While major disasters occur frequently, the effects of disaster management are difficult to perceive

In recent years, a series of disasters has occurred around the world. The Philippines and Vietnam have experienced repeated large-scale floods, while Myanmar and Turkey have suffered significant earthquake damage. Floods and earthquakes have also occurred in Japan, seriously affecting the lives of local communities. The cost of damage caused by disasters worldwide is on the rise, particularly in developing countries where urbanization and economic growth are progressing simultaneously.

Disasters do not impact everyone equally. In reality, cases around the world have shown that people who are already socially vulnerable, such as the elderly, women, persons with disabilities, the poor, and ethnic minorities, are more likely to suffer and be left behind in recovery.

In the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, more than two-thirds of the people who died were aged 60 or older. People who had difficulty evacuating were particularly vulnerable. Data from Miyagi Prefecture indicates that the mortality rate of disabled residents was about 2.5 times the overall average.

In addition, disparities in housing conditions also cause uneven damage. Low-income households and students who live in old wooden houses with low rent are more likely to suffer from house collapse due to earthquakes. This phenomenon, in which the social structure of normal times is directly reflected in the distribution of damage during emergencies, is described by the concept of disaster-vulnerable groups.

In order to reduce this disparity, it is essential to first improve the disaster management capabilities of society as a whole. Public policy plays a significant role, and there are many measures to reduce damage, such as making houses earthquake-resistant, improving infrastructure, disseminating disaster management information, and strengthening the disaster management capacity of local communities.

In the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake, over 6,000 buildings were completely destroyed and over 18,000 were partially destroyed. Many of the collapsed houses were built under the old earthquake-resistance standards before 1981, and it is reported that there was very little damage to the buildings complying with the current standards after 2000. This case can be seen as demonstrating how earthquake-resistance standards are effective in reducing damage.

On the other hand, many developing countries lack the capacity of government agencies to implement the earthquake-resistance standards effectively. In poorer countries, investment in urgent issues such as education, health care, roads, and water supply tends to take precedence over disaster management, and preparation for unpredictable disasters takes a backseat. This problem also symbolizes the difficulty of policy choices.

Another structural challenge is that the effects of investment in disaster management can be hard to visualize. Even if levees and dams are built, it is difficult to tangibly feel that they prevent damage unless a disaster occurs. If a flood did not occur because of the existence of levees, the contribution would not be visible, and doubts are likely to arise about whether the effect was worth the cost. The debate over so-called “super levees” is a prime example of this.

The national and prefectural governments announce the cost effectiveness of flood control projects, but it may not reach the general public sufficiently. Government organizations need further efforts to disseminate information.

How to spread the knowledge of disaster management from a disaster-prone country to the world

In the Great East Japan Earthquake, a massive earthquake triggered a tsunami, which in turn led to a nuclear accident, large-scale fires, industrial complex fires, and even the disruption of international supply chains, resulting in unprecedented, massive, and complex damage.

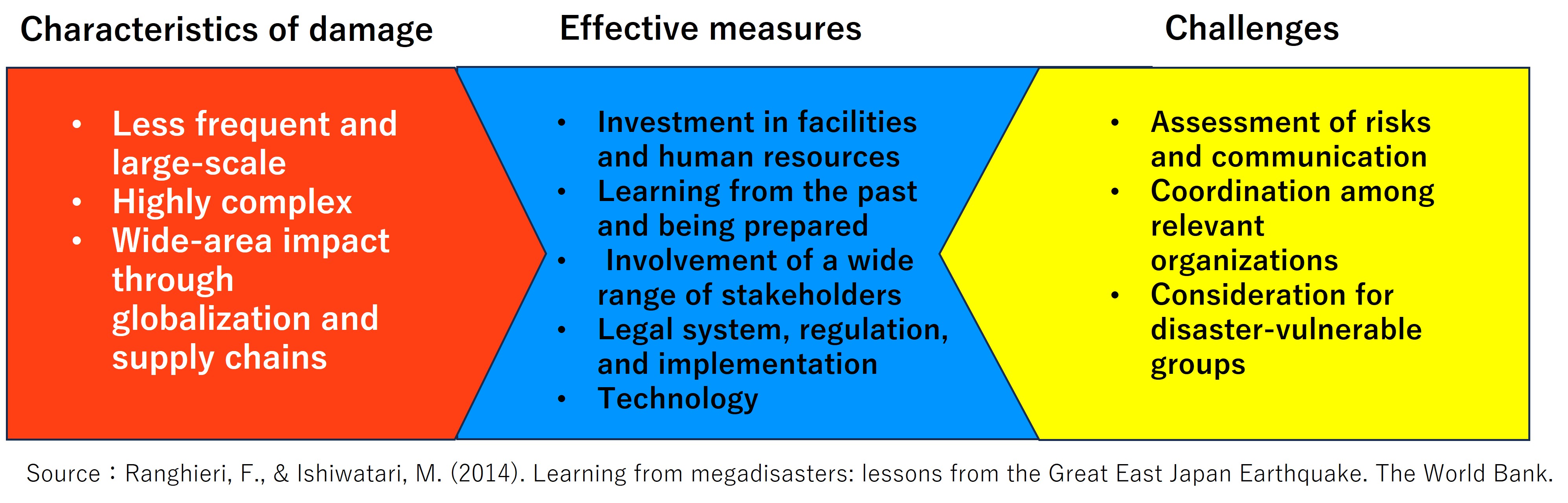

The World Bank report, Learning from Megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake, which I led in preparing, organizes the characteristics of the damage caused by the disaster, effective measures, and future challenges. The report assesses that although the damage caused by the earthquake was enormous, the disaster management system that Japan has accumulated over the decades had performed a certain function, and to some extent contained the spread of damage.

Specific initiatives include investment in robust structures such as buildings and coastal levees that use advanced technology. Furthermore, developing methods for scientific analysis of disaster risk, improving the accuracy of weather and earthquake observations, and enhancing warning systems and hazard maps have long been addressed. In addition, earthquake-resistance standards have been revised each time a major earthquake occurs, and have evolved into stricter and more effective ones. Japan is also characterized by its regular disaster drills at schools, companies, and government buildings, which have taken root as part of the culture.

On the other hand, there are still many challenges. First, the methods used for disaster risk assessment and their limitations are not fully shared with local government officials and residents. In addition, cooperation among the national government, local governments, and the private sector does not always function smoothly at the front of disaster response, leaving room for improvement. Consideration for the disaster-vulnerable groups is still a major issue.

As you can see, Japan is a disaster-prone country, but at the same time it has a wealth of knowledge and experience in disaster management. Many developing countries and international organizations have expressed their interest in learning Japan’s expertise. Unfortunately, however, Japan’s insights are not fully shared with the rest of the world.

The biggest reason is that information available in English is very rare. Because insights are not systematized and are often presented piecemeal as individual examples, it is difficult for overseas researchers and government officials to grasp the big picture of Japan’s disaster management strategy.

In fact, when I give lectures in developing countries, I am often asked, “What specific disaster countermeasures has Japan implemented?” For example, Japan has continuously invested in flood control projects for over 100 years since the Meiji period. However, it is difficult to say that sufficient materials are available, even in Japanese, to demonstrate the effects quantitatively.

In addition, securing funds is essential for disaster management and raising awareness. Since the times when Japan was not economically prosperous, communities and governments have advanced disaster countermeasures by pooling their wisdom and sharing the funds. In Shizuoka and other regions, there are examples where landowners and wealthy people pooled their own funds and carried out flood control projects. There is a history of communities independently taking responsibility for disaster management.

Of course, national and local government subsidies currently play an important role. However, relying solely on subsidies is not enough. There is no doubt that local communities and the government need to share their responsibilities and roles in creating a system for responding to disasters, evacuating, and managing evacuation centers.

Cooperation in local communities that Japan should learn from developing countries

Local societies and communities play an enormous role in disaster countermeasures. When a disaster such as a tsunami or flood occurs, it is not the administration but the local people who take action first.

Volunteer organizations such as Syobo-dan (volunteer fire corps) and Suibo-dan (flood fighting corps), as well as residents living nearby, play a central role in providing a variety of support, such as rescuing people from collapsed houses, calling for evacuation, and helping to run evacuation centers. This is why it is said that the stronger the local ties, the faster the response to a disaster, and the smoother the subsequent recovery and reconstruction.

I myself have an engineering background, but there is a deep-rooted tendency that engineering specialists take the lead in disaster management in Japan. Certainly, engineering and scientific knowledge is essential for understanding the mechanism of earthquakes and eruptions, and the structure of levees and dams. However, natural science alone is insufficient to make disaster management measures actually work in society. Knowledge and perspectives from fields other than engineering and science are essential. Examples are communication to convey appropriate information to residents, social systems to protect vulnerable groups in the event of a disaster, and environmental improvements to ensure a comfortable stay at evacuation centers.

When we consider the living environment in evacuation centers, for example, what we need is a humanities and social sciences perspective rather than engineering knowledge. We must understand problems from a broader perspective that considers gender and minority issues, ensures privacy, and reduces stress for children and the elderly and propose improvement measures. I believe that there is room for rethinking the emphasis on science in disaster management. Combining knowledge and practice from various fields should enhance the quality of disaster management.

Also, a point that the government should emphasize is improving the management of evacuation centers. As has been pointed out since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, we still see many situations where people are forced to sleep together on the cold, hard floor of gymnasiums. After the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in 2024, it took two weeks to install corrugated cardboard beds, and partitions to protect privacy were also insufficient. As a disaster-prone country, I believe that Japan should prioritize this area.

Sharing Japan’s disaster management insights with the world has great significance. However, it is not necessarily true that Japan is advanced in all aspects.

In some cases, developing countries are more advanced when it comes to community cooperation. For example, in Vietnam, when a flood is approaching, people naturally call out to each other and give priority to the elderly to evacuate. It is by no means easy to do the same thing immediately in Japan, where local ties are weakening.

Local communities have the potential to be leveraged in disaster response, and how to draw out this potential is an important topic for future research. More detailed consideration is required on what kind of facilities enhance the disaster management capacity of communities and what kind of events strengthen the cooperation of residents.

My goal is to convey Japan’s disaster management expertise to the international community while also actively incorporating lessons that Japan can learn from developing countries. Disasters are a problem that transcends national boundaries, and we need to build a more resilient society while sharing each other’s strengths.

* The information contained herein is current as of September 2025.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.