A look at the declining birth rate from the perspective of demography

My area of expertise is demography. Demography has two areas of focus: one focuses on the actual changes in the population and the other examines the relationship between population change and social, economic, political as well as biological, genetic, and geographic factors. In order to explore such themes, credible statistics are essential. Demography, which involves examining such statistics, is an extremely data-oriented discipline. It goes without saying that Japan’s declining birth rate is in a critical state from the perspective of demography as well. For instance, the total fertility rate required to sustain Japan’s population (replacement level) is said to be 2.07. The 2005 total fertility rate, which was an all-time low at 1.26, was roughly 60% of the replacement level. Based on this total, it can be estimated (through simple arithmetic) that the population of children of that generation will amount to 60% of their parents’ generation. If this trend continues for two generations, the population of the grandchildren’s generation will drop to 36% of the parents’ generation. Will Japan be able to sustain itself under such circumstances? The Japanese government, of course, did not just sit there, and has implemented a variety of measures. As a result, the fertility rate rose back to 1.46 in 2015. But fertility rate refers to the number of children that were born that year compared with the population of women (to put it simply, number of births ÷ population of women between ages 15 and 49). The population of women (the denominator in the above calculation) has declined each year since the second baby boomer generation. Therefore, it will appear (mathematically) that the fertility rate has grown slightly. This does not mean, however, that the decline in the fertility rate has slowed down significantly. In actuality, the number of births, which was at 1.063 million in 2005, was 1.005 million in 2015. If this trend continues, the number of births is expected to drop below the 1 million mark this year (2016). Why then has birth rate declined this much? Let’s explore the causes as well potential measures from the perspective of demography.

Fertility rate trends and the causes

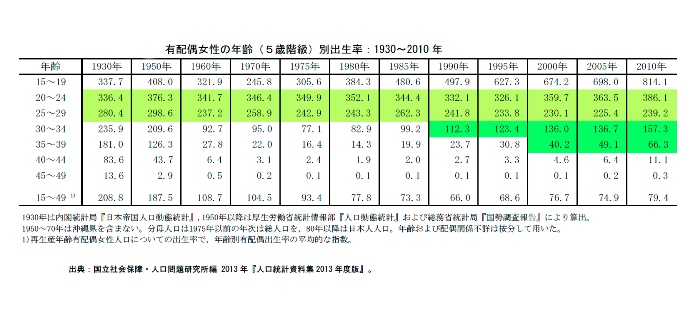

Table 1 Fertility rate according to age group (split up into every five years) of women with spouses: 1930 to 2010

Table 1 Fertility rate according to age group (split up into every five years) of women with spouses: 1930 to 2010

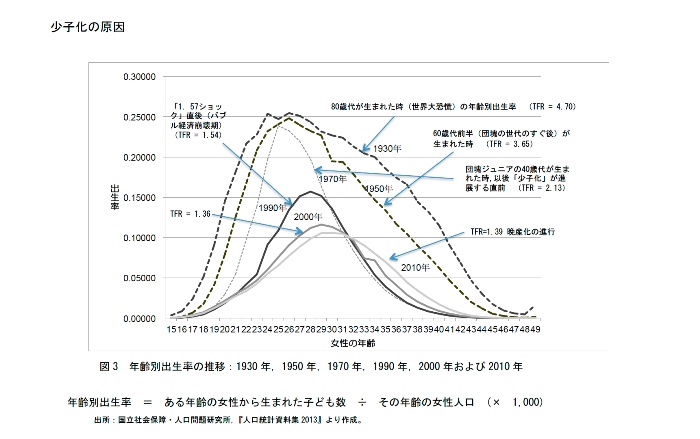

Graph 2 Causes of the declining birth rate

Graph 2 Causes of the declining birth rate

Do Japanese women no longer want children? I don’t believe that’s the case. Table 1 shows the fertility rate according to the age of women with spouses. In looking at the data, the 2010 fertility rate for women in their 20s is not significantly different from the figures from before 1970, when the fertility rate exceeded the replacement level. The fertility rate for women in their 30s reached its peak beginning in 1960. In other words, married women were having children. Similarly, in a 2010 survey targeting married couples on their plans for having children (Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research), the average number of children the survey participants wanted was 2.07. The average for a similar survey conducted in 1977 was 2.17, which means that the number of children that Japanese married couples want to have has not changed significantly. Why then has the birth rate declined?

Graph 2 shows fertility rate trends according to year and age. The fertility rate in 1930, when the peak of the curve is at its highest, was 4.7. This means that Japanese women during this time had about five children over their lifespan. In looking at age, the peak age for childbirth was between 24 to 26, and women continued to have children until just before the age of 50, which is close to the age of menopause. In the 1950s, while the peak age for childbirth (about 26) remained about the same as the 1930s, the number of births given by older women decreased. The main reason for this was the emergence of the concept of birth control. The idea was to have fewer children and raise them with care. The two-child model (based on the belief that the ideal number of children to have is two) became widespread, and it became common for people to have abortions if they conceived a third child. By the 1970s, while the peak age for childbirth remained the same, the number of children women had after the age of 30 saw a sharp decline. This resulted because the use of contraceptives such as condoms became widespread, and married couples aimed to control the number of children they conceived through careful planning. The fertility rate during this time was 2.13, which was at the replacement level.

Then in the 1990s, the graph curve took a sharp turn. The peak age for childbirth rose to about 28, and the size of the curve as a whole became much smaller. It was during this time that society underwent major changes. The 1973 oil crisis brought about a shift in the industrial structure, and heavy industries were replaced with high-tech industries (which provided small and light products) as well as service industries. This created more employment opportunities for women. The Equal Employment Act was enforced in 1986, and women advanced into society. It was also during this time that there was a sharp increase in the number of women who received higher education (such as a college education). The latter half of the 1980s saw the emergence of the bubble economy, and major corporations began hiring large numbers of recent graduates. Salaries also skyrocketed. Under such societal circumstances, the number of unmarried women, women who married late, and women who chose not to marry grew significantly.

In the 2000s, the number of women who gave birth in their 20s continued to drop, and the

gradually declining curve showing the number of women who gave birth in their 30s was nowhere to be found. By 2010, the peak age for childbirth rose to about 30, and the shift towards marrying late became noticeable.

In looking at these results, we can see that as the trend for women to receive higher education and advance into society continued, women began to marry later or remain unmarried, and therefore have children later. Furthermore, the earning capacity of men compared with women has declined, and because of this, men as well as women are marring late. As a result, the average age for women to have their first child, which was at 25.7 in 1975, has risen each year, reaching 30.1 by 2011. This total continued to rise and reached 30.6 in 2014 (“Summary of Annual Totals (approximate figures) from Monthly Reports for 2014 Vital Statistics” compiled in 2015 by Demographics and Health and Social Statistics Division, Statistics and Information Department, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). Generally, women gradually lose the ability to conceive naturally around the age of 37. If a woman has her first child at age 31, having a second or third child becomes extremely difficult. This is the main difference between now and 1970, when the fertility rate was 2.13.

Declining birth rate caused by late marriage and childbirth

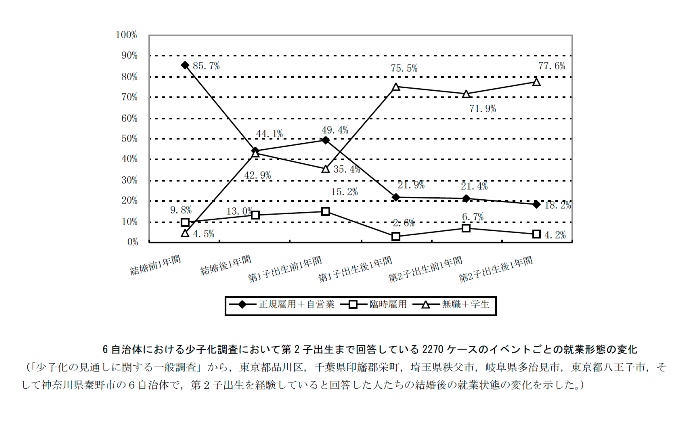

Graph 3 Changes in employment status of 2,270 people who answered a survey on the declining birth rate in municipalities (up until their second child) according to event.

Graph 3 Changes in employment status of 2,270 people who answered a survey on the declining birth rate in municipalities (up until their second child) according to event.

In a survey on what people considered or valued as criteria for choosing a spouse (“Summary of Results of National Survey Targeting Singles on Marriage and Childbirth: the 14th Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends” compiled in 2012 by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research), a high percentage answered “personality,” “ability to do household chores,” and “understanding of the line of work they’re in”. This was the case for men as well as women. In other words, women look for the same criteria in men that men look for in women. This is because while women will consider and value the earning capacity of men, they do not plan to depend on them entirely as women did in the past. The idea now is to earn enough money to live as a married couple by having two incomes. But the traditional belief with respect to the roles of men and women tends to be ingrained in the minds of men. They believe that the husband needs to go out and earn money and the wife needs to protect the home. As a result, if men do not have regular employment and have a low income, they are unable to get married, causing a sharp rise in the percentage of unmarried people.

In looking at Graph 3, another problem presents itself. While 85.7% of women had regular employment before getting married, only 21.9% had regular employment after the birth of their first child. By contrast, the percentage of unemployed women, which was at 4.5% before getting married, has risen to 75.5% after the birth of their first child. In a survey on the reasons why women are unable to have the number of children they planned (Summary of Results on Survey Targeting Married Couples on Marriage and Childbirth for 14th Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2013)), the majority (41.6%) answered “age or health-related reasons.” This was followed by “unstable income” (30.5%). By comparison, 12.7% answered “lack of childcare services,” an issue that has received much media coverage. In other words, the drop in income resulting from the switch from two incomes to one, in addition marrying and having children late, is another reason why married couples are unable to have the number of children they planned (average: 2.07).

We need to create an environment that allows people to marry in their 20s and start a family

If we explore the causes of the declining birth rate from the perspective of demography, the necessary measures will become apparent. So what are those measures? We need to achieve a society in which people are able to marry by their late twenties and women are able to continue working even after childbirth, allowing married couples to have two incomes. To achieve this, we need to create a truly gender-equal society. For instance, men need to help out with household chores and raising children, and public agencies and local communities need to provide assistance with raising children. Corporations need to recognize that their decision to cut down on the number of regular jobs and increase the number of irregular jobs, a downsizing measure that was taken in a desperate effort for survival after the bubble economy collapsed, resulted in a fallacy of composition. The decision caused people to remain unmarried, to marry late, or to have children late, which caused the market to become smaller due to the decline in population. I would like corporations to take steps to transform their employment and labor practices such as eliminating excessive working hours and offering more opportunities to work from home by utilizing the Internet. I will continue to present such analyses and proposals to the government in blue-ribbon panel discussions carried out by the Cabinet Office for coming up with measures against the declining birth rate, and will call for measures that are truly necessary.

* The information contained herein is current as of July 2016.

* The contents of articles on M’s Opinion are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.