Youth voter turnout needs to be viewed in relative terms, not in absolute terms

We often hear the mass media reporting that “youth voter turnout in Japan is in decline.” In many cases, the term “in decline” is used to indicate that the absolute turnout among young people is decreasing over the years. However, from the perspective of how much young people’s opinions are to be reflected on policy, what matters is the turnout among young voters relative to voters of other age groups. Even when the absolute youth turnout is decreasing, young people’s votes may still have a significant impact on election outcomes if the turnouts among other age groups are also decreasing. Conversely, even when the absolute youth turnout is increasing, youth votes may have less impact on election outcomes if the turnouts among other age groups are increasing even more.

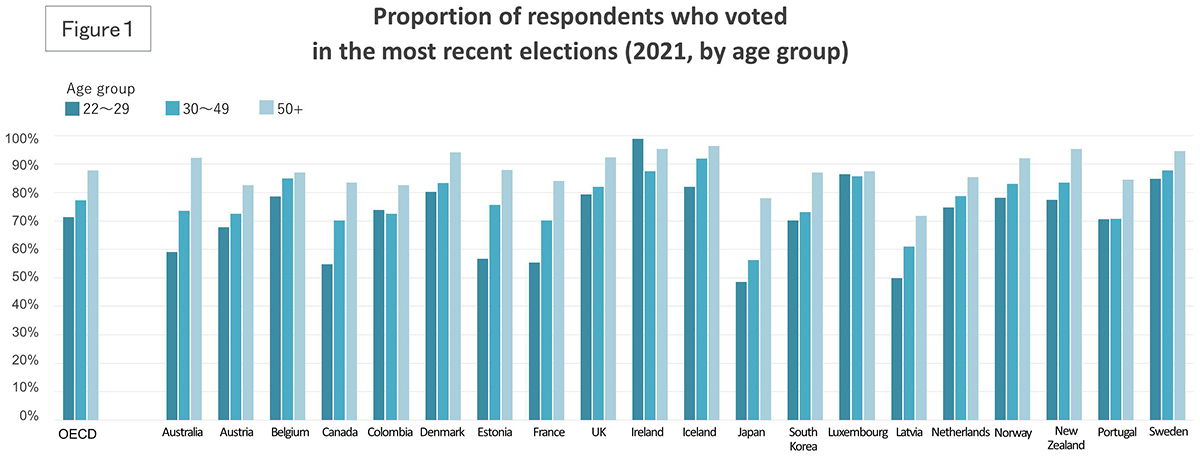

Keeping this in mind, take a look at Figure 1. This figure shows turnouts by age group in the most recent national elections in OECD countries as of 2021. While the displayed numbers may not be accurate because they are calculated based on public opinion polls, we can see that the absolute voter turnout among young people (22-29 years old) is indeed the lowest in Japan among the countries in the figure. Latvia is the only other country where youth turnout is comparable to (but still higher than) that of Japan. If we focus on the difference in the voter turnout between youth and the older generation (over 50 years old), on the other hand, Japan is still one of the countries with the largest gap but Australia, Canada, France, and Estonia also have a comparable size of difference of about 30%. In these countries, the absolute youth turnout is higher than that of Japan, but turnouts among older generations are also higher, so the relative impact of young people is similar to that for Japan.

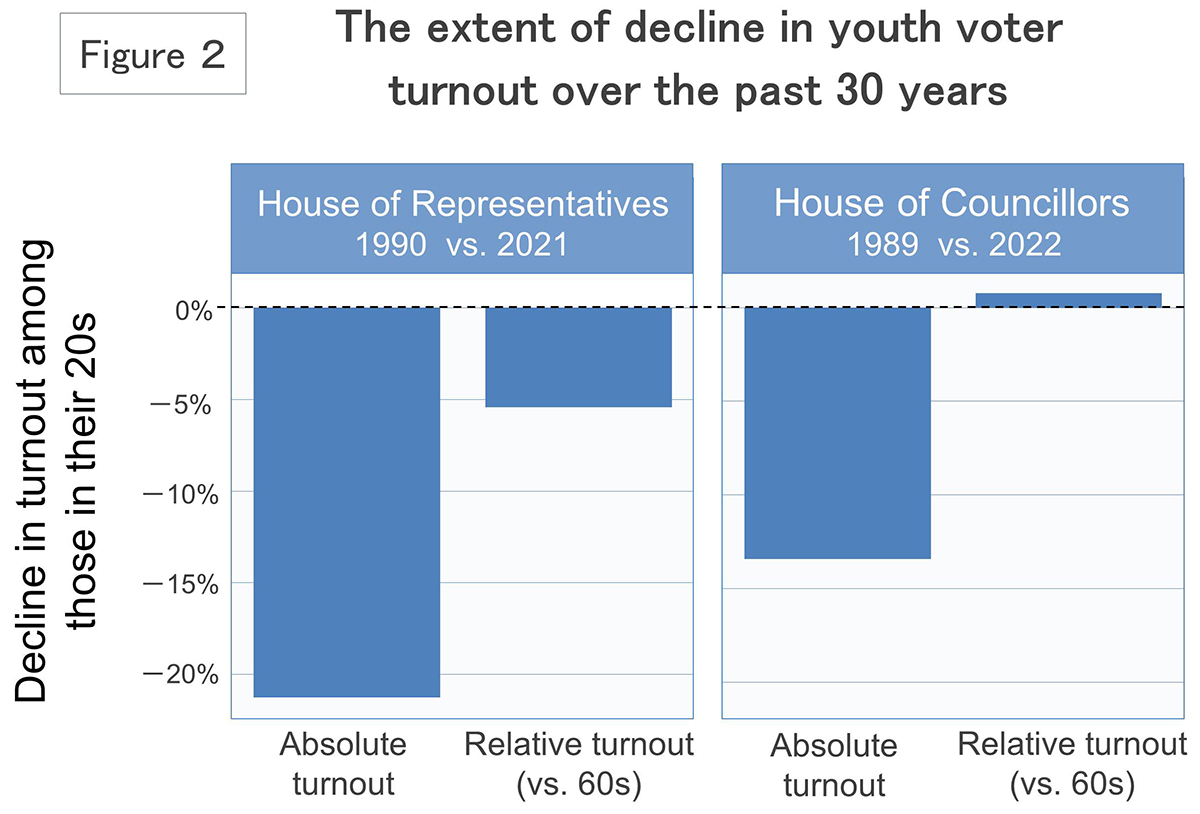

Now, what can we see if we take a chronological look at youth voter turnout? In Japan, it is known that voter turnout has been declining significantly, especially since the mid-90s. What we can look at is the percentage decline in voter turnout among young people (in their 20s) in the national elections of 1989–90 and 2021–22, based on the voter turnout data by age group for House of Representatives and House of Councilors elections, published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Figure 2 shows that the absolute turnout among people in their 20s has significantly decreased over the past 30 years, by just over 20% in the House of Representatives elections and just over 10% in the House of Councilors elections, respectively. Looking at these results alone, it is not hard to see why people summarize the trend by saying “young people nowadays are…”. But what if we evaluate it in terms of the relative turnout rate? Figure 2 generates the relative voter turnout by calculating the gap between the turnouts of people in their 20s compared to people in their 60s, the age group with the highest turnout. The figure then plots how the gap has grown over the last 30 years. It turns out that the decline in relative youth turnouts in the House of Representatives elections was only about 5%, which was only about one-fourth of the decrease in the absolute youth turnouts. The relative youth turnouts in the House of Councilors elections even show a slight increase. In other words, from the perspective of youth’s impact on election results, the relative youth turnout has not declined as dramatically as the absolute youth turnout has in the past 30 years.

Voters who do not know the “right answer” may become a motivating factor for politicians

The premise behind the argument for increasing voter turnout is that voting is beneficial. However, does participating in elections bring benefits to voters themselves and society in the first place? This question is one of my research themes (*1). Let us consider the meaning of voting, assuming that voters in a democracy pursue to “having governments and politicians implement policies that they believe will benefit them.”

If voters know which politician can deliver the policies they want, in other words, if they know who to vote for, participating in elections is easily beneficial. But the reality is that there are a certain number of voters who do not know who to vote for. If those voters vote for the “wrong answer,” that is, politicians who cannot implement the policies they want, politicians who are the “right answer” for them will be less likely to win. In other words, abstaining may yield better results than ignorant voting. Abstaining from voting can also be a reasonable political choice if the abstaining voter is reaching a logical conclusion that relying on others will lead to better policy outcomes.

But you may feel like abstaining is still a next best option. Then, the persisting argument is that it is it ideal for all voters to have a higher level of interest and knowledge in politics so that everyone knows the “right answer” to make votes beneficial for them. There are, however, two logical concerns to this idea.

The first is the cost of reaching the “right answer.” Trying to reach the right answer may not be a costly for those who are already interested in politics and know how to find information, while it may be time-consuming and expensive for those unfamiliar with politics. As mentioned earlier, not all voters need to know the “right answer” to steer elections in the right direction. In fact, if we pressure everyone to come up with the “right answer,” the wellbeing of society as a whole may decline, as some people must pay a significant cost to achieve it. Of course, it would be a problem if no one knew about politics, but a society in which all voters are required to be highly attentive and knowledgeable about politics can also make some unhappy.

The second is the behavioral logic of politicians. It is an extreme case, but suppose that all voters have a high level of interest and knowledge in politics. Also suppose these informed voters can easily assess the abilities of candidates once they are elected, although they cannot judge the abilities of candidates who have never been elected. Consequently, less capable politicians will always be defeated in the second election even if they can be elected once. Then, the optimal solution for politicians with limited abilities who happened to be elected once would be to stop making efforts and just focus on securing financial gain. This is because they would not want to try hard knowing that they will not be elected second time. Conversely, imagine a situation in which voters lack interest and knowledge in politics required to fully assess the capabilities of incumbent politicians. Then, politicians who were elected in spite of their limited competence will have a chance to win an election again. This perception that “working hard may increase the chance of getting re-elected” is a motivating factor, creating an incentive to make efforts and carry out policies that benefit those unfamiliar with politics. In such a case, voters who do not know the “right answer” can be a catalyst for politicians to work harder.

Through above discussion, I have no intention to deny the importance of political knowledge and participation in elections. If voters with a high level of political knowledge and interest participate in elections, they can certainly steer the election in the “right” direction. However, considering costs of accumulating political knowledge and interest, as well as the behavioral logic of some politicians (especially those who are less competent), it is premature to conclude that low political interest, lack of knowledge and voter abstention necessarily have a negative impact on society.

*1 Kato, Gento. 2020. “When Strategic Uninformed Abstention Improves Democratic Accountability” Journal of Theoretical Politics 32(3): 366-388

When voting, there may be a gap between preferences and expectations

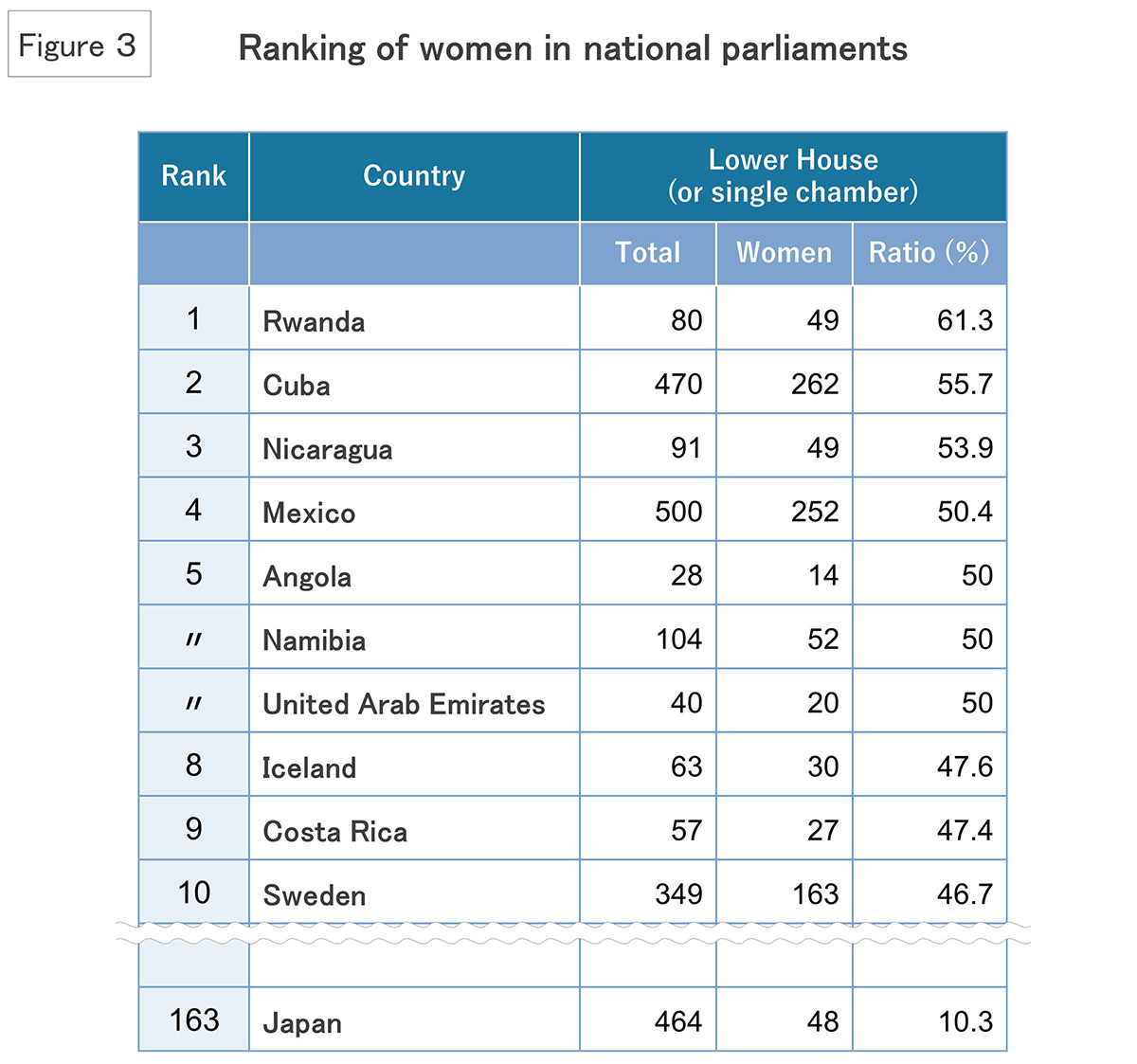

Along with the low voter turnout among young people, the low number of female lawmakers is also an issue related to elections in Japan. The percentage of women in the House of Representatives in Japan (as of 2021) is about 10%, which is one of the lowest in the world. Looking at the ranking of the percentage of female members of parliament (Figure 3), Japan ranks 163rd out of 184 countries with a national parliament, including non-democratic countries. No other developed country, including OECD member countries, has a lower percentage than Japan. Even more, the reality is that the number in Japan is lower than those in some African and the Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, where it is hard to imagine the awareness towards women’s rights is high. From the perspective of gender, it cannot be said that “politics in Japan is representing its voters.”

What is preventing more females enter politics in Japan? This is another question that I have been working on. If we assume that elections are fully democratic, we might be able to say that it is simply because voters value male candidates more than female candidates. Being a woman can be a disadvantage in elections because of the stereotype that “women do not have interest in nor knowledge of politics.” However, research on the relationship between vote choice and the candidate gender in Japan demonstrates that average Japanese voters do not necessarily value female candidates less than male candidates (*2). In fact, there is even a tendency to prefer women to men.

Although there is no consensus among researchers on the main reasons behind the slow increase in the number of female Diet members, recent development in the research indicates challenges in recruiting female candidates. This is critical, because, before winning or losing, no woman can be elected if there is no female candidate running in elections in the first place. For example, it is argued that it is more difficult for women to run in elections because women bear more burden of housework and childcare than men. In one study, researchers fielded an online survey to ask whether respondents would consider running for office, experimentally presenting scenarios where their partner helps or does not help them with housework (*3). It was found that female respondents were more likely to consider running in elections when they have support from their partner, but this was not the case for male respondents. The results suggest that the burden of housework may be one of the barriers to women’s political advancement.

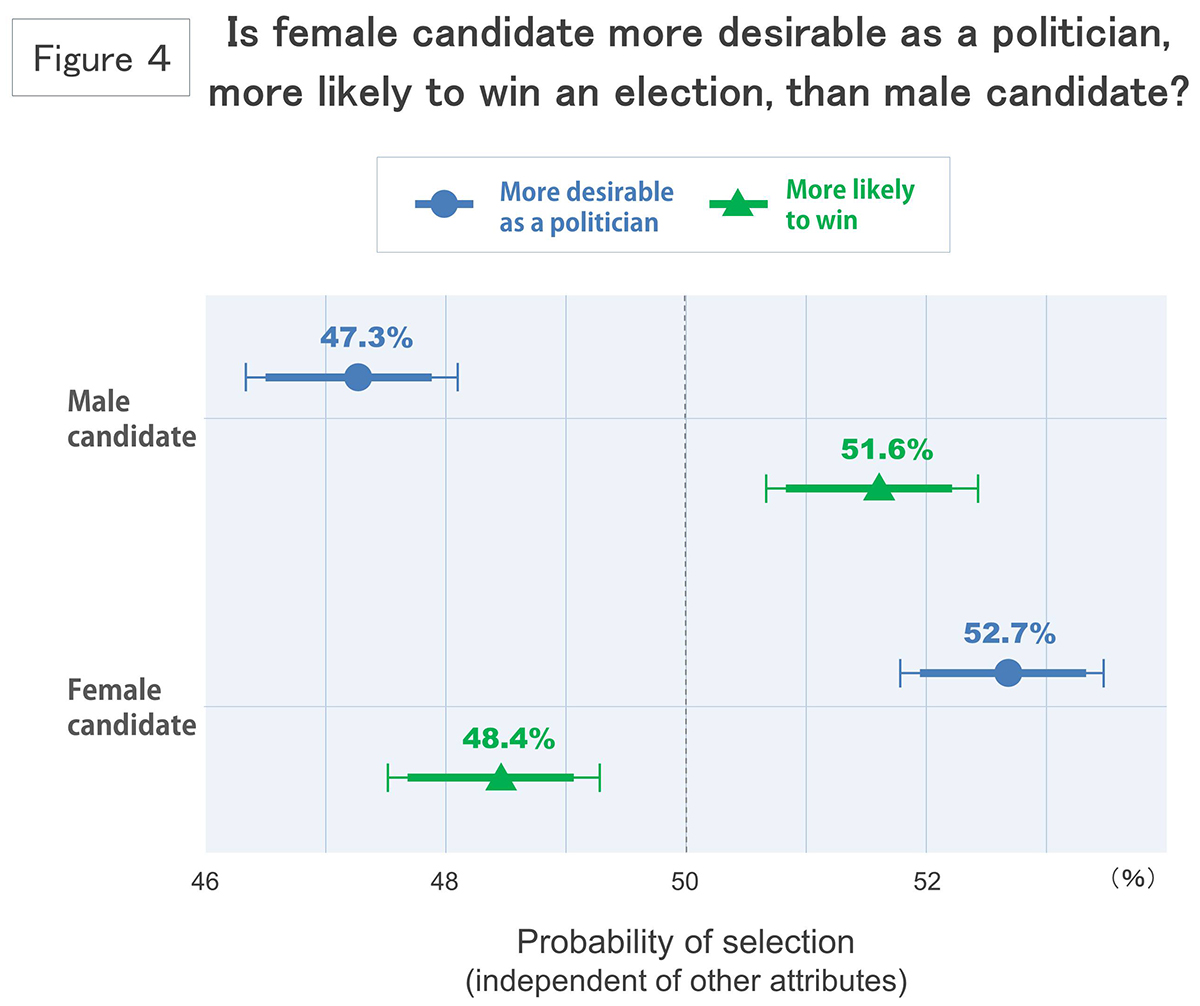

My research explores the alternative possibility that voters who prefer female candidates do not necessarily support female candidates in elections (*4). The focus is on the expectation that each individual has about the preferences of voters around them. I used a technique known as a conjoint experiment, which randomly presents hypothetical candidate profiles to respondents in an online survey and asks them about their preferences and perceptions of the candidates’ likelihood of winning elections. The experiment revealed that average respondents think female are desirable as politicians to male, but at the same time expect women to less likely to win elections than men (Figure 4). This result suggests that there is another hurdle to overcome for women to run and win in elections, as the degree to which female candidates are preferred tends to be underestimated.

When we are exposed to a variety of discourses, opinions, and news, we tend to accept them, assuming they are accurate information. Rather than being swayed by what is considered normal by society, question your own assumptions and reflect on them. You may see different answers, like we did in youth voter turnout or the percentage of women in parliament.

※2 Horiuchi, Yusaku, Daniel M. Smith, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2020. “Identifying Voter Preferences for Politicians’ Personal Attributes: A Conjoint Experiment in Japan.” Political Science Research and Methods 8(1): 75–91.

※3 Kage, Rieko, Frances M. Rosenbluth, and Seiki Tanaka. 2019. “What Explains Low Female Political Representation? Evidence from Survey Experiments in Japan.” Politics & Gender 15(2): 285–309.

※4 Kato, Gento, Fan Lu, and Masahisa Endo. In Press. “The Preference-expectation Gap in Support for Female Candidates: Evidence from Japan” Public Opinion Quarterly.

* The information contained herein is current as of April 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.