Withdrawal from unprofitable products may cause the company to lose money as a whole

Variable costs are costs that increase or decrease in proportion to the level of production and sales, and fixed costs are costs incurred in a fixed amount regardless of the level of production.

For example, the direct material cost is a typical variable cost, and if you want to double the production volume, you need to double it. As the number of hours for direct working increases with the production volume, the wages of direct workers consumed also increase, so direct labor costs are also variable costs. The more you produce, the more it costs; the less you produce, the less it costs. That makes up the variable costs.

Fixed costs, on the other hand, are a set amount of costs incurred every month based on past decisions or contracts. Included in fixed costs are fire insurance premiums for factory buildings and equipment, depreciation of machinery, and so on. These do not go down just by reducing the production volume or stopping production. Also, the salary of the factory manager who is employed on a fixed salary is included in fixed costs.

If nothing is produced, variable costs will be zero, but fixed costs will result in a deficit. This is where we need to pay attention when we consider withdrawing from unprofitable products. Intuitively, it seems better to exit early and focus only on profitable products, but that is not always the case.

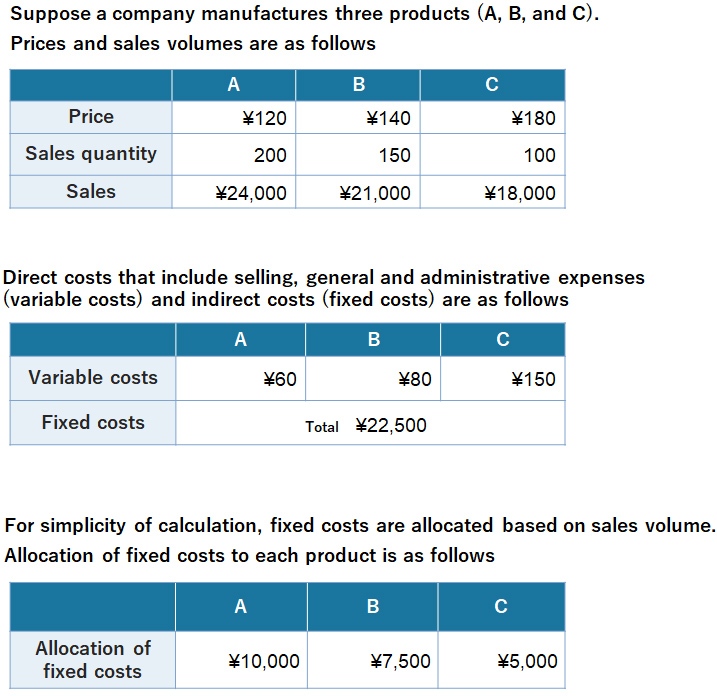

Let us take a very simple calculation example. Suppose a company manufactures three types of products: A, B, and C. The price and sales quantity are 120 yen for 200 units of A, 140 yen for 150 units of B, and 180 yen for 100 units of C. If we assume that all produced products are sold, the sales will be 24,000 yen for A, 21,000 yen for B, and 18,000 yen for C. In order to understand profit and loss, we have to think about how much it cost to get these sales.

The costs directly associated with producing a product are called direct costs, which are roughly equal to variable costs. Let us assume direct costs of 60 yen for A, 80 yen for B, and 150 yen for C. On the other hand, the costs not directly known to produce a product are called indirect costs, which are roughly equal to fixed costs. Fixed costs (assumed here to be the same as manufacturing indirect costs) are only known in total for the entire plant, so they must be allocated to A, B, and C on some basis. This is called allocation. For example, if the fixed cost is 22,500 yen and allocation is based on the production quantity (= sales quantity), 200 units of A would cost 10,000 yen, 150 units of B would cost 7,500 yen, and 100 units of C would cost 5,000 yen.

Based on this information, an income statement for each product is prepared. Contribution profit is calculated by subtracting variable costs from sales, and operating profit is calculated by subtracting fixed costs from contribution profit. In other words, while A has an operating profit of 2,000 yen and B has an operating profit of 1,500 yen, C has poor profitability with a loss of 2,000 yen despite its high unit price. As a result, an overall operating profit is 1,500 yen.

In this case, it is a big mistake simply to think that stopping the production of unprofitable C would reduce the deficit of 2,000 yen, and overall profitability would turn negative. This is because C makes a certain amount of sales and covers some of the fixed costs even though its profitability is in the red. In other words, if we withdraw from the product simply because it is a loss-making product, A and B will have to bear the remaining fixed costs, and there is a risk that the profitability of the company as a whole will decrease.

To do the fixed and variable cost breakdown, you need to follow the company’s data closely

Depreciation, which is classified as a fixed cost, cannot be easily reduced by withdrawing from a certain product. Without a clear understanding of the characteristics of variable and fixed costs, the overall performance could deteriorate further.

It is also important to see if there is demand. In the previous example, if resources from discontinued production of C are directed to produce A and B, it is meaningless if they are not sold and remain in stock. In the first place, it is not always possible to make 50 units each of A and B by the same resources to make 100 units of C. There might be a manufacturing machine that specialized in C, or there might be someone who worked for a long time to make C. Even if those people are directed to the production of A and B, we do not know if they can produce the same quantity with the same labor.

Unlike variable costs, it is hard to reduce fixed costs once they have increased. Among fixed costs, those that are easy to manage even in a relatively short period of time, such as expenses for advertising and research and development, are called managed capacity costs. Those that cannot be changed for a long period of time, such as personnel expenses for regular employees and depreciation expenses for purchased factories and industrial machinery, are called committed capacity costs. Of these, the latter is especially important. Reducing the number of employees hired as regular employees and cashing in on the machinery and factories that have been installed involve hardship and difficulties.

In recent years, it has become a topic of conversation, but Hitachi has withdrawn from home air conditioners, which are being developed by various manufacturers and are already facing excessive competition. But it was not just stopping the factory line. Instead, Hitachi sold the business itself. In other words, the entire fixed costs were transferred to an external company. Because cost structures vary widely from company to company, decisions and methods for withdrawing from unprofitable products will vary from company to company.

If the fixed cost ratio is large and the variable cost ratio is small, profit may increase even with a large discount

The concept of the fixed and variable cost breakdown is also important when considering sales strategies. For example, if you break it down into fixed costs and variable costs, you can better understand the meaning of so-called economies of scale. As the production volume increases, the fixed cost per product decreases, so mass production is basically easier to sell at lower prices. The variable cost per product is not affected by the scale, but the fixed cost varies depending on the scale.

The fixed and variable cost breakdown also plays a role in whether or not you accept special orders. What if we receive a request to buy in bulk at a much lower price than the regular price we usually charge other companies? If you have already calculated the profit and loss including the fixed cost for selling to other companies, the only cost incurred by additional orders is the variable cost, so you can make a profit if the price is higher than the variable cost.

Speaking of familiar examples, it may be easy to understand if you imagine kaedama (refill) for ramen. If the selling price of kaedama for ramen is 100 yen, the additional cost to serve is about the cost of ingredients for noodles. We pay the same salary to the staff regardless of whether there is an order for kaedama or not, and the pot for boiling noodles is kept boiling during business hours. The additional cost is only the variable cost of noodles, so you can make a profit from the difference.

In the service industry, too, if the ratio of fixed costs is relatively large and the ratio of variable costs is relatively small, it is important to reduce vacancies.

In a hotel, variable costs account for a small percentage of the total cost, so it is important not to create vacancies. Also at golf courses, the price difference between weekdays and weekends is almost double. The fixed costs do not change, so it is important to fill the vacant slots. Weekday discounts at movie theaters can be said to be a discount service based on this idea. The screening cost is fixed, so it is better to get people to enter even if you give them a discount.

The fixed and variable cost breakdown is something that anyone who is educated in the School of Commerce or the School of Business Administration knows as a matter of course, but when it comes to specific decisions, product withdrawal, and profitability management, we need to understand it even better. If you do not know how this works, you will not be able to see how much you can discount in your business or how you can withdraw from it, so why not delve further into it if you need to?

* The information contained herein is current as of August 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.