Japan is blessed with floriculture and its genetic resources due to diverse nature and Japanese sensibility

Kaki (花卉: ornamental plants) represents all plants that are appreciated by humans. Ornamental plants include not only flowers but also foliage plants and trees of which the leaves and branches are appreciated, as well as ferns and mosses. Moreover, floricultural genetic resources include not only wild plants that grow naturally in the fields but also horticultural varieties that are selected and improved (bred) by humans.

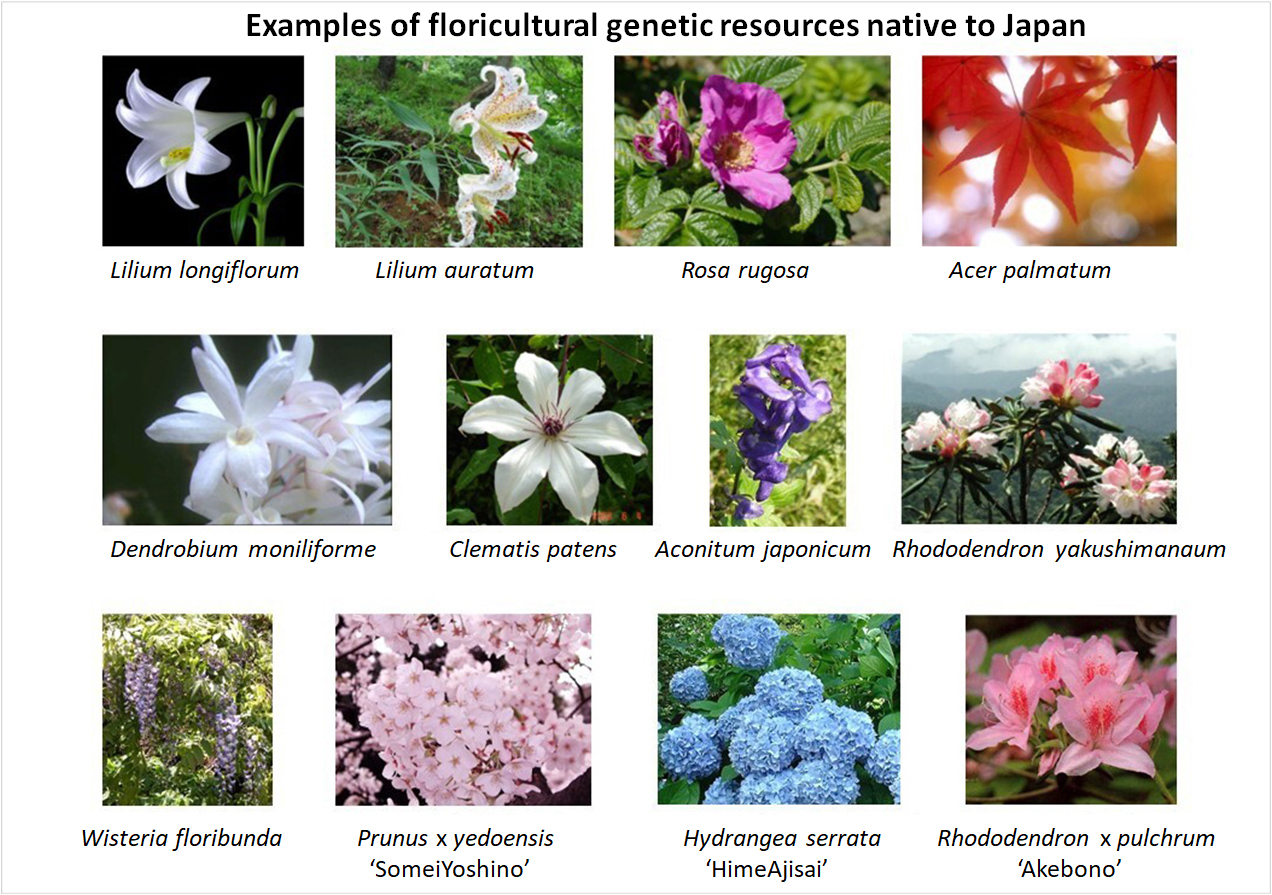

Japan is a country miraculously blessed with floricultural genetic resources with high ornamental value. Azalea (躑躅), hydrangea (紫陽花), camellia (椿), wisteria (藤), cherry blossom (桜), maple (紅葉), lily (百合), iris (花菖蒲), primula (桜草), etc. are ornamental plants that were cultivated as horticultural varieties from wild plants originally growing naturally in Japan’s natural habitats. (Note: kanji 漢字notation is also used here as part of Japan’s floriculture.) On the other hand, chrysanthemum (菊), Japanese apricot (梅), tree peony (牡丹), herbaceous peony (芍薬), morning glory (朝顔), etc. were brought from China and Korea in old times together with Buddhism as medicinal plants. After that, in Japan, they were bred in their own way to appreciate the beauty of the flowers, and many varieties were generated. Moreover, although pansy, carnation, cosmos (秋桜), petunia, etc. are native to the Mediterranean region and Latin America, their revolutionary varieties were bred in Japan. In recent years, lisianthus, or Eustoma, which is native to North America, and only used to have types with a small purple flower with a single petal, has been significantly modified in Japan. Now it has become a variety with large double petals and various colors that looks like a rose or peony, and they are now displayed in flower shops around the world.

Forces of both nature and humans caused the blessing of floricultural genetic resources and the development of floriculture in Japan.

We firstly point out that a factor causing the diversity of various wild plants in Japan is the geographical position of the Japanese archipelago. The Japanese archipelago is located in the east of Eurasia continent, which is in the mid-latitude of the Northern hemisphere, and secluded by sea in all directions. It has four distinct seasons with significant differences in temperature, precipitation, and day length. This dynamic change is a factor in the growth of plants with habitats that suit seasonal changes. Moreover, the Japanese archipelago is long from north to south and consists of temperate, subarctic and subtropical zones. It also has differences in altitude from coastal areas to precipitous mountainous areas, and significant climate differences between the Sea of Japan side and the Pacific side divided by these mountain ranges. Ancestral plant species that reached the Japanese archipelago from the continent and oceanic islands tens of thousands of years ago generated many endemics by adapting themselves to these diverse natural environments and changing their forms and nature one after another. Thirty-six areas in the world where biodiversity is remarkable are certified as “biodiversity hotspots.” The Japanese archipelago is one of them, and only with vascular plants, more than 2,500 of endemic species (including subspecies and taxonomic variants) are identified.

Development of floriculture is also influenced by Japan’s agricultural background. For example, concerning the cultivation of rice, which is the staple food, blooming of cherry blossoms was used as a criterion to prepare for nursery beds and planting. Also, seasonal changes in plants and human activity were closely related. In Japan, where there are dynamic differences in the natural environment between areas and changes in plants that we can see in different seasons even in the same place, there has been a culture from old times to notice and appreciate the seasonal changes in plants in fields and gardens, as is written in the Manyoshu (万葉集) and Kokinwakashu (古今和歌集) poem collections. Japan has refined its original gardening culture such as ikebana (生け花: flower arrangement), bonsai (盆栽), and Japanese gardens, to enjoy nature and the season itself in everyday life. Moreover, as mentioned before, plants that came into Japan as medicinal plants were developed into many varieties by Japanese sensibility through their liking to enjoy the beauty of those flowers.

Japan’s horticultural plants became widely known abroad because of P.F.B. von Siebold, a German who visited Japan during the Edo period. Japan at that time was secluded from other countries. However, Siebold, who was a physician at the Dutch trading post, was allowed to open a school to teach medicine and natural science at Narutaki, Nagasaki. In the meantime, he had a mission to conduct research on Japan’s natural history and folklore, and to reconsider trade between Japan and the Netherlands. Thus, he ordered students, who came to study from different parts of Japan, to collect plants. Based on a vast amount of Japanese plant specimens that were collected as such, he later wrote Flora Japonica, and also established a botanical garden in Leiden, the Netherlands, to habituate plants that were transported from Japan. Furthermore, he set up the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Horticulture in the Netherlands and sold Japanese-native horticultural plants by mail-order, triggering a big boom in Japanese horticultural plants in Europe. In the botanical garden of Leiden University in the Netherlands, plants that were brought back by Siebold then still alive today. After Siebold, many plant hunters from different countries visited Japan in search for Japanese plants, and many Japanese floricultural varieties travelled to Europe. After opening up the country after the Meiji Restoration, there was a time when Japanese floricultural plants, including lily bulbs, became a big export industry.

International Horticultural Expo 2027, Yokohama, Japan

Biological Properties of Biodiversity Hotspots in Japan (National Museum of Nature and Science)

Flora Japonica (Kyoto University Rare Materials Digital Archive)

Japanese floricultural varieties and floriculture developed in the Edo period and spread to different places

It was during the Edo period (1603-1867) when the horticultural varieties and floriculture rapidly developed in Japan. During this period, a stable political administration continued, people could spend their lives peacefully, and thus various cultures matured. Policymakers of the Edo shogunate government had an accommodating view toward floriculture, advancing a policy to promote it. Moreover, under the sankinkotai (参勤交代) regime, the daimyo’s mansion and samurai’s residence, where major daimyo (大名: provincial lords) and samurai nationwide regularly stayed by turns, were located in Edo (currently, Tokyo City). Ornamental plants with high aesthetic value that were brought from their hometowns were planted in their gardens of Edo, enabling Edo to establish the foundation for collecting ornamental plants from all over Japan. At Rikugien and Shinjuku Gyoen in Tokyo City, we can still see a horticultural variety of azalea called Edo-Kirishima (江戸霧島), which was very popular variety at that time, derived from the Kirishima Mountain Range in Kyushu and planted there in the Edo period. It is considered that the gardeners who took care of these daimyo mansion gardens took over and circulated some of them. In Somei, Kamikomagome village (currently, Komagome, Toshima-ku) of Edo, there was the world’s biggest garden center, known as gardener street, where anyone could purchase ornamental plants. Then, plants with aesthetic value that were obtained in Edo were brought back to people’s hometown and various horticultural varieties were spread all over Japan. For example, the famous hydrangea which Siebold named Hydrangea otaksa after his beloved Japanese wife Taki, is also thought to have been named without him knowing that it was a temari (手毬: handball) or mophead-type variety generated from lace cap-type wild hydrangea that had already spread as far as Nagasaki from Edo by that time. Moreover, Shigekata Hosokawa, the 6th daimyo of Higo (currently, Kumamoto prefecture), encouraged his subordinates to pursue floriculture for their mental training, which led to the cultivation of many ornamental plants. Later, six types of flowers were selected as the “six flowers of Higo.” Among them, iris is thought to have originated from the varieties created in Edo.

Hanami (花見: custom of cherry blossom viewing) also matured during the Edo period. Measures to create a sight of cherry blossoms in Edo started by Yoshimune, the 8th shogun of the Tokugawa family, and wild cherry blossom trees from Mt. Yoshino in Nara were planted at sites, including Gotenyama and along the Sumida River. A horticultural variety of cherry blossom named ‘Somei-Yoshino’ (染井吉野) is a variety accidentally generated in Somei of Edo in the Edo period. It was named as such because the beauty is comparable to the cherry blossoms of Yoshino. Scientifically, it is verified as a hybrid of Prusus pendula and P. lannesiana. This ‘Somei-Yoshino’ hardly bears seeds. However, owing to its high aesthetic value and ease of propagation by cutting and grafting, its vegetative propagated clones quickly spread nationwide, generating cherry blossom sights in many parts of Japan. Moreover, we can tell from ukiyo-e (浮世絵: Japanese woodblock prints), etc. that iris and primrose were also objects of blossom viewing at that time.

Closure of the country during the Edo period also played a role in creating an environment that encouraged generating unique floricultural varieties that originated in Japan. For a long period, as a result of pursuing something more sophisticated and different using the limited floricultural genetic resources, for chrysanthemum and morning glory, varieties that are unable to survive in nature were created, with extreme modified flower-shape variants which could not bear seeds. Moreover, varieties that show a phenomenon called variegation, in which leaves acquire patterns of white or yellow stripes or dots because of partial failure to create chlorophyll due to mutation, etc., were found in various plants. Thus, Japan’s unique floriculture to value these plants as odd items was also generated.

During the closure of the country at that time, information on natural science that was discovered in Europe was limited. Therefore, genetic knowledge such as pollens having a genetic factor was unknown to the general public. Many of the enormous number of varieties of floricultural plants that were generated in the Edo period are thought to consist of a selection of good ones that are accidentally found among seedlings derived from naturally generated mutations or chance seedlings that are created by natural crossing by wind, vibration, insects, etc., instead of artificial hybridization by humans.

In my laboratory, in order to clarify the current status of Japan’s floricultural genetic resources and contribute to continuity toward the future by conservation and the use for breeding, we have conducted research on diversity and evolution of wild populations and the process of establishing horticultural varieties, by investigating forms and the biology of currently existing wild populations in their natural habitat, analysis using DNA markers and analyzing the components. So far, azalea, lily, iris, and hydrangea have been investigated. Concerning azalea, we suggested the possibility that the Rhododendron transiens, of which this variety was developed during the Edo period, was generated by natural crossing between a horticultural variety such as Hirado azalea generated in western Japan and R. kaempferi, which grows naturally in satoyama (里山: undeveloped woodland near a village) in the Kanto region. In the joint research with researchers from Italy and Belgium, we clarified that the variety called Belgian azalea, which is distributed worldwide as a potted azalea, was established based on a Japanese horticultural variety that was created since the Edo period. Concerning the lily, as for Lilium auratum var. platyphyllum, an endemic to the Izu Islands which blooms the world’s largest flower as wild lily, we clarified the diversity by the islands, and its relation to L. auratum, a closely related species that grows naturally on the Izu Peninsula. We also clarified that a beautiful lily called Izu-yuri, which grows naturally on the Izu Peninsula, is a hybrid generated by natural crossing between L. japonicum and L. auratum, and has various forms. Concerning iris, in the joint research with Tamagawa University, we estimated the regional groupings of Iris ensata var. spontanea, the wild species which became an origin of horticultural varieties Hanashobu (花菖蒲) that were cultivated in the Edo period. Currently we are conducting research on hydrangea, including H. macrophylla, H. serrata var. serrata, and H. serrata var. yesoensis, the wild varieties that became origins of horticultural varieties of hydrangea, concerning their genetic diversity of the wild population in its native habitat, the relation between the old horticultural variety that has been exported to Europe since the Edo period and the wild population in Japan, the strong environmental stress resistance (especially, salt tolerance) of H. macrophylla, etc. In addition, mutant morning glory, a morphological variation cultivar group established since the Edo period which could not bear seeds, and thus it needs lots of work to maintain the parental lines possessing recessive phenotype and select mutant individuals after crossing. Therefore, we are trying to establish the clonal propagation using the tissue culture system.

<National Diet Library, Japan “Cherry blossom viewing spots”>

Floricultural genetic resources are difficult to reproduce once they are lost

As I mentioned, Japan’s floricultural genetic resources are precious also from the global perspective. However, currently, it continues to be difficult to conserve and maintain both wild populations in Japan and horticultural varieties that were created in the past. We confirmed that there were wild populations that could only be observed in extremely limited areas, and some old horticultural varieties created in the Edo period only had inherited genes that were already lost in the current wild populations.

In the wild populations, decreased numbers of individuals and the disappearance of populations due to change of the natural environment, artificial development and illegal smuggling are observed. Botanical gardens are important for ex situ conservation. However, owing to a decrease in budget and manpower, their downsizing, their management being shifted to the private sector, and their discontinuation are increasing. Moreover, as for private organizations and individuals who inherited the unique varieties which were created in the Edo period, continuation is endangered owing to aging of persons, and there is a risk that hundreds of varieties will be lost at once if one person passes away. Once we lose such unique varieties, it requires lots of energy and time to reproduce them, and we will never be able to see them again.

Concerning some floricultural genetic resources, public efforts for conservation are ongoing. The Gene Bank Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries conserves breeding lines and horticultural varieties of chrysanthemum, carnation, etc., which are important for agriculture. In the National Bio-Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, mutant morning glory was selected as one of the research materials of biology, and it is conserved and distributed, having Kyushu University as a representative institution. Furthermore, concerning primula, the National Museum of Japanese History and the National Museum of Nature and Science, in cooperation with the University of Tsukuba and private organizations there, are engaged in an educational campaign to conserve the varieties from the Edo period. However, these are merely a small part of the enormous amount of Japan’s unique floricultural genetic resources.

In such a situation, the Japan Association of Botanical Gardens (JABG), which is coordinating botanical gardens in Japan, started the Plant Conservation Center Network Project in 2006 with the aim of ex situ conservation of Japanese-native endangered plants. In addition, learning from the system of the U.K., which is a leading gardening country, in 2017, they started the JABG National Plant Collection Certification System, aiming “to protect and pass down precious plants as cultural assets and genetic resources cultivated in Japan to future generations regardless of being wild species or cultivated species,” and certified 17 items by May 2024.

In recent years, the importance of Japan’s floricultural genetic resources and floriculture is being recognized again. Japan’s diverse wild plants and unique floricultural varieties are precious breeding materials. Moreover, artistic dwarf potted trees became common in Europe and the U.S. as BONSAI, and Japan’s bonsai plants and garden trees are being purchased by affluent people from Asia. Japan as a country also recognized the importance of ornamental plants, and by establishing the Ornamental Plants Promotion Act 10 years ago, they developed the legal system to cultivate Japan’s ornamental plant industry and started promotion measures for floriculture such as supplying subsidies for event programs related to ornamental plants. In the future it is hoped that Japan’s floricultural genetic resources and floriculture will be passed on as precious natural and cultural assets and be presented proactively and developed further.

The International Horticultural Expo that will be held in 2027 in Yokohama is a chance to promote the magnificence of Japan’s ornamental plants to the world. Now that inbound tourism is rapidly recovering after the Covid-19 crisis, people visiting Japan from abroad are strongly looking for something that feels Japan, such as Japanese food, landscape, architecture, traditional craftworks, and gardens. Such aesthetic feelings and worldview rooted in Japan’s nature and Japan’s floricultural genetic resources and floriculture are closely related. To take another look at the wild plants generated in Japan’s natural environment and horticultural varieties and gardening culture that were created by Japanese sensibility, and connect it to the preservation and application of floricultural genetic resources and development of floriculture, is not nostalgia for the past, but something very important for future Japan.

National Plant Collection (Japan Association of Botanical Gardens)

The Ornamental Plants Promotion Act ※Japanese text only

* The information contained herein is current as of March 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.