Amazon’s strengths: Inventory management and in-house distribution system

For companies that sell goods, production and operations management tasks, such as adjusting production and inventory of products to meet market demand as well as procuring raw materials in an optimal manner, are very important for achieving long-term profits.

For example, one of Amazon’s strengths is its excellent inventory management. As of 2024, Amazon Japan has 27 fulfillment centers (distribution hubs) and more than 50 delivery stations (delivery centers) in Japan, supporting an overwhelming in-house distribution system that enables same-day delivery.

When we shop on e-commerce (EC) sites like Amazon, we even feel like all kinds of products can be produced immediately with just a click, and they’re delivered to us instantly. However, from the perspective of production and operations management, we should never forget the fact that manufacturing always takes time.

The manufacturing of products, such as the smartphones we have, starts with the procurement of raw materials and the production of parts, which are assembled and processed into finished products, and then they are delivered to retail stores through the distribution network. In the case of EC, products do not directly go through retail stores, but even so, the time required for production and transportation cannot be reduced to zero in the case of “things of weight and shape.”

This continuous manufacturing process is called a supply chain. In relation to it, the management method to control the overall flow, ensuring smooth operations, is called supply chain management (SCM).

Today, the supply chains of various products are intertwined in complex ways across multiple countries and regions, and the number of players involved is growing. It can be defined as a long relay race, where you cannot finish if even a single runner is missing, and baton pass skills should greatly affect the company’s competitiveness.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020, disrupted supply chains around the world and caused extensive damage to the production of various products. In addition, natural disasters such as major earthquakes often cause supply chain disruptions.

In order to prepare for such a situation, it is necessary to understand the current state of global SCM and how it works. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, some people have been calling for the return of manufacturing to domestic locations, but even if this is possible, we should carefully consider how it would affect the competitiveness of companies.

Toyota’s global supply chain management

So, what are the issues when trying to execute SCM in the first place? The keywords are “time” and “forecast.”

The time required to actually make a product and deliver it to consumers is called lead time. Without a completely made-to-order situation, each company begins its activities by forecasting future demand with the required lead time.

But in reality, forecasts do not always come true, including unforeseen events like COVID-19. If there is more demand, companies will run out of stock and lose sales opportunities. On the other hand, if there is less demand, extra inventory will be stuck somewhere.

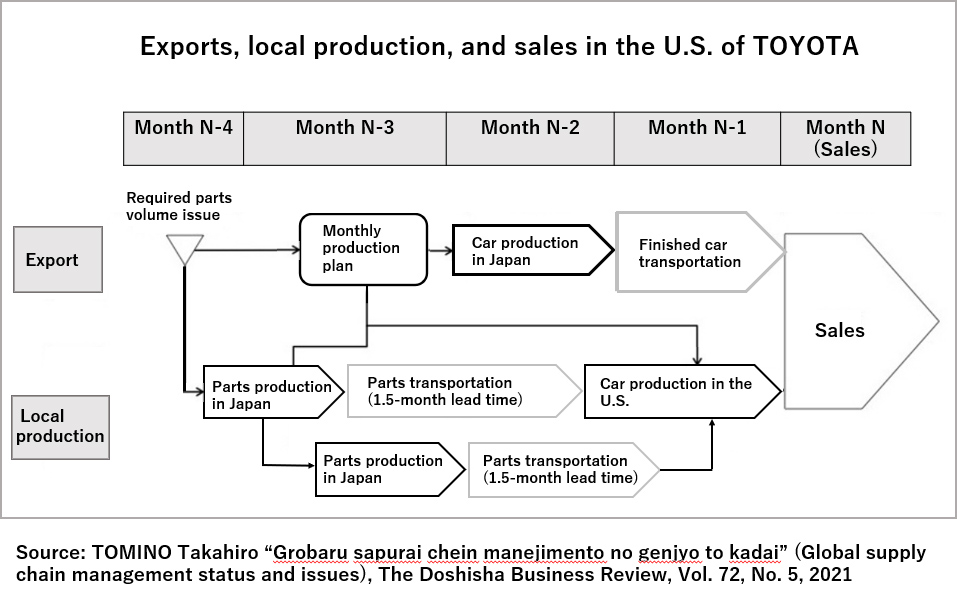

And when it comes to a global supply chain, the lead time to market supply increases rapidly depending on the situation. As an example, let’s look at Toyota’s SCM by production and sales type.

First, in the case of domestically completed cars that are produced in Japan and sold in Japan, the average lead time from the dealer’s order to delivery is about one month. However, the production plan is established one month before the production starts, and preparations, including parts procurement, are made based on the plan, so each player in the supply chain starts working earlier.

Next, in the case of export-sales-type cars that are produced in Japan and sold in the United States, the lead time becomes considerably longer. There is a process where a sales control company in the United States consolidates orders by taking into account sales results and demand forecasts in each region. After production is complete, it takes at least a month to ship finished cars. So, the lead time from local orders to delivery is approximately three months.

Then, what is the lead time for overseas-production-type cars that are produced and sold in the United States? You might think that the lead time will be shorter because there is no sea transportation of finished cars from Japan. In reality, however, it is about three months, almost the same as that for export sales cars, or sometimes longer.

One of the factors is parts procurement from Japan and other regions. For example, many hybrid-related and drive-train components are still produced centrally in Japan and must be shipped by sea. The reasons for production in Japan include challenges with quality control and production technology, and cost reductions through production consolidation. In the case of an industry as broad-reaching as the automotive sector, moving the supply chain is easier said than done.

Each player in the supply chain operates on the assumption that this lead time exists, so if you slam on the brakes, you can’t stop the whole thing right away. On the other hand, the same time lag occurs when you step on the accelerator. The difficulty with global SCM is that the response is inevitably delayed like this pedal operation.

Strong point of Zara’s and Uniqlo’s SCM

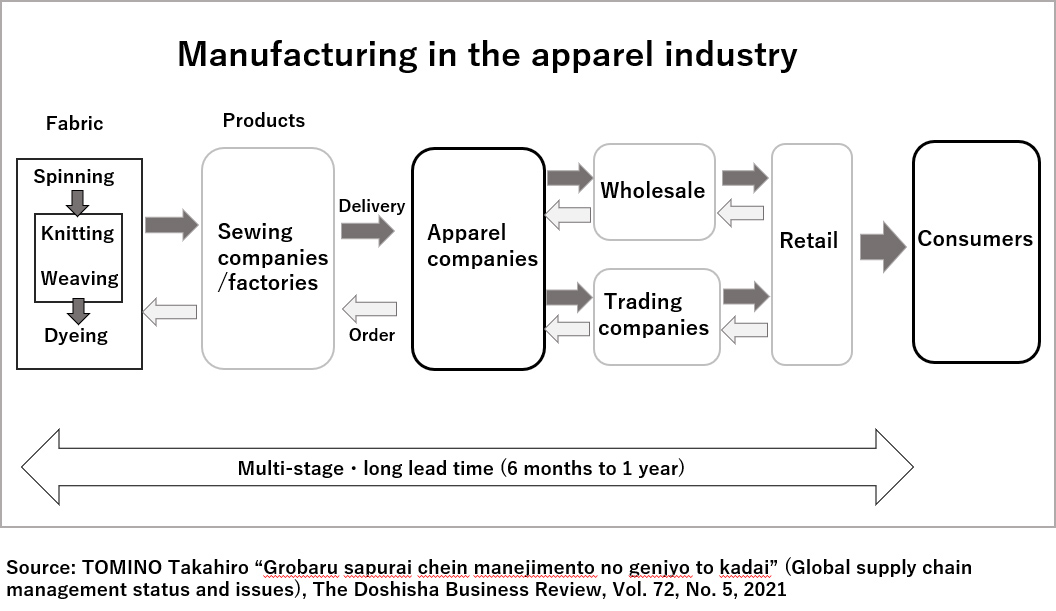

Generally, longer lead times are more difficult to forecast and increase the risk of missing items and inventory problems. In particular, apparel products, which are greatly affected by climate and trends, have long required the establishment of SCM systems capable of responding swiftly to the market.

However, not many manufacturers succeed in this. The apparel industry has a multi-stage and complex supply chain, from upstream spinning and yarn production, fabric manufacturing, dyeing, accessory manufacturing, sewing, planning and design, involving manufacturers, trading companies and wholesalers, and retail, so the overall lead time averages from six months to one year. In other words, as an industry structure, the production has to be based on forecasts.

Conversely, companies that are able to cope with this contradiction of responsiveness and long lead times can gain a competitive advantage. Let’s take a look at two top-selling companies in the global and Japanese apparel markets.

The first company is Inditex, a Spanish company known for its ZARA brand. With a very short lead time of as short as three to four weeks from planning to in-store delivery, the company realizes simultaneous reduction in missed sales and inventory through product launches on a short cycle, identifying market trends during the season. It’s literally fast fashion.

One of the features of its SCM is the use of different production sites depending on the product. The production bases are divided into Europe, including Spain, where the headquarters is located, and Southeast Asia. All finished products are aggregated in Spain, where they are shipped by plane and truck to stores around the world. In particular, products requiring a short supply chain, such as highly fashionable items, are manufactured at factories in Spain and neighboring countries.

On the other hand, relatively easy-to-forecast demand clothes, such as sweaters and T-shirts, are manufactured at low cost in remote Southeast Asia. They skillfully combine shorter supply chains, which incur higher costs but respond promptly to actual demand, and longer supply chains that produce other products steadily at a relatively slow pace.

The second company is Fast Retailing, one of Japan’s top companies offering the Uniqlo brand. The essence of the company’s SCM lies in its LifeWear (ultimate everyday wear) concept.

They focus on basic items for which demand is easy to read, and develop standard products such as HEATTECH that can be sold to everyone for a long time, and produce them at low cost mainly at contract manufacturers in East Asia. In the apparel industry, which is always swayed by trends, it is a kind of reverse thinking.

In terms of production, although inventories are adjusted on a weekly basis through changes in production plans and flexible price revisions, the lead time is about a year, like general apparel products. Therefore, Uniqlo is not a fast fashion brand and has a strong commitment to quality. In fact, when I did research at apparel manufacturing factories around the world, a representative said, “Uniqlo’s quality requirements are far higher than those of western companies.”

Ability to stand up in time of disaster

In any case, global SCM must always face the fundamental problem of “manufacturing takes time, the forecast can inevitably be wrong.”

Having said that, how do we protect the supply chain from natural disasters and conflicts? In my opinion, we should be cautious about taking measures such as adding extra inventory and easily diversifying suppliers in preparation for unforeseen types of events.

First of all, although diversifying the supply chain to avoid concentration of suppliers in a specific region is easier said than done, it is a practical challenge in the global supply chain. There are many cases where only one company can meet the quality required even for a small part.

In addition, spreading suppliers widely across multiple countries and regions increases the likelihood that costs will simply increase. If the competitiveness of the supply chain declines by short-term responses that go beyond economic rationality, it just does not make any sense.

What I would rather be aware of is how quickly we can restore supply chains when they break. After the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, a semiconductor manufacturer’s factories were damaged and the supply of microcomputers for automobiles was cut off. The Japanese automobile industry provided support by injecting its inherent capability for on-site improvement, and as a result, the restoration process was accomplished in 3 months, what was initially expected to take more than 10 months to recover. More important than not falling is the ability to stand up. Even in skiing in winter, I believe many people remember that the first thing they learn is how to get up when they fall.

To recover quickly, of course, we need to know where the damage is. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many manufacturers seemed to inspect their business partners with direct and indirect transactions at a deep level. Toyota, for example, built a supply chain database, RESCUE, in collaboration with Fujitsu after the Great East Japan Earthquake, and it is believed that the visualization of information on a vast number of parts and suppliers contributed to the recovery of production during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Manufacturing is an extremely laborious and time-consuming process in which many players take orders, transport, process, assemble, ship, and deliver products to customers. Robots do not do everything, and people are always involved in the field.

In this age of IT and digital content, it seems that consumers are less aware, but we need to remember that there is diligent and hard work behind what we get. This is why we at research and educational institutions want to convey that the world of manufacturing is interesting.

* The information contained herein is current as of July 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.