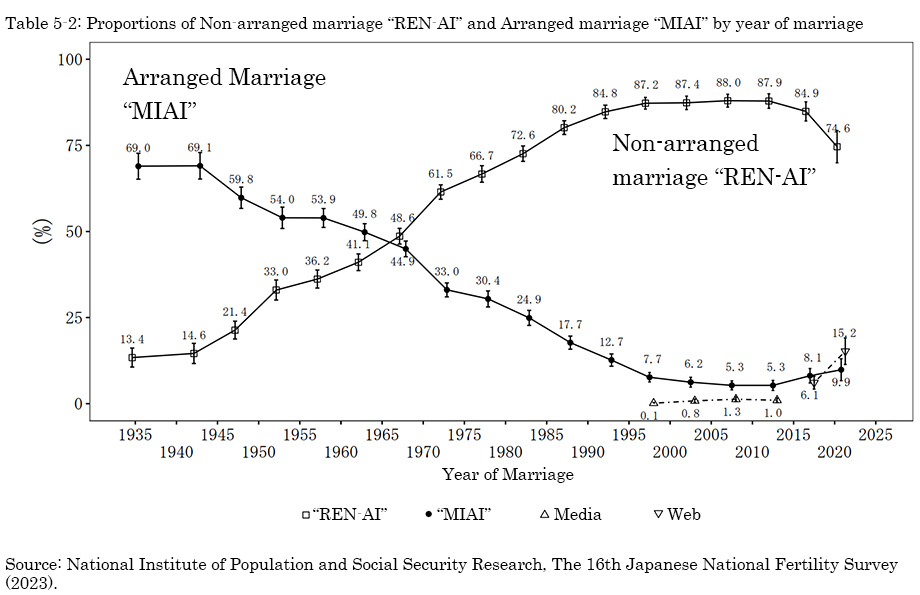

The way people meet and marry has changed significantly. Once predominant, arranged marriages have become rare, and now non-arranged marriages account for around 80-90%. The shift in marriage patterns is believed to contribute to the decline in the number of first marriages, subsequently becoming one of the driving factors for the declining birthrate.

The number of arranged marriages have sharply decreased, but a recent upsurge in meeting through common interests on the Internet is leading to match first marriages

In a 16th National Fertility Survey conducted in 2021 regarding the reasons why unmarried individuals remain single, the most common reason among those aged 25-34 is “not yet met a suitable partner.” Additionally, reasons such as “don’t want to lose the freedom and ease of being single” and “don’t feel the necessity to get married” have increased compared to the past. This situation indicates that unless there is a motivation, such as a desire for children or had a baby, many individuals do not actively choose marriage.

Furthermore, while extramarital births are prevalent in some foreign countries, nearly 98% of children are born to married couples in Japan, according to the vital statistics. Similar trends are observed in some foreign countries like South Korea and Turkey. In contrast, other countries have become societies where 30-70% of individuals have children without getting married. It is said that the number of extramarital children is low in Japan because there is a cultural emphasis on the historical significance, such as taking over the family estate, and societal expectations associated with marriage, beyond just living together with a partner. In addition, the lack of opportunities to meet potential marriage partners and the challenging economic environment surrounding young people contribute to the rising tendency to stay unmarried and to marry later.

Population decline due to natural decrease cannot be immediately halted

In response to the situation of declining birthrates, the Japanese government has implemented measures since the 1990s, including expanding childcare services and promoting a gender-equal society. However, these efforts yielded limited results, and the TFR dropped to a historic low of 1.26 in 2005. Since the measures taken were not directly aimed at encouraging marriage or childbirth, their impact on curbing the trend of declining birthrates may have been limited. Moreover, initiatives directly intervening in marriage or fertility have been avoided, particularly in advanced industrial countries, since the International Conference on Population and Development, commonly known as the “Cairo Conference,” in 1994. At the conference, an international consensus was built for the “reproductive health and rights,” which recognize women’s right to autonomous decision-making regarding their health and reproduction.

In the past, a “marriage-oriented” society was realized through methods such as arranged marriages and encounters through work relationships facilitated by relatives or superiors. However, nowadays, making statements that encourage marriage in a workplace can be problematic, and people are increasingly avoiding community ties, such as introductions by relatives, choosing to move to urban areas for living. Both the state and local governments must confront and address the challenge of maintaining sustainable local communities amid shrinking population, while respecting diverse values and behaviors.

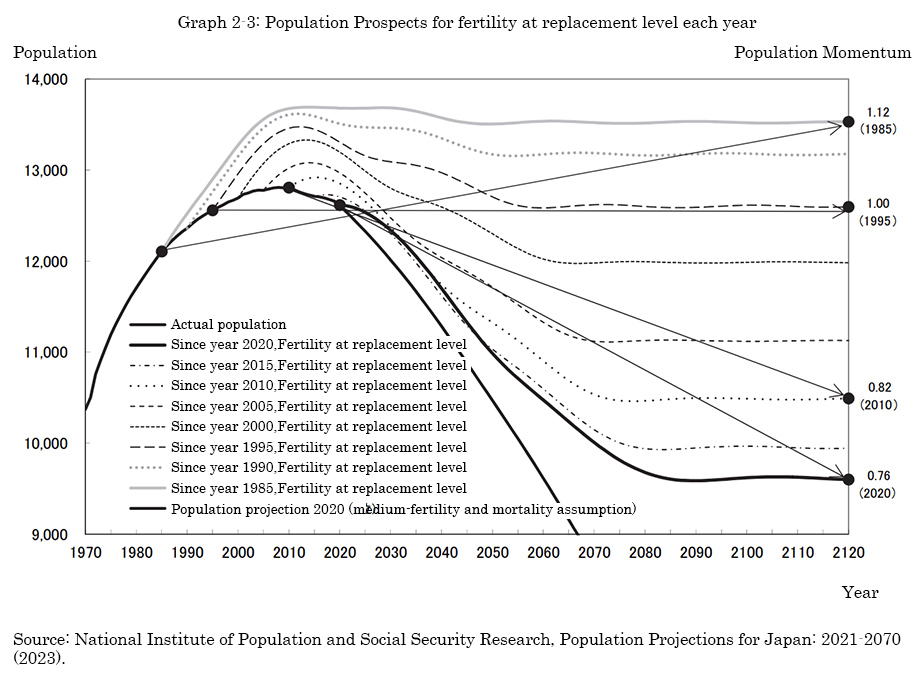

Additionally, even if the fertility rate reaches replacement level, the population decline will not immediately cease.

Population structure exhibits long-term inertia, and even if the birthrate were to increase rapidly, it would take some time for the population of women in the childbearing age range to grow. Without an increase in this population, birthrates will not rise sufficiently. Therefore, a population decline due to natural decrease cannot be immediately halted. According to a report on Population Projections for Japan released at the end of August this year, even if the birthrate reaches the replacement level by 2020, the population decline will continue until 2080-2090 (assuming a constant death rate and zero international population movement). It is estimated that, by that point, Japan’s population will have decreased by about 24% from the current level, accompanied by an aging population.

The current low birthrate, while influenced by societal changes, is also a result of the choices made by each individual. Since the population decline continues even if the declining birthrate is resolved, measures based on the assumption of population decline are essential. The government has already initiated discussions on sustainable social security policies targeting all generations, the development of comprehensive regional care systems, and the “compact city plus network.” The challenge now is how efficiently we can address the issue of population decline.

* The information contained herein is current as of December 2023.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.