National character of avoiding self-assertion and sensing the atmosphere

I have been engaged in the study of public policy focusing on economics for many years. However, I often found that applying theories and analytical methods obtained from literature in the US, a leading center of economics, to Japanese data, produced inconsistent results.

At first, I thought there might be an issue with the way the data was collected, but as I continued my research over time, I began to suspect that national character may be a related factor. Consolidating multifaceted considerations, I published a book called Nihon-jin to Nihon-shakai: Shakai Kihan kara no Apurochi (Japanese People and Society: Approaches from Japanese Social Norms) in 2022.

Partly owing to the advancement of informatization and globalization, lifestyles around the world are increasingly seen as becoming standardized. However, when considering which value standards are emphasized, I believe that differences in national character, shaped by variations in social norms between countries, undoubtedly influence a country’s systems and people’s behavior.

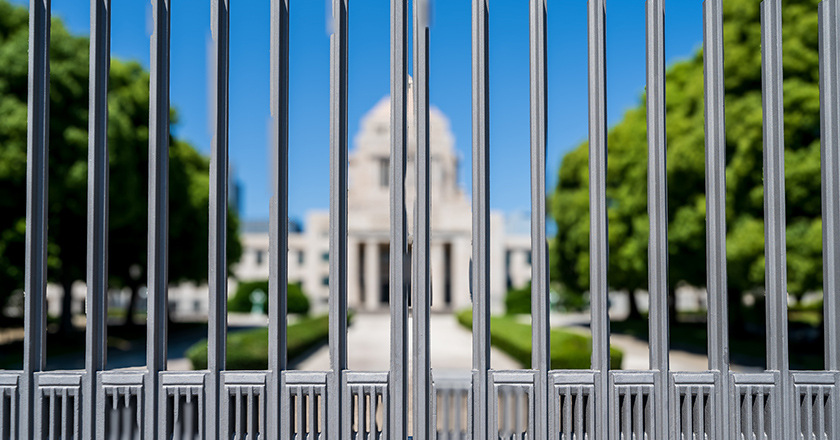

For example, Japan’s current political system is a parliamentary democracy. However, even though it is labeled a democracy, certain aspects do not function smoothly when applied to Japanese society. This is evident in recent issues such as politics and money and voters’ distrust of politics.

Certainly, democracy is a superior political system compared to authoritarian regimes and dictatorships. However, there are some requirements for it to function. With this in mind, I would like to return to the fundamental question of what Japan’s democracy lacks.

First of all, for democracy to function, each individual must form their own opinions, express them, and participate equally in politics. People with differing opinions engage in vigorous discussions, aiming to consolidate their views and decide on policies.

However, this basic premise does not apply in Japan. This is because the Japanese tend to avoid self-assertion in order to be accepted by others. Consequently, they may be brought up to sense the environment, as self-assertion can often lead to confrontation and friction with those with differing opinions.

In Japan, where people tend to avoid asserting themselves, maintaining good relationships with others is seen as more important than engaging in discussions to share useful opinions and shape policies. In other words, Japanese people are not used to thinking for themselves or engaging in discussion with others. If people cannot assert themselves in the first place, they will fail at the very beginning, even if they try to establish better policies through discussion or find a compromise solution.

All-encompassing policies impose a heavy burden on voters

On the other hand, it is often said that Japan’s distinctive four seasons and frequent experiences with natural disasters have helped develop the Japanese people’s sense. Additionally, Japan is an island nation, geographically isolated from its neighbors. Within the country, people often live in small, densely populated residential areas. This environment heightens sensitivity to human relationships, and it is often said that their behavioral standards are based on how they are perceived by others.

In other words, Japanese people prioritize relationships within their local community, while cultivating relationships based on mutual respect and non-interference with those outside their area, avoiding any form of inconvenience. In other words, they find security, stability, and safety in being part of a small, homogeneous world.

While this high degree of homogeneity benefits group activities, it has a drawback: a tendency for exclusivity toward those who are different or new to the group. If differing opinions are excluded, the diversity of opinions essential for an ideal democracy cannot be guaranteed.

Even when differing opinions are not explicitly excluded, Japanese people avoid disrupting harmony in human relationships and tend to conform to majority opinions, influenced by how they are perceived by others. This tendency is also an aspect of the Japanese national character, and it results in the drawback that discussions do not progress to a deeper level.

In a democratic system, if a unanimous decision cannot be reached, a majority vote is conducted. A functioning democracy leads to vigorous policy discussions. As a result, when various opinions are merged into one that is supported by the majority, policies that significantly change society may be adopted even if they disadvantage some individuals.

However, Japanese politicians have also adopted the Japanese national character, treating their constituents with excessive caution and striving to avoid confrontation or friction. They typically steer clear of unwelcome matters such as tax burdens, and focus instead on favorable topics like benefits. Many political pledges end up superficial and overly inclusive, vaguely promising benefits for the entire nation.

Not only the ruling parties but also the opposition parties cater to all sides, and in a broad framework, their policies actually show no significant differences. Even the Japanese Communist Party, which aims for socialistic reform in the long term in the party program, advocates politically neutral and welfare-state policies during election campaigns.

In other countries, some political parties advocate policies focused on a single area, such as growth, distribution, or the environment, while others prioritize the interests of specific segments of the population. However, since Japanese politics reflects the national character that considers the needs of the entire population, and politicians are expected to act in accordance with their roles, all political parties tend to propose similar, all-encompassing policies.

In addition, it is difficult to fully comprehend overly inclusive policies. Predicting their feasibility and the overall consequences, even if they are implemented, is also challenging.

Evaluating such broad and unfocused policies imposes a huge burden on constituents. In such cases, voters may choose not to vote, or make decisions based on non-policy issues such as scandals.

Why aren’t there massive protests despite political dissatisfaction?

Politics that appeases the public prioritizes providing benefits to the entire nation over imposing burdens. As a result, the government’s fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP has reached exceptionally high levels compared to other advanced countries, raising concerns that substantial debts will be passed onto future generations.

According to the World Economic Outlook released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April 2024, the general government gross debt-to-GDP ratio in major Western advanced countries ranges from approximately 100% to 120%, while in Japan, it has reached 250%, more than twice as high.

Even when it is necessary to bear burdens or make changes, it can involve considerable pain. Despite recognizing its necessity, the Japanese show resistance when burdens and changes are imposed at the national level, placing a high value on security, stability, and safety. Taking this attitude into account, politicians do not make campaign pledges about policies that will entail great burdens and changes, nor do they implement them.

On the other hand, Japanese politics struggles with issues at a more fundamental level than policy matters, and it appears that policy discussions, which are crucial in a democracy, are stagnating. For example, resolving the so-called slush fund scandals has taken a great deal of time. These scandals involve portions of revenue from political fund raising parties that were not reported in the political income and expenditure reports, and are allegedly used as secret funds. Public opinion polls conducted by the media indicate that the public remains largely dissatisfied with the solutions proposed by the government.

However, the dissatisfaction among the majority has not led to widespread large-scale protests that threaten the regime, nor to the emergence of a new political force to completely change the situation. Underlying this situation, too, is the Japanese national character, which reflects a balance between “honne” (true feelings) and “tatemae” (public stance).

As Chie Nakane and Ruth Benedict have pointed out, Japan has a distinctive “vertically structured or hierarchical society”: Higher-ranking individuals are expected to care for those below them, who, in turn, show respect to their superiors. The Japanese generally expect that those in higher positions in society to fulfill roles appropriate for their status. They also trust that such individuals will meet these expectations, though there may be some variations among individuals.

Since this belief also applies to politicians, many Japanese do not expect them to commit any serious wrongdoing, which might explain the lack of strong public opposition to politicians.

How to improve Japan’s democracy

Which direction will Japanese politics take moving forward, given that democracy does not align well with the Japanese national character?

If the government continues to implement policies that delay imposing burdens and changes to accommodate the entire population, the government’s fiscal deficit and debt will increase. As a result, it may eventually become difficult to raise funds through the issuance of government bonds.

One solution is to utilize external pressure. Historically, when Japan underwent major changes, such as the Meiji Restoration and Japan’s defeat in the war, external factors were involved. It is likely that external forces will also influence modern Japanese politics. To be specific, Japan would need to accept economic and fiscal consolidation policies that entail pain and changes as a condition for receiving an IMF loan.

However, this measure is a response to the consequences resulting from a malfunctioning democracy in Japan, not a solution to the root problem.

Then, what steps should be taken to improve the functioning of democracy in Japan? As I have repeatedly explained, the Japanese national character lies at the root of this issue, making it difficult to achieve immediate improvements. The Japanese tendency to prioritize consideration for others and avoid self-assertion is incompatible with democracy. Furthermore, other aspects of Japanese national characteristics, such as the lack of universal standards of value and an exclusive focus on maintaining human relationships within local communities, are not suitable for policy discussions.

Even so, there is almost no alternative but to make policy decisions through democracy.

One potential solution is to ensure that the fundamentals of democracy are firmly established through the education system. In Japan, discussions about politics and political parties tend to be avoided, as they can encroach on people’s value judgments and lead to confrontation and friction. These topics are rarely tackled head-on in school education as well. In this context, policies should be separated from politics and political parties, and the habit of discussing solely the meaning and effects of policies should be fostered in school education.

In the process of education, students should learn to recognize that differing opinions stem purely from various perspectives on policy effects and should be considered separately from the person expressing them, in other words, from human relationships. In the absence of such education and habits, increasing voter turnout alone will not ensure that good policies are selected.

In the context of politics, which reflects the Japanese national character and promotes overly broad policies, it would be easier for voters to make evaluations if the differences between the parties (candidates) were made clearer during elections. Analysis by experts is essential for knowing the effects of policies. More research should be conducted in this field, and a wide range of policy analysis should be made available to voters to help them evaluate policy effects.

Implementing these measures would be challenging owing to the Japanese national character. However, I believe that considering the issues and consequences of Japan’s democracy, as discussed here, is a significant first step toward its improvement.

* The information contained herein is current as of July 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.