Joint custody will not solve everything

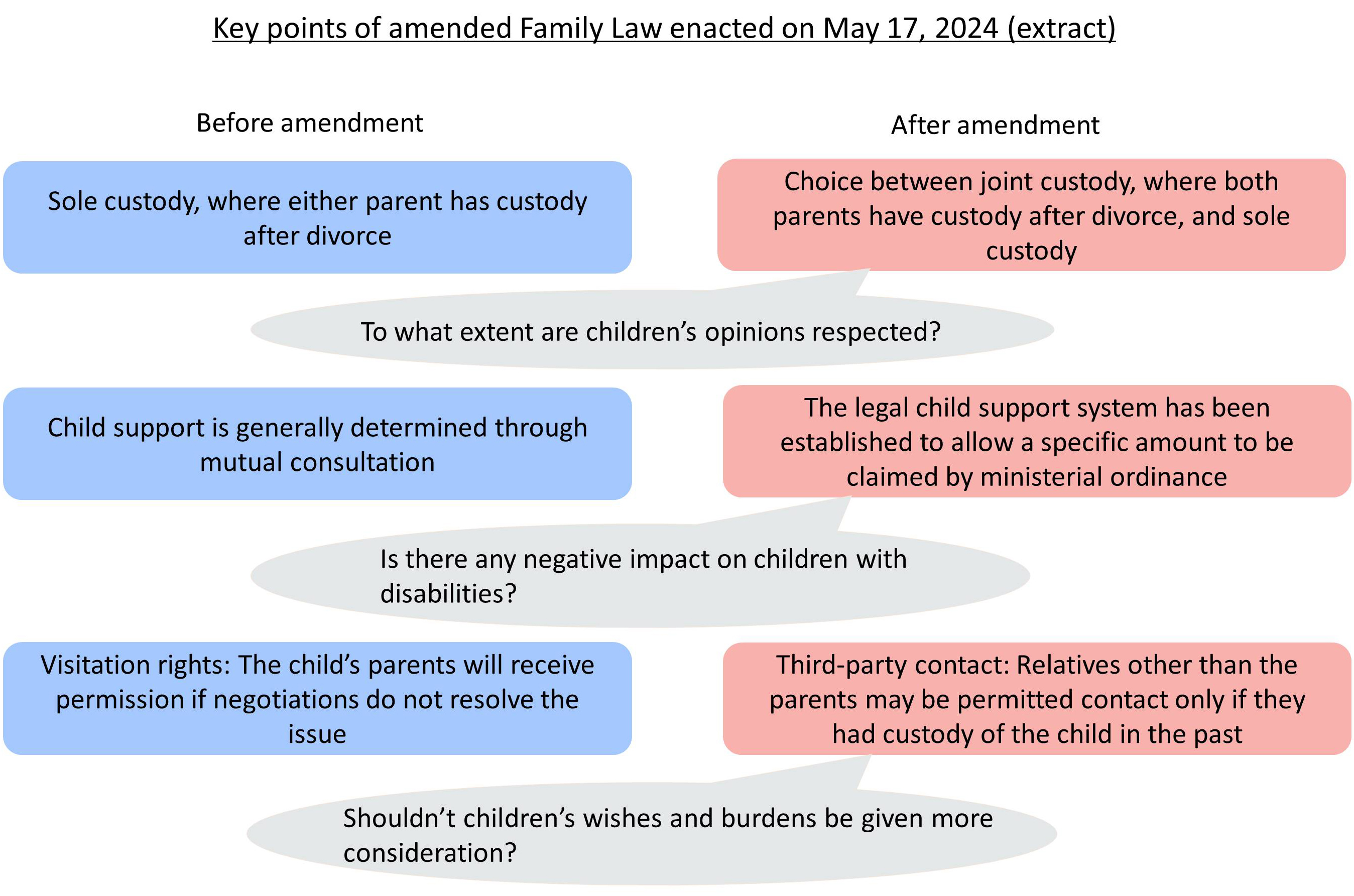

For many years in Japan, while married couples have had joint custody, either parent has had sole custody of the child after divorce. However, as the adoption of joint custody after divorce is becoming a global trend, the introduction of joint custody has been discussed in Japan as well.

That said, when observing the discussions about joint custody in Japan, it seems that the system is primarily considered as a matter of parental rights.

In other countries, joint custody has been discussed as a matter of children’s rights. While custody is literally translated as “parental rights” in Japan, other countries have approached joint custody from the perspective of children’s rights to protection or parental responsibility and obligation.

In other words, custody is discussed as parental rights in Japan, while it is discussed from the perspective of the child in other countries. This inconsistency in arguments seems to be reflected in the discussions regarding legislative improvements for joint custody in Japan.

Now, under the amended Family Law, enacted on May 17, 2024, joint custody is an option. When a couple divorces, they can choose between sole custody or joint custody by mutual agreement, and if they cannot agree, the family court will make the decision as part of the legal framework.

As a matter of course, as a premise, the principle that parents should fulfill their duties jointly for the sake of the child, even if they divorce, is justified. It must be desirable for the child if their parents cooperate through joint custody even after their divorce.

Nevertheless, I cannot help but harbor some doubts about whether this system truly serves the interests of children.

For example, this amended law includes cases involving potential child abuse and domestic violence as situations where the court cannot choose joint custody and must assign custody to one parent.

The law does include a general provision stating, “when it is found that the interests of the child will be harmed by granting custody to both parents.” In a sense, however, this may be interpreted to mean that, unless there is abuse or domestic violence, joint custody is granted in principle.

As a lawyer, I have been involved in divorce and custody disputes between couples. From my experience, cases where the decision is left to the family court in the new system are likely to include situations where the parents have not reached an agreement on custody, particularly when they do not even want to face each other.

Needless to say, the introduction of joint custody does not necessarily mean that the intense antagonism between high-conflict parents will possibly be resolved. When, under joint custody, the parents’ views differ and their discussions reach a deadlock, it is the child who bears the greatest burden.

What is needed is a system for children, not for parents’ satisfaction

In particular, matters regarding child custody and child support have often been used as bargaining chips in negotiations and visitation owing to significant conflicts of interest between divorcing couples. In light of this, I am concerned that, even if joint custody is chosen, it may ultimately be exploited for the parents’ self-satisfaction rather than for the child’s benefit.

Custody primarily gives parents the authority and responsibility to care for and educate the child in the child’s interests. One aspect of such authority is broad discretion over the child’s upbringing.

For instance, custodial parents have the authority to decide whether the child will go to a local public junior high school or a private integrated junior and high school after elementary school as part of their academic path. Parents want the authority to influence decisions during their child’s crucial life stages while the child is a minor. You can relate to such a feeling as natural in a certain way.

However, if the marital relationship becomes difficult, and divorce negotiations fail to reach an agreement, resulting in an adjudicated divorce, it is usually assumed that both parties want to distance themselves from each other (or one wants to distance the other) physically and emotionally. In such a case, how many parents would be able to have a calm face-to-face talk for the sake of the child?

Basically, when the parents cannot raise their child together, the conventional sole custody system seems to aim to give responsibility and authority for the child’s benefit by granting custody to the parent who effectively lives with and takes care of them.

Therefore, even under the joint custody system, it is essential that the parents can actually talk calmly for the sake of the child. In other words, joint custody is less necessary for divorced couples who manage to get along for the child’s benefit even if one parent has sole custody.

In any case, the amendment of the law concerning selective joint custody will be illogical if the system does not prioritize the child’s interests.

As mentioned above, decisions on the academic path are an example of custodial power. From a practical standpoint, there are surprisingly many disputes where various aspects of a child’s growth, such as entrance examinations and extracurricular activities, form conflict between parents.

When a problem arises between divorced families, the Civil Code used to adapt a stance to allow individual autonomy and refrain from court intervention. However, with the amended law, the family court will now intervene in relation to selective joint custody after divorce.

I have always maintained that joint custody should be chosen when the parents are in agreement. In the future, the court will have to determine whether to grant joint custody or sole custody when the parents do not agree, or in cases where conflict still exists. Hopefully, you will understand that this includes exceptionally difficult issues.

The parties involved should carefully consider whether joint custody is not chosen for their own sake rather than for the child’s.

Legal child support should consider children with disabilities

Moreover, the change in the regulations regarding child support in the amended law should be an important point of discussion in the future.

Traditionally, the amount of child support was determined through discussion between both parents, and one parent was supposed to pay the other, who takes care of the child. In spite of this, there were cases where parents refused to engage in discussion in the first place or refused to pay agreed-upon child support. Measures for such cases included proceedings for conciliation of domestic relations through the family court or compulsory execution.

In the amended law, the legal child support system has been established to allow individuals who divorce without an agreement on child support to claim a specific amount of child support as determined by an ordinance of the Ministry of Justice. In addition, for unpaid child support, a statutory lien has been established, which grants priority for payment over other debts. This allows the salary of the parent who has not paid child support to be seized early.

In a sense, both the legal child support system and the statutory lien are legal systems that strengthen children’s rights, and I support these systems per se. However, since I am also involved in welfare for people with disabilities, I am afraid that legal child support may not be sufficient for children with disabilities.

It will be necessary to allow for flexibility when designating the amount by a ministerial ordinance moving forward, and the system should be designed to enable the amount to be easily increased if special circumstances are recognized. On the other hand, if the legal child support system adopts the attitude, claiming, “Since the minimum amount is set by law, you should just accept it,” the negative impact of the system will be more remarkable. Although what will happen in the future remains uncertain at the moment, it is expected that child support will be broadly covered not only by the Civil Code but also by enhanced social welfare.

Third-party contact should not burden children

Furthermore, it is essential to consider whether the interests of the child are fully taken into account in the changes regarding third-party contact with them in the amended law.

Before the amendment of the law, if the parents could not reach an agreement on visitation or contact with the child after divorce and sought a decision from the court, the family court could only make a decision concerning the father or mother of the child. Meanwhile, there were also certain needs for non-custodial grandparents to see the child (their grandchild).

The amended law allows the family court to permit contact to the relatives other than the parents only if “it is found to be particularly necessary in the interests of the child,” and on the condition that “they had custody of the child in the past.”

The law has addressed the need by permitting third-party contact. In some cases, however, I believe that consideration should be given to the possibility that this could place a burden on the child.

In such cases, there is also the possibility that the contact could be sought more for rivalry between families rather than for the child’s genuine wish to have contact. As a matter of fact, I have experience as a lawyer, and I often receive inquires such as, “The grandparents on the custodial parent’s side see their grandchild almost every day. We would like to have contact because it is unfair that we cannot see them.” However, is it really a demand made for the sake of the child?

The amended law stipulates the principle that “the child’s interests must be given the highest priority in the consideration” of the sharing of expenses that custody of the child requires as well as visitation and contact. That in itself is a good thing, or rather, it is a matter of course. However, when I look at the actual legal framework, I find that the child’s perspective is not sufficiently taken into account in matters such as joint custody and third-party contact after divorce.

It seems that Japanese society needs to become more mature in understanding children’s rights, especially considering the current situation where their interests are hardly prioritized in general discussions about the amendment of the law.

* The information contained herein is current as of June 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.