Value-added taxes have been adopted in more than 150 countries

In April 2014 the consumption tax was raised for the first time in 17 years to 8%, with another tax increase to 10% slated for the fall 2015. With consumption taxes the tendency is to focus only on the tax rate, yet there are numerous problems on the structure of the Japanese consumption tax that was adopted 25 years ago. I worked at the National Tax Agency for a long time before taking up my post at this university and was deeply involved in the Japanese tax system, including tax reform geared towards the adoption of a large-scale indirect tax. In light of this experience I would like to point out the problems on the Japanese consumption tax. To start with, I would like to clearly spell out a definition of just what a consumption tax is in the first place.

A consumption tax is a type of indirect tax. As opposed to direct taxes wherein the taxpayer and tax bearer (person on which the tax is imposed) are the same, such as with individual income tax, corporate income tax, or inheritance tax, with indirect taxes such as the liquor tax, tobacco tax, and consumption tax the taxpayer and tax bearer are different. Of these indirect taxes the liquor tax and tobacco tax are excise taxes, whereas the consumption tax is a general tax that targets all goods and services except for those that are tax exempt.

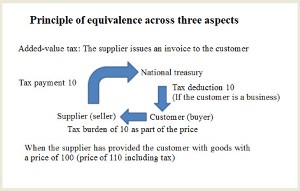

Ultimately it is a tax that is borne by consumers, and since the taxation base is broad and cascade taxes are done away with it, the system has the unique feature that taxes concerning the purchase stage can be deducted. Due to the advantages such as impartiality, neutrality, and stable tax revenue, it has been introduced so far in more than 150 countries as core items of taxation that support their governments’ tax revenues. In other countries besides Japan such a tax is oftentimes referred to as a value-added tax (VAT) or a goods and services tax (GST), with this tax only referred to as the consumption tax in Japan. Japan’s consumption tax is one form of a value-added tax, but it differs in several ways from the value-added tax that has been adopted in the EU. I would like to consider some of the problems with the Japanese consumption tax by investigating the EU-style value-added tax.

Differences between the invoice method and the account method

In the 1950s France invented the value-added tax structure and led the world in adopting such a scheme, after which such schemes were adopted one after another in various European countries from the latter half of the 1960s through the first half of the 1970s. The backdrop to its adoption lay in the necessity to resolve conflicts concerning international coordination over indirect taxes with a view towards the intra-regional economic integration of the European Economic Community (EEC; currently the EU) and the creation of a joint market. A value-added tax was regarded as the optimal structure in order for Europe to function as a single market and to achieve fair competition within countries and within the region.

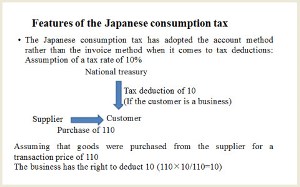

One basic structure for a value-added tax is one in which the tax amount related to purchases is deducted from the tax amount related to sales in order to avoid cascading taxes. This method of securing tax deductions in an institutional sense comes in two types: the “preliminary stage tax deduction method (invoice method)” adopted by the EU member countries and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member counties (except for Japan and the United States), and the “purchase tax deduction method (account method)” that has only been adopted by Japan out of the OECD countries.

The “invoice method” refers to a scheme whereby the amount of taxes to be paid by a business is calculated based upon invoices (transaction vouchers with the tax amount clearly specified) related to individual transactions. Specifically, the value found by subtracting the total tax amount listed on invoices related to purchases from the total tax amount listed on invoices related to sales serves as the tax amount to be paid. The invoice method boosts transparency and makes it difficult to give rise to improprieties.

On the other hand, the “account method” refers to a scheme whereby the amount of tax to be paid by a business is calculated based upon books of account. The total amount found by multiplying the tax rate against the purchase amount listed in the books of account is subtracted from the total amount found by multiplying the tax rate against the sales proceeds listed in the same books of account, with this figure serving as the tax amount to be paid. One problem with the account method is that a portion of an amount equal to the consumption tax borne by the consumer remains with the business. In other words, non-negligible omissions occur in the collection of taxes, so it would have to be described as a structure that falls short in terms of transparency. Checks to confirm whether the business paid its taxes must be made, which is why some consider it essential that the invoice method be adopted.

Problems with electronic transactions, reduced tax rates, and tax exemptions

In considering how to structure taxation for cross-border electronic transactions, it becomes apparent that the invoice method must be adopted. For example, one example of cross-border electronic transactions that could be raised is the supply of electronic books from businesses in different countries to consumers in Japan over the Internet. In cases where such businesses in other countries do not maintain any sort of facilities within Japan it will be difficult to get a grasp of their electronic transactions, and so therefore taxing them will be difficult. Conversely, as things currently stand it would be extremely difficult to demand that the consumers pay taxes on these. Moving forward, structures for imposing taxes on cross border electronic transactions will have to be formulated through international cooperation. In doing so, it goes without saying that it would be preferable if the value-added tax structures in different countries were uniform. In this sense as well, the introduction of an EU-style invoice method will be sought from Japan.

The debate has moved forward over the application of “reduced tax rates” for food and other daily necessities in order to mitigate the regressivity (when the proportion of the tax burden grows larger the lower one’s income is) in the wake of increases in the consumption tax, but there are no shortage of points that should raise concerns with their adoption. Decisions on tax rates and their applicable ranges would grow complex and arbitrary, while tax accounting would also become complicated. Above all else, the fact that the adoption of reduced tax rates would cause the loss of enormous sums of tax revenue, which would necessitate separate tax increases, is conceivable. There should be a single tax rate in order to preserve the consumption tax’s neutrality with regards to the economy, as other measures are certainly possible when it comes to dealing with regressivity.

It is a principle of value-added taxes (consumption taxes) that they are imposed on all goods and services. However, goods and services that people are not inherently used to seeing consumption taxes on (land transfers and rentals, financial transactions) and those that require political considerations (such as medical care or education, etc.) are considered to be “tax exempt.” But I am of the opinion that no items should be tax exempt. When tax exempt sales are carried out, tax deductions for the consumption tax included within the good or service sold are not recognized; and consequently this produces duplicate taxation in cases where the purchasers of tax-exempt goods and services are businesses on which taxes are imposed. The fact that the businesses that mainly undertake tax-exempt sales cannot accept the purchase tax deductions inevitably gives rise to unfairness and inconvenience in economic transactions. Tax-exempt structures could potentially disrupt outstanding arrangements with value-added taxes built into them.

Making the tax system more transparent and rational

Thus far I have pointed out several of the problems on the Japanese consumption tax. When there are deficiencies in how the tax system is structured this can generate distortions for the economy and unfairness in terms of taxation, which in turn can potentially serve to magnify discontent among the public. While the claim could be made that value-added taxes, which include consumption taxes, have been the most successful tax system in the latter half of the 20th century, this is not to imply that we have at long last arrived at their culmination. The EU and other countries from around the world are undertaking a considerable number of examinations geared towards achieving even more exceptional tax systems. Based on the recognition that Japan’s consumption tax is still developing, we must achieve an impartial structure for it in order to advance to an indirect tax that is more neutral, efficient, and effective.

One of Japan’s greatest challenges is its enormous budget deficit and cumulative debt. Unless such problems are resolved Japan’s future will be considerably gloomier. The consumption tax is regarded as a means of deliverance for resolving such problems, but it is no doubt widely understood that it cannot serve as a means of deliverance at the level of 8% or 10%. I believe that starting from next year onwards Japan will enter an era in which it will have to increase its consumption tax in a step-wise manner. Given such circumstances, reforms will be needed to make the structures more transparent and rational. As such, this requires that everyone among the public have an awareness of the issues concerning the logic and structure behind the consumption tax.

* The information contained herein is current as of March 2014.

* The contents of articles on M’s Opinion are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.