More people believe that luck is the key to success

There is an international research report called the World Values Survey. Beginning in 1981, it now reveals the subjective perceptions of people in approximately 120 countries and regions. One of its questions is whether hard work brings success or it is more a matter of luck and connections. In other words, the question asks whether the society to which one belongs is perceived as hard work oriented or luck oriented.

The answers tend to be hard work oriented in developed countries, such as those in North America and Europe, and luck oriented in developing countries, such as those in South America and Africa. In the latter countries in particular, the lives of children are often influenced by factors such as their parents’ financial power, and corrupt politics tend to lead to nepotism unrelated to merit, so I think this result is understandable.

In a society where hard work is generally considered to be rewarded, there are plenty of opportunities to become wealthy if you have the skills, or many people believe there are. So governments, like that of the U.S., tend to set lower tax rates to incentivize people to work. On the other hand, in a society where hard work is considered unrewarding, the government policy that collects more taxes from the wealthy and redistributes them to the whole is more likely to be justified to some extent.

So, what is the mindset of the Japanese people? In Japan, as in other developed countries, the hard-work-oriented opinion predominates, but in fact, compared to the 1990s, the number of people who think that “in the long run, hard work usually brings a better life and success” is on the decline.

In particular, in the most recent survey in 2024, its ratio was 52.5%, down 9 percentage points from the previous survey in 2019. In contrast, the percentage of respondents who answered that “hard work does not generally bring success – it is more a matter of luck and connections” had increased to 44.9% (“World Values Survey 1990–2024 Japan Time Series Analysis Report,” DENTSU SOKEN and Doshisha University).

As the recent buzzword oyagacha (parent lottery) suggests, the view of society that one’s parents’ financial power and environment greatly affect one’s life may be prevalent in contemporary Japan. There are also arguments that point to the progress of the so-called unequal society as its background.

However, when it comes to the question of whether the inequality is actually widening, the answer is not a straightforward yes. Prior studies have not yet found evidence that inequality has widened sharply over the last 20 years or so. On the other hand, I do not think you feel that inequality is narrowing either. What does this mean?

The widening inequality theory has many reasons

For many years, I have been studying economic inequality in society from a macroeconomic perspective. When we hear about economic inequality, we tend to think of differences in salaries and incomes, but from the perspective of economics, these are not sufficient. To measure true inequality, we must cover comprehensive future prospects in income, assets, savings, and spending, rather than focusing on earnings at a single point in time.

In addition to income, we base our lives on the assets we inherit from our parents, educational opportunities, health, and other factors that affect our life plans. Therefore, when we think about inequality, we need to look at the data from a long-term perspective.

In Japan, after the collapse of the bubble economy, the era of the “100 million middle class people” came to an end, and the issue of economic inequality began to attract attention. I graduated from college in March 2000, and the generation around me is known as the Lost Generation.

Many of the generation that job-hunted around this time were unable to find good jobs and were forced to become non-regular employees or part-time workers. Since then, the Lost Decade has been extended to the Lost 20 Years and the Lost 30 Years, leading to the present situation. My once-young peers are now middle-aged, and their economic woes are also affecting the current low birth rate.

An analysis of economic inequality during this period based on various data shows that the inequality has actually been widening since the 1980s, when the economy was in the midst of the bubble economy. However, the situation at the time was such that the wealthy became even wealthier, and the properties were different from those of the economic inequality that followed.

From the 1990s to the 2000s, there was a growing trend of slower growth of the top segment, while the bottom segment became more impoverished. Naturally, social anxiety becomes more significant in this situation.

And from the late 2000s to the 2010s, at least in terms of the data, the widening of economic inequality appears to have settled down temporarily. However, of course, this does not mean that inequality has been corrected, and the trend of the poor becoming poorer is continuing.

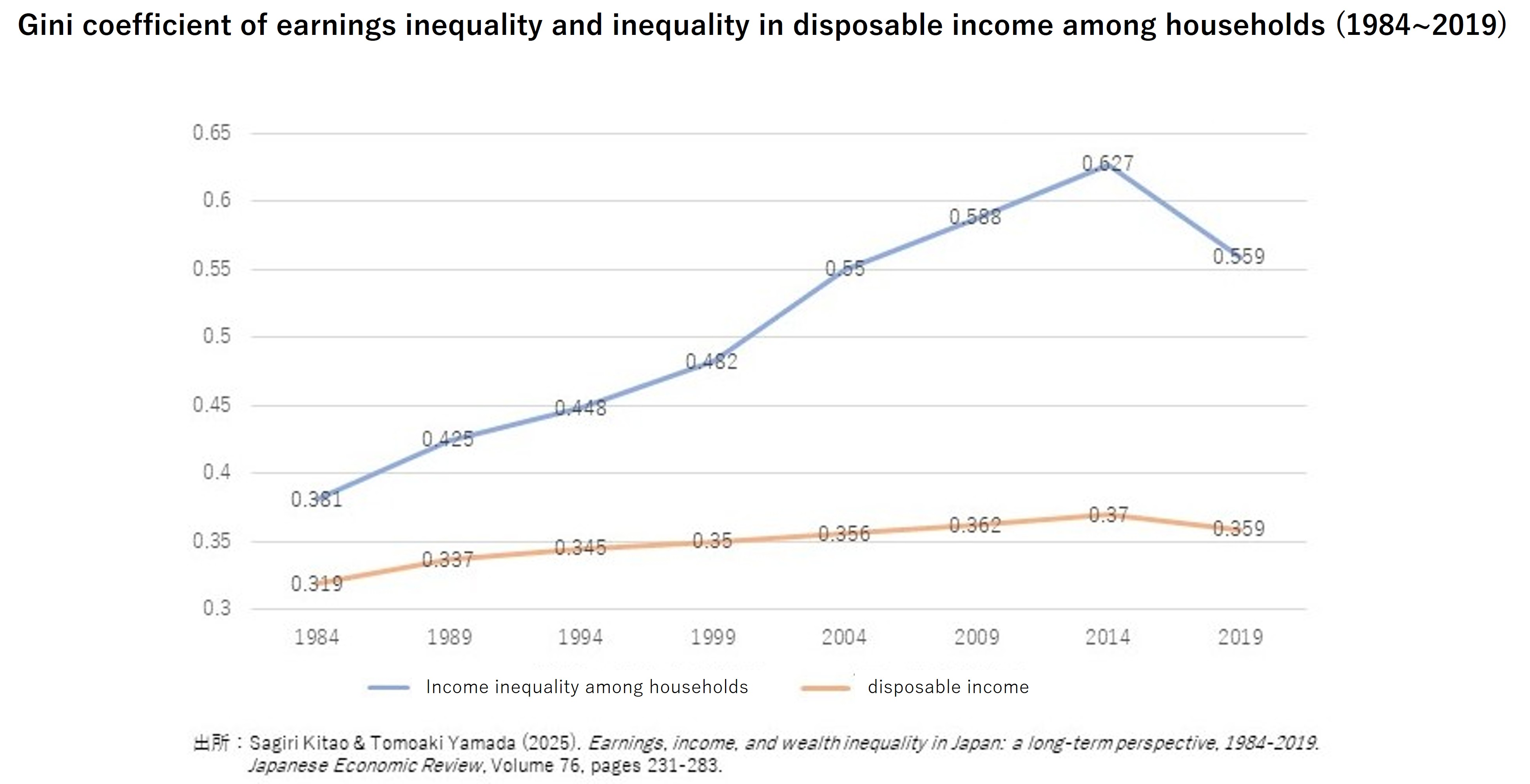

Let us examine the actual data. My co-researcher and I have conducted an analysis using the National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure (NSFIE) and National Survey of Family Income, Consumption and Wealth. The results show that the Gini coefficient indicating the earnings inequality among households rose from 0.38 in 1984 to 0.56 in 2019, and the inequality in disposable income, or the amount of take-home earnings that can be used freely, also widened from 0.32 to 0.36.

Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, such economic inequality did not widen monotonically. In particular, the widening inequality in the 2000s was caused by a decline in the income of households in the middle or lower segments, and a further worsening economic situation for people who are already struggling to make ends meet is unacceptable.

The prescription for inequality is Japan’s economic growth

Many would agree that economic inequality is a social problem. However, when it comes to how to fix it, opinions are divided. Simply collecting taxes from the wealthy and distributing them to the poor is not a fundamental solution to the problem. We need to understand exactly what the background to this inequality is.

In addition, to understand the reality of inequality correctly, it is insufficient to look only at the difference in current income. For example, a significant disparity appears in income among middle-aged and older people, but this is due to differences in past work history and experience, and not necessarily unfair. Analysis from a long-term perspective is necessary, considering not only income but also assets and even future income prospects.

I have conducted research using individual data from the Family Income and Expenditure Survey and NSFIE conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. By using sophisticated data called microdata, we can more accurately understand the economic situation at the individual and household levels and identify the factors that are widening inequality.

In recent years, the analysis of inequality using tax and administrative data is also advancing globally. In the U.S., everyone files their tax returns, so the government possesses a huge amount of income data, which it uses to analyze long-term income trends and changes in inequality.

So how should we confront the entrenched economic inequality in Japan? In my view, what is more important than individual measures to address inequality is to achieve overall economic growth.

In a society with a growing economy, your earnings will gradually increase, even if your income is relatively low, giving you hope for the future. Actual surveys have also shown that many people prefer a situation in which their living standards steadily improve year after year to one with significant fluctuations in annual earnings.

In Japan, however, the average household earnings peaked in 1994 and have been stagnant ever since. In many countries, the more recent the data, the higher the average income, but in Japan, prices and wages have barely risen for many years, and economic growth has stagnated.

Although somewhat paradoxical, in order to break down the entrenched economic inequality, we should aim for economic growth that enables all segments of the population to increase their income, even if only gradually. Rising prices are currently being highlighted as a social issue, but inflation itself is a result of sound economic activity. What is important is that wages rise along with prices to maintain real purchasing power.

And the keys to economic growth are education and innovation. In Japan, where infrastructure is already established, we should focus on developing human resources and creating new industries rather than on public works. Excellent education fosters creative human resources who develop innovative technologies and businesses.

The U.S. has achieved growth in the ICT sector by gathering talented people from around the world in Silicon Valley and creating an environment where new ideas emerge one after another. I believe that Japan, too, needs to invest in young people who will lead the future and develop mechanisms to support creative challenges in order to achieve sustainable growth beyond economic inequality.

* The information contained herein is current as of May 2025.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.