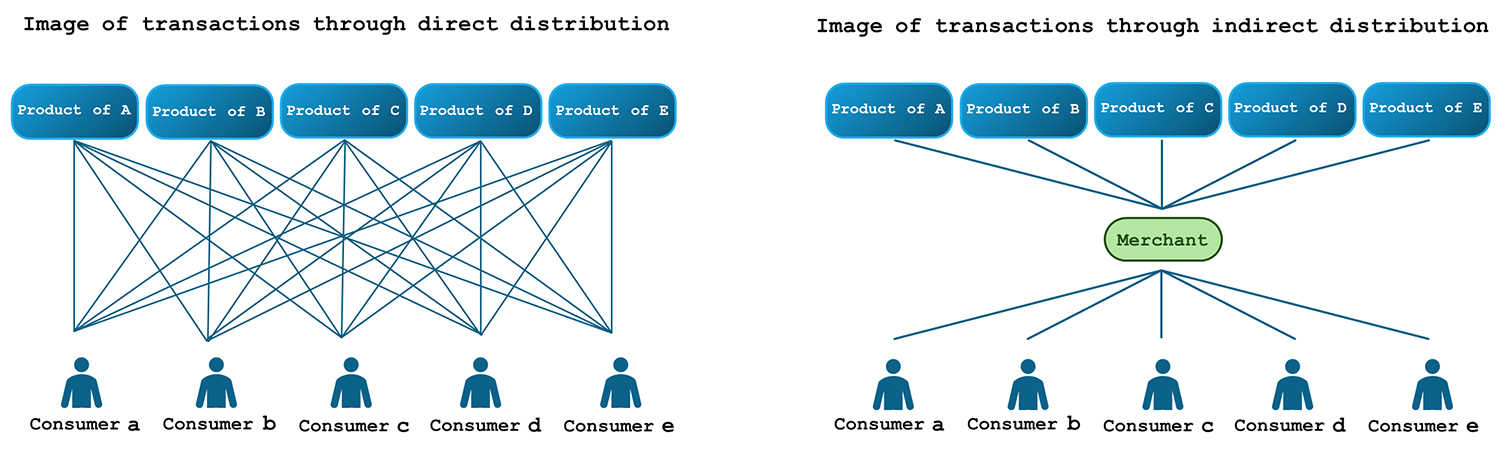

Indirect distribution system to bridge the gap between production and consumption and to reduce the number of transactions

In modern society, indirect distribution is predominant, whereby merchants distribute products. We use over 1,000 items within an hour at most between waking up and going to work. It would be virtually impossible to obtain all of this through direct distribution. An indirect distribution system, in which a variety of items produced or harvested in various locations are collected in one location and then distributed to consumers, reduces the number of transactions and improves economic rationality, so the world has now adopted this system.

For example, if 5 consumers each receive products from 5 places and there are no merchants involved, then each consumer will have to trade with each of the 5 places, resulting in a total of 25 transactions. On the other hand, if a merchant is involved, each consumer can visit there and buy products from all places, and the total number of transactions is only 10. Indirect distribution can bridge the gap between production and consumption, reduce the number of transactions in society, and improve efficiency. This led to the establishment of the method of concentrating agricultural, livestock and fishery products from various places in major cities, from which they are distributed to surrounding regional spots.

So when, by whom, and how was the product distribution system established in Japan? Postwar Japan, regarded as a developing country, focused investment on specific industries, such as steel and coal, and moved toward industrialization to revive its economy. At that time, small and micro retailers were dominant, and the distribution was inefficient, requiring shops such as fishmongers, greengrocers, and geta-ya (clog shops) to distribute each product. In fact, it was unknown entrepreneurs who reformed the product distribution system, which had been neglected as a government policy.

Around 1960, ambitious young entrepreneurs, aiming to modernize product distribution, started introducing a modern distribution system of large-scale concentration, a mechanism to widely distribute products throughout Japan, using the methods of the chain-store theory brought over from the U.S. For example, Daiei Pharmaceutical Industry, which was founded in 1957 and later became Daiei, opened its first store in Sannomiya, in Kobe City, the following year in 1958. As they promoted chain stores and devised sales ideas, they grew quickly. The construction of expressways throughout Japan into the 1990s also helped to build a highly efficient distribution system in Japan.

Their philosophy was to create a large-scale, efficient product distribution system that links mass production to mass consumption. It is based on the belief that selling good products in large volume will make us happy. Mass production and consumption was the symbol of affluence.

Japan’s advanced product distribution system that allows fresh, perishable foods to be purchased anywhere

The distribution of industrial products dominated by global companies is now well organized in many countries. The supply of products such as those from the fast fashion giants is overwhelming and equally available everywhere in the world.

On the other hand, Japan’s advanced distribution system covers groceries (perishable foods). Its greatness is obvious when you look at the selection of vegetables at your local grocery store. Although meat and fish can be distributed frozen, there is no other product distribution system in the world that can supply such a wide variety of fresh, raw vegetables every day. I think this has something to do with the fact that many Japanese prefer perishable food, where freshness is important, and are sensitive to freshness. Inbound travelers usually do not cook in Japan during their stay, so it is not often discussed, but it is something about which Japan can boast to the rest of the world.

These days, it is well known that foreign travelers to Japan are fascinated by Japanese convenience stores and drugstores. There is also no system in the world that can open so many small stores and efficiently supply such a wide range of products. This is only possible because we have the technology that allows us to control large-scale systems down to the finest detail.

The ideal product distribution system is closely related to the culture and perception of happiness in each country

Regularly taking advantage of Japan’s sophisticated distribution system, I sometimes think that foreign distribution systems could be improved. However, each country has its own circumstances, so it is futile to demand other countries to think the way we do.

When I started living in Poland in 2015, I pointed out to my friends that the sandwiches sold at convenience stores would run out by the afternoon: “Wouldn’t it be better to make the product distribution system more efficient? You must have experienced being able to buy products 24 hours a day at convenience stores in Japan.” “We don’t eat sandwiches at 16:00,” they responded. Their routine is to go home at 16:00 to pick up their children and have dinner at home, so that is sufficient for them.

An Austrian friend wondered, “Why does Japan transport local produce to other places?” Local product is (should be) consumed locally. Seasonal foods are consumed only in their seasons. This is the choice of many people abroad. In Poland, cabbage is eaten only in spring, and in the Netherlands, white asparagus is available only in spring. They are fine with that.

The point is that they are not seeking the same product assortments as Japanese supermarkets. Even though inbound travelers rave about Japan’s product distribution system, they do not adopt it at home. This result may be partly because many foreigners do not eat as much perishable food as the Japanese do, but is probably because they consider their current system to be sufficient.

The excellence of Japan’s product distribution system does not mean it will prevail all over the world. They do say it is inconvenient, but they live by adjusting to their current system. When they come to Japan, they are happy to be able to eat and drink everything 24 hours a day, but they are negative about bringing it to their country to make them happy. Because the product distribution system is directly connected to the consumer, each is adaptive and special. So it is not effective to take the Japanese system overseas.

Moreover, it is meaningful as a tourism strategy to consume local food locally. This is also true in Japan. Large shopping malls with luxury brands wherever you go are convenient and efficient, but local shopping streets with unique local products have their own appeal.

Furthermore, Japan’s distribution system relies partly on large-scale supermarkets, which require large amounts of sales to maintain. This was not a problem when the population was increasing, but now the situation is changing. The population is decreasing at an accelerating rate, and high-volume selling is no longer working. With large supermarkets closing one after another, it may be time to review the distribution system itself.

The idea of becoming happy through consumption has shaped Japan’s prosperity. Today, however, more and more people value experience over consumption, and some even view consumption as a source of happiness as a poor concept. The ideal product distribution system would depend not only on convenience, but also on cultural background and what is perceived as happiness.

* The information contained herein is current as of February 2025.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.