Serious air pollution in Britain during the Industrial Revolution

Environmental problems, including global warming, are international and global challenges that can no longer be resolved by one country alone. The Paris Agreement, which took effect in 2016, calls for keeping the global average temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C.

However, the Trump administration withdrew the United States from this international framework. The reason, the president claims, is that emerging and developing countries are not meeting their greenhouse gas reduction obligations well, leaving the United States with an unfair burden. He also criticized the Green Climate Fund for supporting developing countries as a rip-off and announced the suspension of funding.

In this way, when environmental problems become an international challenge, differences in interests between developed and developing countries are inevitably highlighted. The disparity in the approach to the environment between the two groups, which have different technological and financial capabilities, may be unavoidable.

This situation is actually quite similar to that of 19th-century Britain. I am studying the economic history of Britain during the Industrial Revolution, particularly urban environmental problems. At that time, the heavy use of coal in Britain caused serious air pollution.

Britain was the first country in the world to experience the Industrial Revolution, a major technological breakthrough. The introduction of steam engines advanced mechanization and factories began to grow in urban areas.

The Industrial Revolution not only established capitalism but also determined the significance of the use of fossil fuels as an energy source in industry. This led to a sharp increase in coal consumption, and smoke began to fill the cities.

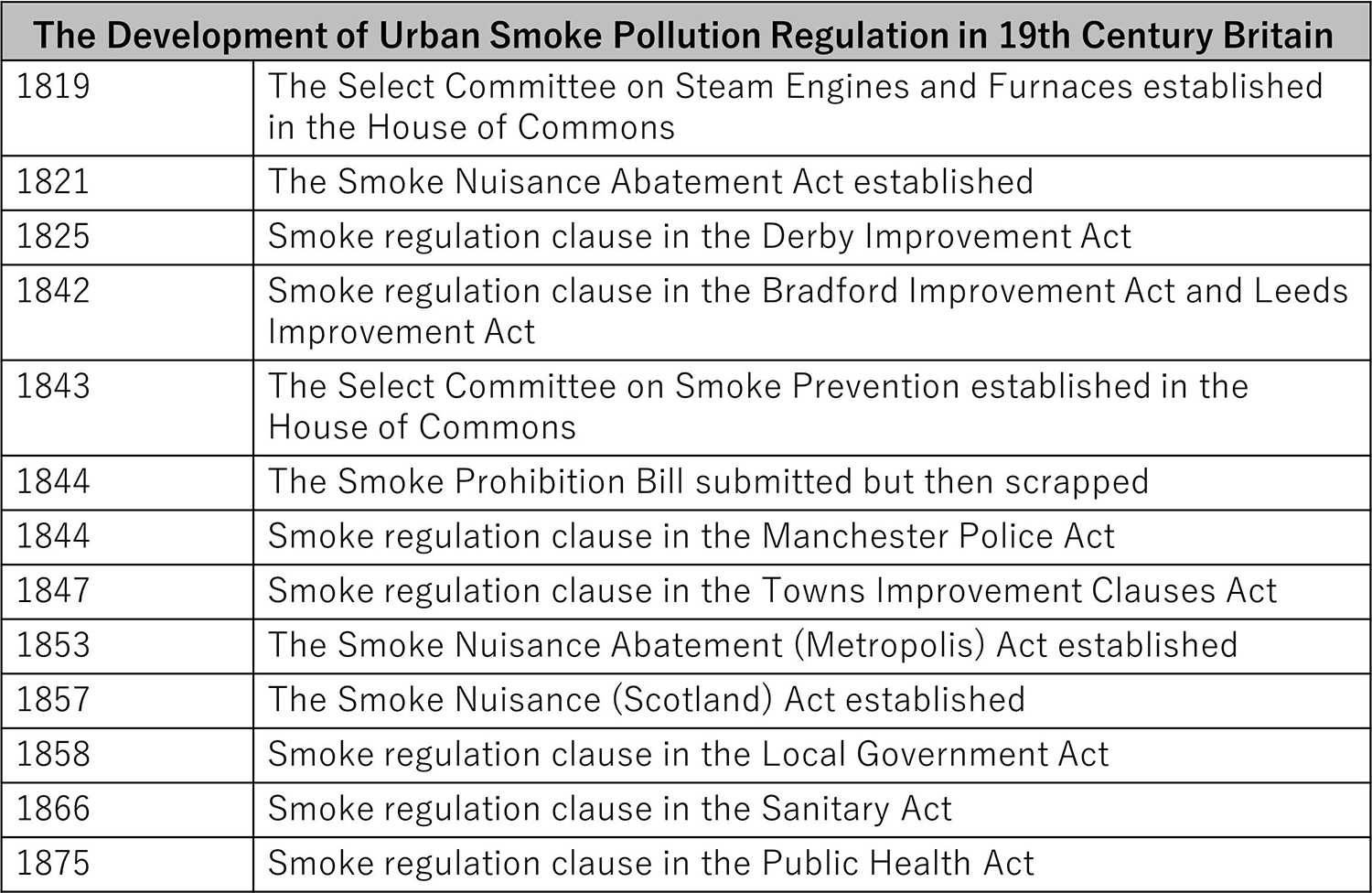

The air pollution at that time was called “smoke nuisance” and had a serious impact on the living environment and property. In response to the nationwide problem of smoke nuisance, local governments throughout Britain and the national parliament promoted legislation to suppress smoke nuisance throughout the 19th century.

It required smoke-emitting manufacturers to use some kind of smoke prevention technology and fined those who violated the legislation.

As a matter of fact, many previous studies on air pollution in Britain have shown that such legislation largely failed owing to the resistance of industrial capitalists and the absence of anti-smoke campaigns by urban residents.

However, my review of the historical records has revealed that some of the factory owners and entrepreneurs who generated smoke were, in fact, actively in favor of laws and regulations concerning smoke nuisance, and their influence enabled the introduction of regulations.

Why capitalists and factory owners supported the regulation of smoke

The main reasons why some factory owners and entrepreneurs were proactive in smoke regulations are (1) they themselves suffered damage from smoke; (2) the introduction of smoke prevention technology led to fuel savings; and (3) they were interested in preserving coal, a limited resource.

In the first place, smoke causes damage by staining the exterior walls of buildings and plants in gardens black and significantly reducing the asset value of real estate. At that time, health damage was not scientifically clear, and many of those who complained about smoke damage were wealthy people who owned land and property.

Furthermore, industrial capitalists and factory owners were also victims of smoke in a sense. In particular, the textile industry, such as cotton and woolen fabrics, used to have a process to dry products outdoors, so the soot in the smoke stained the products and led to losses.

Under these circumstances, starting with the establishment of the Smoke Nuisance Abatement Act in 1821, various regulations were enacted in Britain by the national and local governments to suppress smoke nuisance.

The introduction of smoke prevention technology that mandated these regulations primarily assumed the use of new furnaces equipped with smoke prevention devices such as air admittance valves and automatic coal feeders. (By the way, James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine, played a part in developing this technology.) The scope of the regulation was initially heating furnaces for steam engine boilers, and later expanded to include general industrial furnaces (excluding blast furnaces) and steamships.

Since smoke, in the first place, is generated by incomplete combustion of coal, approaching complete combustion will prevent smoke nuisance and reduce fuel costs at the same time. Therefore, many industrial entrepreneurs felt confident about the new furnaces introduced as anti-smoke technology.

In fact, a London brewer reportedly saved around 5,000 pounds in fuel costs over five years by installing the new furnace.

Furthermore, the fuel saving effect of the new furnace came to be recognized not only as a matter of profit for individual companies, but also as a significant effect for the overall industry and the overall national economy in the form of conservation of limited national resources.

During this period, coal was an extremely important energy source for Britain. Black smoke spewing from a factory meant that the coal was not burning efficiently and that the precious resource was being wasted.

Therefore, the introduction of the smoke prevention technology that improved combustion efficiency, namely the new furnaces, was an important national initiative.

So, as previous studies often point out, why did the smoke regulations that should have been implemented with industry consent fail?

Closing the disparity in environmental efforts

A possible background is the conflicting interests between different industries and companies of different sizes. For example, we know that most industrial entrepreneurs who took a positive stance on regulations ran large businesses in the textile industry.

In contrast, industries other than the textile industry were often reluctant to take measures against smoke nuisance. The coal mining and steel manufacturing industries, which used extremely inexpensive coal, used unmarketable and inferior coal to fuel steam engines, so the benefits of fuel conservation through the introduction of new furnaces were probably limited.

In other words, the high cost of introducing the smoke prevention technology, which did not benefit them, was perceived as a heavy burden for business owners.

In addition, small and very small enterprises did not have the financial resources to finance the initial investment, even if they expected future benefits from fuel savings.

After the Industrial Revolution in Britain, the specialization of industries by region progressed. For example, in Birmingham, where metalworking was flourishing, it is known that the large number of such small-scale enterprises delayed the implementation of measures against smoke nuisance.

In short, in 19th-century Britain, despite the establishment of various regulatory laws, there were differences in the implementation of measures depending on the region and industry. As a result, it was not until after World War II in the 20th century that thorough nationwide measures against smoke nuisance were implemented.

The Great Smog of London in 1952, known as the worst air pollution in history, killed a huge number of people owing to health issues caused by air pollutants in the smoke. This gave momentum to the anti-smoke campaigns among citizens, and the Clean Air Act enacted in 1956 established a system under which the national and local governments subsidized anti-smoke measures.

The history of anti-smoke measures in Britain teaches us that disparity in technology and financial resources are obstacles to taking measures against environmental problems in the real world.

In particular, it can be concluded that support by the national and local governments, such as subsidies and grants, is crucial to small businesses that lack their own funds and industries that have little economic benefit from the measures.

The same would apply to the current global warming problem. There is a clear economic disparity between the less developed countries, which use inexpensive but environmentally damaging energy sources using old technologies, and the developed countries, which use high cost but environmentally friendly energy using new technologies.

In this situation, it is realistically difficult for the underdeveloped countries to respond without the support of the developed countries. As long as there are disparities in technology and finance, I think it is necessary for developed countries to lead environmental efforts.

What I am studying is just a single-country case of 19th-century Britain, but even within Britain, there were disparities between regions and industries, and some regions had advanced measures while others did not. I think this situation can be applied to discussions on expanding environmental subsidies and grants for small and medium-sized enterprises and households in contemporary Japan.

Learning from past mistakes and applying lessons to contemporary policies. I think that is one of the important roles of economic history research.

* The information contained herein is current as of February 2025.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.