A society where being monitored by camera is taken for granted

I conduct research on the relation between organizations and humans from the sociological perspective. It can be said that we who live in our time are almost always monitored in one way or another, in various situations, such as in the highly advanced information society, the organization that we belong to, and communities.

Surveillance may be associated with prisoners that are watched by wardens. However, map apps on smartphones that communicate location information are also a form of surveillance. It is also impossible to do a little shopping outside the home without being captured by surveillance cameras under the name of “crime prevention cameras” that are everywhere in towns.

According to one account, it is estimated that there are more than 5 million crime prevention cameras installed in shopping streets and stations in Japan. Some statistics show that the number of these cameras is ranked 5th in the world. In addition, cameras that are personally installed at home, etc., and monitoring in factory lines can also be counted as surveillance cameras.

Moreover, dashboard cameras almost amounting to the number of cars are recording streets. We can also assume that each of us carries a camera owing to the spread of smartphones. Thus, it is safe to say that the substantive number of surveillance cameras is larger than the total population, and society being recorded all the time is taken for granted.

Now, if it claims to be a crime prevention camera, it should be a camera which actually prevents crime. However, as typically shown on TV news programs as footage of the moment when the crime was committed, captured by a crime prevention camera, in reality, it is merely recording crimes that were already committed.

Surely, it is beneficial that the footage is helping with the arrest of perpetrators. However, for the purpose of crime prevention, crime prevention cameras in fact may not be as effective as we have hoped.

In fact, according to multiple studies on crime prevention cameras, although they have some deterrent effect against littering and theft, their effect is limited against violent crimes such as assaults and injuries, and felonies such as murders. Moreover, it is considered that they have almost no deterrent effect against crimes for which perpetrators do not care about being arrested, such as indiscriminate murders and assaults.

So, how do we feel about Japan’s public security? According to the survey conducted by the Cabinet Office from December 2021 to January 2022, to the question asking, “Do you think that current Japan is a country with good public security and that you can live safely and peacefully?” 85.1% of the respondents answered, “I think so” or “I tend to think so.” Given that there is no society that is completely safe and peaceful, this is quite a high figure.

On the other hand, to the question asking, “Do you think that the public security of Japan has improved in the past decade, or do you think it has become worse?” as much as 54.5% of them answered, “I tend to think that it has become worse” or “I think it has become worse.”

In the previous survey conducted in 2017, 60.8% of respondents answered, “I think public security has become worse.” From this, maybe there was a minor improvement. However, in a society where about five out of six people think that it is safe and peaceful, three out of six people are feeling that public security has become worse in the past decade. We call this a “degeneration of perceived security.”

Why is the perceived security bad while the number of crimes is decreasing?

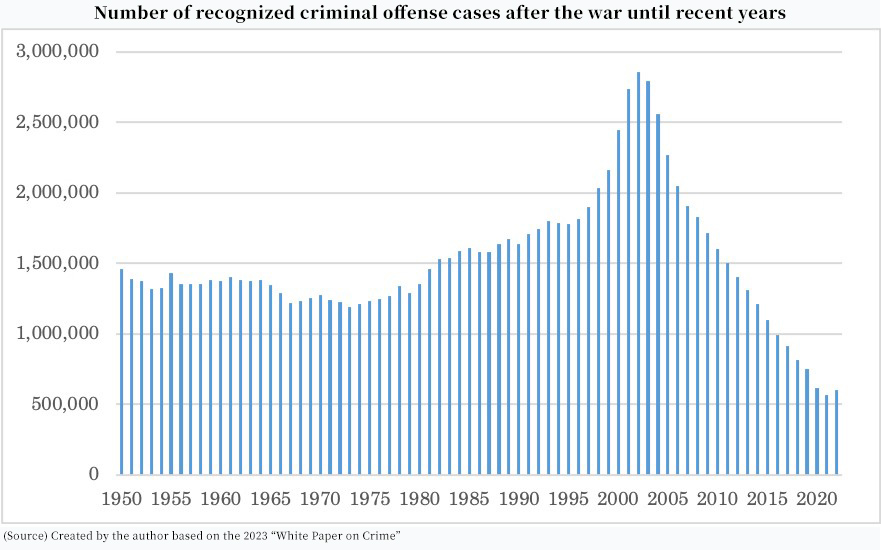

However, is public security indeed degenerating? Statistically, we cannot say so. According to the National Police Agency, the number of annual recognized criminal offense cases dramatically decreased after peaking in 2002 (about 2.85 million cases). Although in 2022 the number (about 600,000 cases) increased from the previous year for the first time in 20 years, the number continues to be the lowest level since the start of collating statistics.

In the past two decades, the number of surveillance camera installations has increased for sure, and their functions such as resolution must also have improved. Nevertheless, why are we living with the anxiety that our public security is deteriorating day by day?

Various factors can be considered to be causing the degeneration of perceived security. One of them is the crime reports that repeatedly appear in the media, such as TV and internet.

In an advanced information society, the total amount of information becomes very large. Reports are shared and commented via social media, and information on sensational crimes will expand in quantity. Moreover, when a new type of crime, such as so-called illegal part-time working or cyber crime, appears, people think that the reports are “the tip of the iceberg” and they tend to estimate that there are more criminal cases than the actual number of cases.

Also in quality, owing to the increase of visual news that is more impactful, a more vivid impression is conveyed. It is considered that such change of information in volume and quality is causing the degeneration of our perceived public security.

In other words, despite the fact that public security is improving, people are afflicted by the degeneration of perceived public security and in pursuit of a more peaceful and safe society, and they dream about improving surveillance technology, including surveillance cameras.

Owing to the existence of anxiety, the technology to prevent a crime from happening is justified. However, because of the fact that such technology still cannot eliminate crimes completely, people’s anxiety is furthermore stirred up. Such a negative cycle seems to have been established.

As such, in a society where legitimacy is attached to surveillance, surveillance technology being introduced is taken for granted even in familiar organizations and communities, and in front of such cameras, everyone will be treated as a person who might commit a crime some day or namely, a potential suspect.

So, the anxiety that could not be removed by the surveillance technology is generating a mutual surveillance society = mutual distrust society where we monitor each other, or in other words, treat each other as a potential suspect.

A typical example showing the situation that a person is exercising vigilance against another, rather than trusting another, and mutual surveillance is normalized, can be people’s behavior concerning so-called suspicious individual information.

Nowadays, “suspicious individual information” is immediately sent via e-mail or posted on websites by the police and municipalities. For example, the following was stated:

– Around 5:40 p.m., a man talked to (female) children when they were passing by the street of XX 3-chome.

– Content of the interaction, etc.: “You guys. I have some treats for you.”

– Information on the suspicious person: About 70 years old, about 160 cm tall, gray hair, black suit, sunglasses, holding a clutch bag

Of course, we can only imagine to some extent from what is stated. However, in this case, it could be that an old man simply tried to give children some candies that he had. Even such fragmented information without context, if it is verbalized as “suspicious individual information” sent by the police and municipalities, it starts carrying some kind of quasi-objectivity and arouses the impression of a suspicious person who tried to commit a crime.

Vulnerability of communities where a person talking to someone is regarded as a suspicious individual

This is not to say that I am claiming that all the so-called “suspicious individual information” is irrelevant. Rather, I am pointing out the fact that among the possibilities that could be anything, the situation of suspecting each other as a potential suspicious individual is taken for granted and unconsciously being selected as the only option.

Here, a common individual is reporting a potential suspicious individual from the standpoint of a well-intentioned reporter based on a subjective judgement. Whether the person is a real suspicious individual or not is sidelined, and if the person is suspicious even at the slightest (or even if the person is not suspicious), people report them under the name of “prevention” while fearing disputed suspicious individuals who were reported by some other people, and, as a result, people strengthen their perception that public security is deteriorating and enhance mutual surveillance furthermore.

This is not an armchair theory. In fact, in the 2000s, triggered by the incident in which a girl was abducted and murdered, a municipality established an ordinance to restrict talking to children. In the 2010s, a post made by a reader of a newspaper in Kansai region, saying that in a condominium building, the residents’ association decided to prohibit greetings caused a buzz.

In such a community which relies on the possibility of “a person talking to someone = a suspicious individual” in society, even if a child is crying in the park, perhaps they cannot help but hesitate to ask “what happened?” to the child. As a result of preventing the potential suspicious individual, there could be a situation in which people cannot help a child who is really in trouble.

In my view, a society of mutual surveillance and mutual distrust exposes its vulnerability, especially during disasters such as massive earthquakes. When a massive disaster occurs, public services such as firefighting and emergency services will become limited. Thus, it will be necessary to help each other in the community. As I myself suffered from the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I know about it well from my own experience.

For example, in such circumstances, can residents help each other in collective housings where they are not allowed to talk to children, or in condominium buildings where greetings are prohibited? As a result of trying to excessively prevent a crime, aren’t they being put in a situation where they are not prepared for an unprecedented disaster?

In our time, regardless of whether we are conscious of it or not, various surveillance technologies are becoming routine. Especially among young generations, many do not have so much aversion to surveillance cameras and mutual surveillance communities, and prioritize the convenience and comfort of technology.

However, our society, which exists together with surveillance technology, does not only have safety and convenience but also lurking factors of anxiety, distrust, and inconvenience, and the risk may surface in an unexpected situation. Are such societies, organizations, and communities indeed healthy? I would like you to think about it too.

* The information contained herein is current as of May 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.