The unstoppable declining birthrate in Japan and China; each country’s social circumstances

My specialization, family sociology, is an academic field that examines the relationship between family and society. At present, I am mainly studying the structure and characteristics of Chinese families, and also conducting research with a view of comparing them with Japanese families.

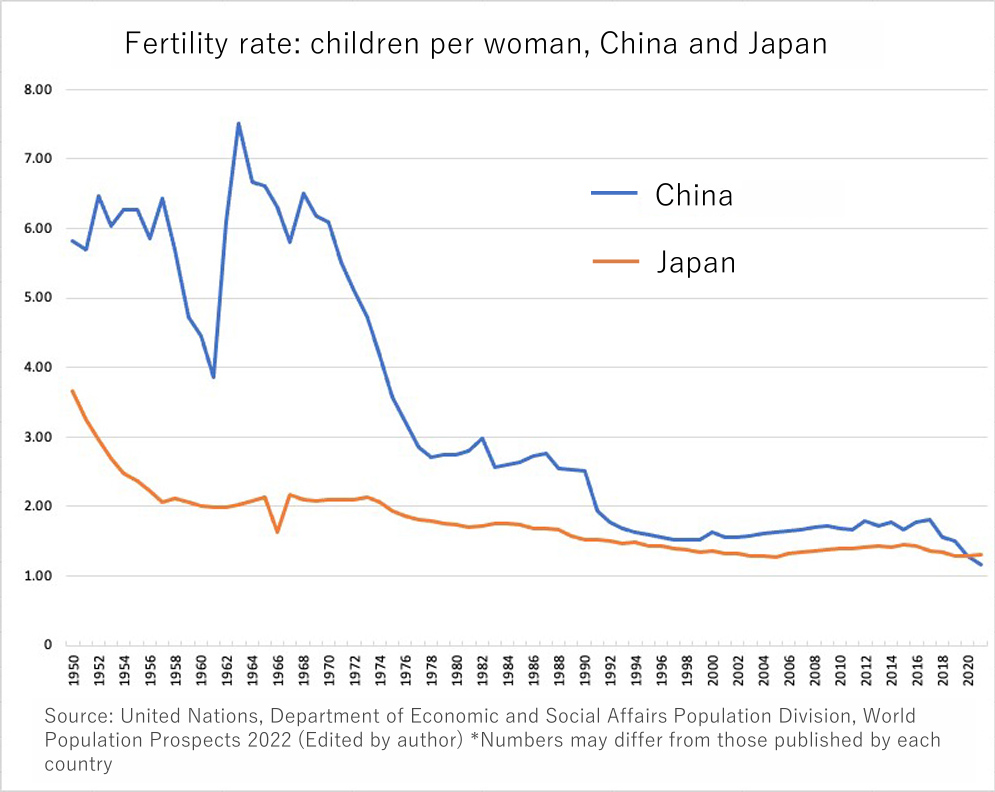

As is well known, today’s Japanese society is an aging society with a low birthrate, and the shift to late marriage, unmarried status, and non-marriage is progressing. On the other hand, in neighboring China, the one-child policy introduced in 1979 led to a declining birthrate, and the population began to decline in 2022. In 2023, it was overtaken by India in terms of total population.

Although both Japan and China are experiencing the same dramatic decline in birthrate, the attitudes toward marriage and childbirth in their respective societies differ in many respects.

According to statistical data, Japanese people are not necessarily negative about marriage and having children. More than 80% of unmarried 18 to 34-year-olds still plan to get married eventually. According to couples whose wives were younger than 50 and who had been married for the first time, “the average ideal number of children” was 2.25, and “the average number of expected children” was 2.01 (*1), when they were asked how many children they planned to have in total.

Since the total fertility rate, which indicates the number of children a woman is expected to have in her lifetime, is 1.26 (2022), it can be said that there is a considerable number of people who do not have children because they are not married and couples who want the ideal number of children but cannot have them in reality.

The primary reason for this is economic factors, but also the fact that women are not able to balance work and family life owing to the disproportionate responsibility for housework and childcare arising from marriage and childbirth, and that public support is insufficient. In addition, owing to the influence of neoliberalism since the 1990s, marriage has become a choice based on the individual’s own free will, and whether one gets married or not has become the individual’s self- responsibility. This is also considered to be one of the causes of late marriage and non-marriage.

In the meantime, looking at China, some surveys point out that the one-child generation in their twenties to early forties who grew up under the one-child policy actually do not want to get married because it is too much trouble. Various conjectures are made for the background to this situation. These include not only rising real estate prices, which are barriers to buying a home, women’s social advancement and changes in urban lifestyles, but also cultural factors such as strong pressure from relatives and colleagues who intervene in marriages.

It is true that Chinese society has stronger marriage norms than Japanese society, and it is considered that marriage is a rite of passage to adulthood and a human responsibility.

According to Chinese researchers who compared the age at first marriage and the lifetime non-marriage rate between 1990 and 2020, the age at first marriage for both men and women has risen significantly over the past 30 years, although the lifetime non-marriage rate has not changed much. In 2020, the lifetime non-marriage rate in China was 0.4% for women and 3.1% for men. It remains a marriage-oriented society (*2).

Even in today’s Chinese society, it is believed that not having children is the greatest form of unfilial behavior. Thus, the parents’ generation, who believes that it is the parents’ responsibility to let their children get married and leave behind offspring, do whatever they can to encourage their children to get married. In fact, parents are actively involved in the selection of spouses for their children by, for example, engaging in spouse hunting on behalf of their children and registering their children’s information on dating apps.

*1 National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, “The 16th Japanese National Fertility Survey (National survey on marriage and childbirth)” (Conducted in June 2021)

*2 Chen Wei, Zhang Fengfei “Marriage Delay in China: Trends and Patterns” (Population Research Vol. 46, Issue (4), Renmin University of China, 2022)

Battle between families over the childbirth of “only daughters” who appeared in large numbers under the one-child policy

As mentioned earlier, China implemented the one-child policy for 35 years from 1979 to 2015 to control its huge population, limiting the number of children a couple can have to 1 in urban areas and 1.5 in rural areas. This led to the emergence of the one-child generation.

In 2016, China abolished the one-child policy and introduced the two-child policy, citing labor shortages and an increase in the number of elderly people requiring support and nursing care. Furthermore, in 2021, the policy was changed to allow the birth of a third child. However, despite the increase in the number of children they can have, the annual birth rate has not increased as much as the Chinese government expected.

In fact, the number of births has been falling since 2017. According to the announcement of the Chinese government, the number of births was 9.02 million in 2023, which was as many as 540,000 less than the previous year. According to government estimates reported in Chinese media, the total fertility rate (the number of children a woman gives birth to in her lifetime) in 2022 was 1.09, lower than Japan’s 1.26.

Many of the reasons for the decline in the number of births are similar to those in Japan, such as the heavy educational and economic burden and the disproportionate burden of childcare on women. On the other hand, a phenomenon rarely seen in Japan with regard to childbirth by the child generation is the request for childbirth (childbirth prompting) by the parents.

Childbirth prompting is a behavior which parents of the one-child generation ask their married sons and daughters to give birth to a second or third child, being triggered by the policy changes. What is notable here is intergenerational negotiations between parents and children, or between parents on the wife’s side and parents on the husband’s side, regarding the childbirth of the only daughter from the one-child generation.

In the first place, in many Chinese households, parents live with their children (especially their sons) after they get married, and assist them financially and support raising their grandchildren. Even after China has achieved economic development, it cannot be said that social welfare is sufficiently developed, and the government expects mutual support within families.

The reason why parents provide childcare support for their children is that, from the children’s point of view, they have no choice but to ask parents, relatives, babysitters, etc. for childcare cooperation owing to the lack of social childcare resources. From the parents’ point of view, the childcare support they provide to their children is greatly related to their own welfare in old age. As public resources such as support and nursing care are also limited, they have to rely on their children (especially their sons) to support them in old age.

China, having a Confucian culture, continues to be a male-dominated society, and a marriage where the bride moves into the groom’s household is a typical form of marriage. Thus, a woman usually marries into her husband’s family and lives with the husband’s parents after marriage. In urban areas, only daughters tend to be raised with exclusive parental love, resources, and educational investment. However, since there are no male siblings in the family, when an only daughter marries into her husband’s family, her parents lose their welfare supporter in old age.

How do Chinese “only daughters” deal with marriage and childbirth?

In response to the government’s demographic policy shift since 2016, which has increased the number of children that people can give birth to, parents of only daughters are now pursuing strategies such as asking their daughters to give birth to multiple children (childbirth prompting) and making the children (grandchildren) inheritors in the family line.

In fact, my on-site and remote interviews conducted in Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province, China, from 2019 to 2023 revealed some aspects of the negotiations between parents and children and between parents on the wife’s side and parents on the husband’s side.

The survey covered 40 only daughters born and married under the one-child policy in urban areas. First of all, most of the 40 only daughters who had or were expecting a second child were requested to have a second child by their parents. Moreover, since almost all first-born children assumed the surname of the husband and belonged to the husband’s side, I could tell that there was little room for negotiation between the husband’s parents and the wife’s parents regarding the first-born child.

In this situation, the relationship between husbands’ parents and wives’ parents was not so much that they competed to secure inheritors, but rather that the husbands’ parents were responsible for a large amount of the wedding expenses and provided housing, while the wives’ parents were playing a supporting role, such as providing electric appliances and cars, and the husbands’ parents maintained their superiority in securing inheritors while accepting some of the wives’ parents’ needs.

In fact, there were quite a few cases where the parents signed a prenuptial agreement concerning the second child and agreed that the child would take the surname of the wife and become a descendant of the wife’s family. In some cases, if the first child is a girl and the second child is a boy, the boy takes the husband’s surname and the girl changes her surname from the husband’s to the wife’s.

From this, we can confirm that the traditional Chinese patrilineal kinship norm is being preserved, by which they never infringe on the husband’s interests, although the wife’s parents can negotiate to secure an inheritor in their family line.

In any case, from the perspective of modern Japanese people, they may have a certain feeling of hesitation in Chinese society, where parents strongly intervene in marriage and childbirth. Also, the patrilineal kinship norm that values the male child in the family may feel out of place in this day and age.

However, I would like to point out that Japan, like China, belongs to the Confucian cultural sphere, and that male-dominated values remain deeply rooted. For example, in Japan, there is a system of choosing the family name after marriage between the wife and the husband. However, indeed about 95% of them are choosing the husband’s family name and wives are changing their family name. From the perspective of countries and regions where selective separate surnames are institutionalized, it may look like a very male-dominated country with a strong patrilineal norm.

In both countries, where the birthrate is declining, there are similarities as well as contrasts in their cultures and societies. In Japan, there is little interference but also little support from parents. Society has a sense of values that people themselves should find a marriage partner on their own responsibility and the couple should raise their children by themselves (mostly by the wife). In China, on the other hand, parents are in charge of their children’s spouse hunting, and even after marriage, they actively support their children in financial and child-rearing matters, but they also interfere in various matters, such as the number of childbirths and the family names of their children (grandchildren).

One is a society with freedom but has little support from relatives for marriage and childbirth, and the other is a society with great support from relatives for marriage and childbirth although it has less freedom. Of course, the lack of public support is common in all societies. Which society do you feel is agreeable?

By comparing seemingly similar issues from the inner perspective of different societies, you also deepen your awareness of the society you belong to.

* The information contained herein is current as of August 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.