It started with “shojo manga”

When I was a child I immersed myself in reading manga comic books, particularly shojo manga (“girls’ manga”). Since I started at the age of four, I think I might be one of the people with the longest history of continuously reading manga in the world. After graduating from college I began work editing books, but when requested by an outside party to review shojo manga I noticed that some transformations had become apparent in the sexuality and values of women.

To use changes in views of love as an example, one change that can be said to have taken place in the world of shojo manga from the late 1960s, when love came to be depicted in shojo manga, through today is the breakdown of the romantic ideology in which the three elements of sex, love, and marriage combined into one. For example, in the shojo manga of the past, in which the main characters were girls from countries other than Japan, love was depicted as the road to a happy marriage. This was a world in which people fell in love only once in their lives. However, over time the state of love became more diverse, as symbolized by the arrival of the words motokare (“ex-boyfriend”) and motokano (“ex-girlfriend”).

With regard to depictions of the family as well, while in the past many involved stepmothers or secret births, later the view appeared that saw the family as a place where one can be, regardless of its form and independent of blood relations. The manga came to depict happy families led by single mothers, single fathers, and remarried parents, showing characters who were not unhappy even though they had only one parent. The same changes took place with ways of depicting work. While in the past if the main character were a woman working in an office the stories would be centered on her love relations after work, today the number of manga touching on ways women can live through their work is increasing.

In these ways, shojo manga have come to express with sensitivity the values of a new generation. It is not just that the works reflect the values of their readers. Since the authors and readers of shojo manga are close in age, a succession of fresh new works has appeared through a sharing of new values between authors and readers and through collaboration between the two.

In fact, the genre of shojo manga itself is one that is nonexistent in the West. More accurately, while such comics had existed in the West through the 1950s and 1960s, after that comics came to be seen as basically a medium for boys. One of the major reasons Japanese manga have been so well accepted in the West as a fresh new genre is the way they show that it is all right for girls and women to read and write comics.

In Japan, which accounts for one-half the world comics market, manga culture is supported by magazines

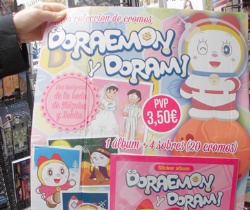

“Doraemon,” with supplements, in Spain

“Doraemon,” with supplements, in Spain  A magazine kiosk “東方書報亭” in Shanghai, China

A magazine kiosk “東方書報亭” in Shanghai, China

In April 2008, I was appointed an associate professor in the new School of Global Japanese Studies at Meiji University. At that time the main subject of my studies was the international comparison of comics. I had first started looking at overseas comics even earlier, around 2002. This was inspired when I learned at a symposium held in the Kansai region that Japanese manga were undergoing a massive boom in popularity in Europe. I became even more interested when I saw how the way manga was accepted varied even among the countries of Europe, and how this was deeply related to the comics culture already present in each country. Over the past several years, I have made numerous trips oversees to Europe, Asia, and the Americas to study the comics culture and the state of manga in each country. Some interesting facts include the way “Doraemon” is very popular in Asia but has not been well received in Europe, outside of Spain. The same is true of “Slam Dunk.” In these ways, the popularity of an individual manga varies with the culture of each country to which it is exported.

In fact, Japan’s manga market accounts for about one-half the world comics market. Thus, the country of Japan has a market roughly equal in size to that of the entire rest of the world. Analysis of the background of how this market grew so large brings into view Japan’s own unique manga culture. For example, it probably would be no mistake to say that there is not a single person in Japan who can claim never once to have read a manga. Also, people in Japan expect to be able to buy manga at bookstores. However, selling comics in bookstores is not such a common practice around the world.

One of the most distinguishing characteristic of the Japanese market is the way 99% of manga are first serialized in magazines and then collected later in book form. This is not the case in any other country. Through serialization in magazines, the content of manga can change depending on how readers respond. In other words, in Japan manga are a medium created together with readers. In this relationship, it is clear that manga editors, who serve as a connection between readers and authors, play an important role. Also, in other countries comics exist basically as works that are either bought by parents for their children or intended for adult readers from the start. In either case, the buyers are adults. But in Japan, children buy them with their own pocket money. That is, authors supply directly to readers works created to be ones that children, particularly adolescents in middle school or high school, will want to read. What’s more, since they are serialized in magazines they draw out the reader’s interest through use of cliffhangers.

Although in Japan the authors of manga tend not to recognize the importance of magazines to this degree, it should not be forgotten that the content-distribution medium of the magazine has had a major background influence on the independent development of Japanese manga. Both authors and readers should recognize anew the extreme importance of magazines in Japan’s manga culture, including the fact that while most comics in other countries tell self-contained stories, most in Japan are serials, and the fact that without magazines it would be difficult for new authors to arrive on the scene. While today magazine readership is decreasing gradually, I believe that too-readily abandoning this medium would be likely to undermine the existence of Japanese manga itself. It may be the time for both readers and authors to rediscover the attractions of the manga magazine format before it disappears.

Promoting international exchange through comics

The Angoulême International Comics Festival in France

The Angoulême International Comics Festival in France  Lucca Comics & Games in Italy

Lucca Comics & Games in Italy

Today, it is a fact that Japanese manga are popular and widely read around the world. While one view holds that the main reason for this popularity is the fact that Japanese manga are very interesting to readers, when we recall the examples of “Doraemon” and “Slam Dunk” this view would seem too simplistic. We need to look at how factors already present in each country, such as its comics culture and distribution conditions, affect the acceptance of manga from the background, rather than simply crediting their popularity to the content of manga alone.

For example, the status of comics varies even among countries within Europe. While in France comics are considered the “ninth art,” well-recognized in society and read widely, in neighboring Germany, a country that gives priority to the printed word, pictorial descriptions are considered uncultured, and comics are thought of as part of low culture. For this reason, for the most part Germany has never developed its own comics culture, and in this unexplored territory Japanese manga have captured the interest of female readers, who account for roughly 70-80% of manga readers in Germany. In ways like this, conditions of the manga market vary by country. As another example, in the Americas, most countries of Asia, and even many European countries comics usually have been sold at newsstands, and it has been rare for them to be sold in bookstores like they are in Japan. The breakthrough for Japanese manga in the United States, where manga culture had found it difficult to take root, began with organized efforts to sell manga in bookstores, counter to common practice in that market.

Expanding something from one country to another requires knowledge of the other country’s culture. However, in the case of manga Japan can be described as being in an isolated state, like the Galapagos Islands. While in the cases of literature and music it would be impossible to imagine a world without foreign literature or foreign popular music, at places where manga are sold nearly all the works available are Japanese manga. Even so, there is in fact strong mutual influence at an international level among authors.

One event played a major role in demonstrating this fact. In 2009, a symposium was held at Meiji University, organized jointly with Kyoto Seika University, to which the comic artist Moebius, a leader in the genre both in France and around the world, was invited. Thanks to his science-fiction works with their amazing artwork and worldview, Moebius has had a strong influence on artists worldwide. Even in Japan, he strongly influenced artists such as Hayao Miyazaki, Katsuhiro Otomo, Taiyo Matsumoto, and Naoki Urasawa. This symposium at Meiji University featured a session to which Naoki Urasawa and the manga columnist and Gakushuin University graduate school professor Fusanosuke Natsume were invited. I believe that this symposium, which attracted so many attendees that they could not all fit in the Academy Hall, which has a 1,200-person capacity, proved a valuable opportunity to think about the relationship through which Japanese and European comics influence each other. It led to the start of the International Manga Fest, and since then comics from overseas have gradually come to attract more attention in Japan. Furthermore, Meiji University plans to open an international manga museum in the near future, and I would like to continue playing an active role in promoting international exchange through comics in the future as well.

I think that looking at comics from overseas, not just Japan, also can have the reverse effect of leading us to think about what are the distinguishing features of Japanese manga. I encourage readers to take a look at comics from overseas. They just might discover something new.

What’s missing from “Cool Japan”

In recent years, developments such as the spread of the Internet have led to continual changes in the media environment. In today’s age readers can find manga on the Web, but in light of the importance of magazines to Japanese manga it is not the case that the genre simply can be transferred to the Web unchanged. There is a need to adapt to changes in the media environment while keeping the role of magazines secure.

One subject of concern amid these circumstances is the issue of “scanration.” This term refers to an act of digital piracy in which people scan original manga, translate their text, and then unlawfully post the resulting works to the Internet. A similar practice that involves distributing works of animation with translated subtitles is called “fan-subtitling.” While this began as a true fan-centered activity, and at times the unauthorized copies have disappeared from the Internet when an official translated version was released, recently more malicious organized activities have spread, centered on the U.S., in which such files are collected automatically and then illegally published on websites that earn money from advertising. As a result, manga sales in the U.S. have fallen by one-half. The sound growth of the manga industry requires that measures be taken promptly to address such illegal websites. For example, one effective means of preventing unlawful uploading of copyrighted content is for the original publisher to translate the work and publish it worldwide at the same time. But there are limits to what a single company can accomplish. I believe that there is a need for a strong international protest against piracy and for support from the government of Japan, including subsidies.

In addition, there is a problem with the export of Japanese manga overseas itself. Around the world people have pointed out that Japanese publishers are slow to license their copyrights. What’s more, local publishers who have secured rights to use copyright need to obtain permission separately in Japan each time they use illustrations from a work in their advertising or in staging events, and often they do not receive prompt replies to their requests for permission. In contrast, companies like Disney prepare numerous packages of illustrations that can be used in products or promotions, making these available for use immediately through simple procedures. Japan too should learn from such an international strategy.

While the same is true of the efforts under the “Cool Japan” strategy, Japan’s manga exports seem to employ only a unilateral, monolithic approach based on the belief that interesting manga can be certain to sell, and that promotional activities alone are enough to sell them. The recent efforts to promote Japanese cuisine adopt the same approach. But I believe that there are many areas where Japan could make further efforts. These include understanding the cultures and distribution systems of foreign markets from many different points of view and thinking of strategies to fit them, in order both to strengthen the brand power of culture and to make it easier to use, as well as countering piracy and unlawful use while also securing terms for bartering, and, from the opposite point of view, giving partner publishers in other countries greater freedom to use content in their own promotional activities. I think that doing so would lead to the creation of a virtuous circle in both culture and industry, through mutual understanding with other countries.

* The information contained herein is current as of April 2014.

* The contents of articles on M’s Opinion are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.