Are platforms not liable for scam-related damage!?

Losses from scams known as social media investment scams are continually reported. From January to August 2024, the police recorded 4,639 cases that caused losses totaling 64.1 billion yen. While most of the losses per victim were less than 5 million yen, some exceeded 100 million yen, creating a serious situation.

The government as a whole recognizes this as a major social problem, along with telephone fraud and romance scams, that requires urgent action, as outlined in the Comprehensive Measures to Protect People from Frauds adopted at the Ministerial Meeting concerning Measures against Crime on June 18, 2024.

The gateway to these scams is the impersonation of fake advertisements and posts on platform operators’ services, including social media. They use the names and photos of famous business people and economic analysts with endorsements in the ads and posts to attract people to fake investment-related services, such as investment courses.

From a legal perspective, the sender of fraudulent information is criminally liable for fraud (or as an accomplice) and subject to civil liability for damages to fraud victims. In addition, they are liable for damages to the impersonated celebrities for infringing on their portrait rights and rights of publicity.

What complicates this issue, however, is the fact that it is essential to consider the responsibility not only of the perpetrators of investment scams but also of the platforms that host fake ads and posts. Recently, it has been widely reported that celebrities whose likeness was used without permission have sued the platforms that hosted the ads, seeking damages and injunctions against the ads, while victims of fraud have also filed lawsuits against the platforms.

Even if a platform hosts information that lures its viewers into fraud and causes damage, the platform merely provides a space and no substantial causal connection to the damage can be established. Therefore, the platform is in principle not liable for damages, unless the platform, as an advertising medium, violates its duty of care to verify the authenticity of the information under special circumstances.

Information that conflicts with laws and information that violates the rights of others (rights violation information) is collectively referred to as illegal information. In fact, under the current legal system, there are few laws that impose a duty to remove illegal information that is not subject to civil liability on platforms providing a space for delivering it.

Nevertheless, the reality is that platforms allow fake ads and posts that serve as gateways to fraud and result in many victims. The public is unlikely to believe that there is no need for platforms to take any action.

Historically, an early legal framework to address illegal information on information networks was established around the time of the commercialization of the internet. In Japan, the Provider Liability Limitation Act (“PLLA”) enacted in 2002 and the related soft-law guidelines for businesses have addressed the issues.

The PLLA limits the liability of platforms for damages only to rights violation information among illegal information and operates a sender information disclosure system. The PLLA specifies, for example, cases in which the administrator of an anonymous bulletin board cannot leave rights violation information posted in a thread, can delete it, and can disclose the information on the poster, i.e., sender information. This deletion or disclosure may voluntarily be done without obtaining a court decision by referring to the soft-law guidelines.

However, nearly a quarter of a century after the first-generation legislation, the convenience of platforms such as social media has improved, while there are growing problems that cannot be addressed by the first-generation legal framework by simply limiting the civil and criminal liability of service providers and relying on their voluntary actions. Therefore, the EU and other countries around the world are now rapidly moving towards establishing legal responsibility to reduce the systemic risk of illegal and harmful information based on the scale of the platforms.

From the Provider Liability Limitation Act to the Information Distribution Platform Act

In Japan, the PLLA was revised in May 2024 and renamed Information Distribution Platform Act (“IDPA”), which will take effect within one year from the date of promulgation. The IDPA aims to address current pressing social issues by speeding up the response of platforms to rights violation, including online defamation and invasion of privacy, and by enhancing the transparency of the deletion practice of illegal and harmful information, including information that may not fall into the category of rights violation information.

The IDPA has established rules regarding responses to illegal or harmful information such as the deletion of posts (content moderation), which had been conducted at the discretion of businesses.

Specifically, platforms that meet certain size requirements (Large-scale Specified Telecommunications Service Providers (“LsSTSP”)) are now required to: (1) establish and publicize contact points and procedures for requesting removal of rights violation information; develop a system for responding to removal requests, including the appointment of persons with sufficient knowledge and experience; and provide decisions and notices regarding removal requests (expedited rules) and (2) establish and publicize removal standards that cover illegal and harmful information, including information other than rights violation information; disclose the status of content moderation practices; and notify posters when their posts are deleted (transparency rules). Penalties for violation of these obligations have also been added.

With regard to social media investment scams involving impersonating fake advertisements, first, if the platform itself is identified as the sender of the fraudulent information (or as an accomplice), it may be subject to criminal liability (fraud) and civil liability (for damages to fraud victims).

Second, even if the platform was not involved in the creation of the advertisement, if it is found to have violated the duty of care or the duty to delete as a publishing medium or an advertising agency, the platform will be held liable for damages to the fraud victims and for damages for the infringement of the portrait rights and the right of publicity of the impersonated celebrities.

In addition to these two points, which have remained unchanged in the existing legal system, the IDPA applies to the LsSTSP the expedited rules for dealing with the alleged rights violation information. Thus, for example, if a right holder requests that the relevant advertisement be suppressed owing to the infringement of portrait rights, the LsSTSP is obliged to make a prompt response and a decision.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications plans to issue guidelines for determining the applicability of illegal information, including advertisements. Impersonated celebrities whose portraits, names, and voices have been used in advertisements will request removal by referring to these guidelines.

The transparency rules under the IDPA include both illegal information regarding administrative regulations (e.g., illegal advertising on drag) which does not fall into the rights violation information and harmful information which does not fall into illegal information but is likely to incite crime (e.g., illegal Gun trafficking) or is false or fabricated (including false rumors) but with significant social impact. Harmful information, if not illegal, includes gray-area solicitations leading to so-called shady part-time jobs these days. Most fraudulent advertisements that do not involve impersonation also qualify as at least harmful information.

Under the transparency measures, if the platforms have established and published criteria for ads and posts in advance and have prohibited illegal and harmful information in addition to rights violation information, they will determine whether the criteria are met and be able to remove the ad or post.

These measures are primarily modeled on the EU’s Digital Services Act and are the result of an effort to minimally expand the current legal system. On the other hand, they represent a significant policy shift from a legal framework focused on rights violation information to one that legally addresses other illegal and harmful information as well.

Various issues concerning impersonating fake advertisements and platforms

So far, I have discussed platform regulation as a countermeasure against social media investment scams involving impersonating fake advertisements. When restricting advertising and posting, it is also necessary to consider the balance with constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression or the freedom of operators to conduct business.

Since the era of personal computer communications before the advent of the internet, the question of how far and under what circumstances, platform operators, who are not the direct senders, can and should intervene in various communications by users, has continually been discussed as an extremely difficult issue.

When a removal request is actually made concerning an expression on a platform, including web advertisements, a perception gap may arise between the user and the platform. For example, when a claim of defamation is made against an article or advertisement published by a commentator or politician, the platform may prefer to remove it to avoid litigation even if the user is determined not to withdraw it until a court decision is made.

There is also the perspective that platforms themselves have freedom of expression in addition to the freedom to conduct business. The Supreme Court once ruled that even if an individual with a prior arrest record requests an internet search engine to exclude the internet articles at the time of the arrest from search results, the legal interest in hiding them must clearly outweigh the value of providing such search results which “also constitute a form of expression.”

If content moderation by platforms is considered as a form of expression, no matter how much the government imagines an ideal form of content moderation by platforms, it is uncertain to what extent the government can impose it on them. This also raises the question of the extent to which the internet as important infrastructure should be considered a public sphere.

Against the backdrop of the recent proliferation of crimes such as fraud, rights violation information, including defamation becoming a social issue on social media, there is a strong argument for prohibiting anonymous information dissemination. However, aside from stricter identity verification for advertisers as business entities, I am personally opposed to a real-name policy for individuals. While it helps reduce harm to some extent, the downside is likely to be much greater given the chilling effect on important anonymous speech, such as courageous speech and whistleblowing.

As seen above, the issues of fake ads and investment scams on social media cannot be reduced to the simple conclusion that platforms should stop publishing them as soon as they are found, and this leads to related interesting discussions. In a way, this highlights the fascinating aspect of information law, where the Constitution, as well as criminal, civil, and administrative regulations, intersect.

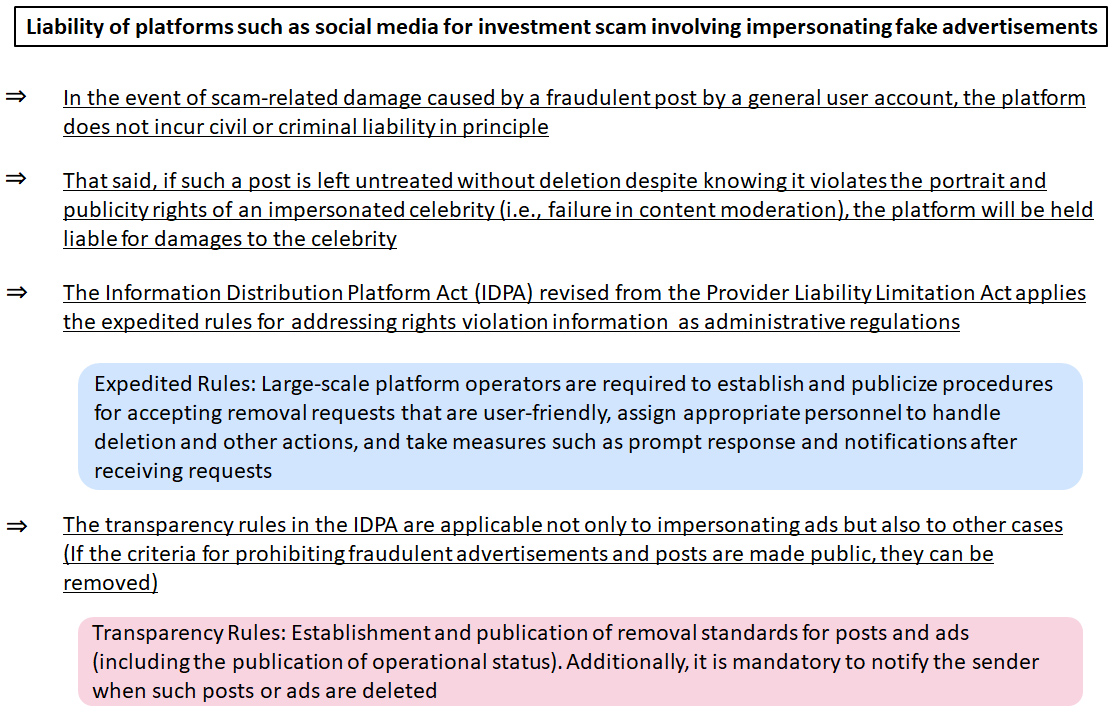

Liability of platforms such as social media for investment scam involving impersonating fake advertisements

In the event of scam-related damage caused by a fraudulent post by a general user account, the platform does not incur civil or criminal liability in principle

That said, if such a post is left untreated without deletion despite knowing it violates the portrait and publicity rights of an impersonated celebrity (i.e., failure in content moderation), the platform will be held liable for damages to the celebrity

The Information Distribution Platform Act (IDPA) revised from the Provider Liability Limitation Act applies the expedited rules for addressing rights violation information as administrative regulations

Expedited Rules: Large-scale platform operators are required to establish and publicize procedures for accepting removal requests that are user-friendly, assign appropriate personnel to handle deletion and other actions, and take measures such as prompt response and notifications after receiving requests

The transparency rules in the IDPA are applicable not only to impersonating ads but also to other cases (If the criteria for prohibiting fraudulent advertisements and posts are made public, they can be removed)

Transparency Rules: Establishment and publication of removal standards for posts and ads (including the publication of operational status). Additionally, it is mandatory to notify the sender when such posts or ads are deleted

* The information contained herein is current as of July 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.