The Historical Background of the Fukushima Daiichi Plant

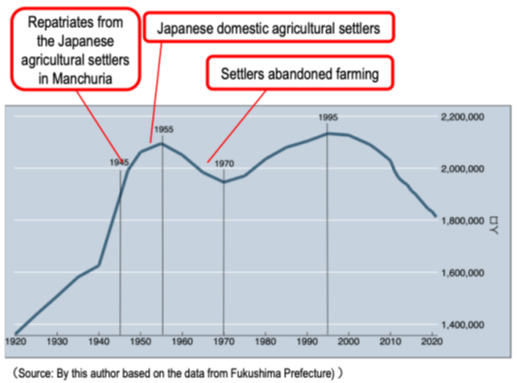

In the 1960s, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was developed in the area to revitalize the local economy. After World War II, many settlers, including repatriates in the form of Japanese agricultural settlers in Manchuria under Japan’s colonial policy and postwar Japanese domestic agricultural settlers(kokunai-kaitaku-min) from other prefectures, moved to Fukushima Prefecture.

Historically, after the war ended in 1945, the population of Fukushima Prefecture initially rose owing to the influx of repatriates and newcomers. (See Figure 1 below.) However, after peaking in 1955, the population declined as many Japanese domestic agricultural settlers(kokunai-kaitaku-min) abandoned farming. This was mainly because the areas they settled in were often unsuitable for agricultural activities, causing many farmers to leave and contributing to a stagnant local economy. In response to these challenges, the construction of nuclear power plants was promoted as a strategy to revitalize the local economy.

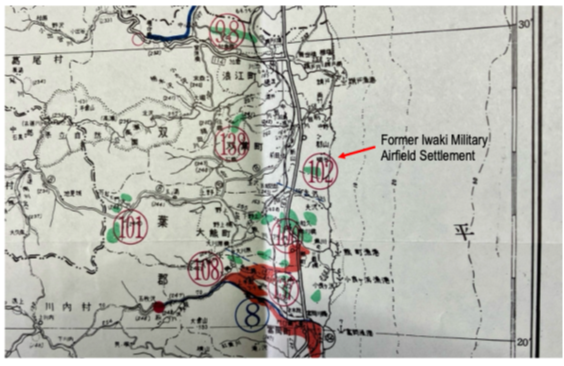

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is located on the former Iwaki Military Airfield. (See Figure 2 below.) Out of the total area of approximately 4,170 acres (1.26 million tsubo), about 990 acres (300,000 tsubo) were the site of a former military airfield, which had been transferred to a private company for development. The remaining and larger portion—around 3,180 acres (960,000 tsubo)—was land that had been settled on by postwar Japanese domestic agricultural settlers (kokunai-kaitaku-min) under Japan’s internal settlement policy

(Source: Fukushima Prefecture Agricultural Land Division (1970) “Historical Records of Agricultural Land Development in Fukushima Prefecture, Vol. 2, Supplementary Figures)

The residents’ backgrounds varied significantly between traditional farmers and postwar Japanese domestic agricultural settlers (kokunai-kaitaku-min) in this area. The land occupied by the pioneers struggled with economic instability due to low productivity and a growing trend of farming abandonment. These pioneers also tended to be less settled, resulting in weaker local communities and a lower likelihood of large-scale opposition.

In fact, a report from the Japan Atomic Energy Industries Council (1970) noted that there were almost no opposition movements in these settlement areas. In contrast, the adjacent areas, populated by many traditional farmers, strongly opposed nuclear power plants.

Therefore, each region’s differing economic situation and community dynamics led to varying reactions regarding the construction of the nuclear power plant. The postwar Japanese domestic agricultural settlers (kokunai-kaitaku-min) were deemed less likely to oppose the plants and the land inhabited by them more suitable for the establishment of a nuclear power plant.

Since the 2011 accident, there has been extensive debate about the social and economic impacts of nuclear power plants; however, empirical studies on this topic are limited, and opinions often conflict. In my research, I focused on the impact of nuclear power on local employment using newly constructed long-term data.

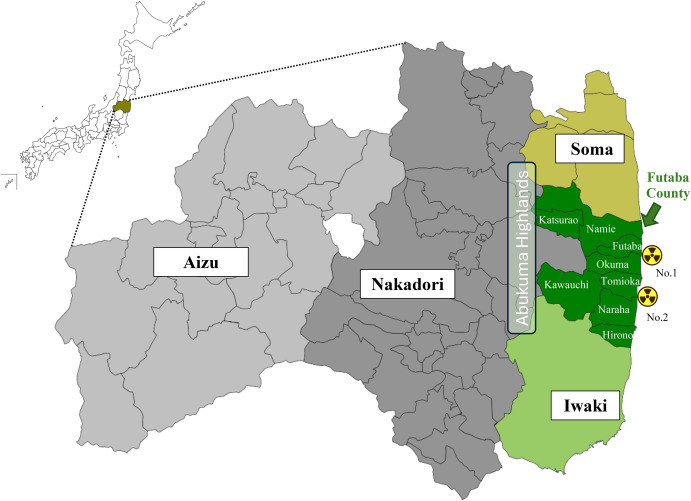

Why the Fukushima Nuclear Plant “Increased” Agricultural Employment

Fukushima Prefecture is divided into three areas: Hamadori, Nakadori, and Aizu. (See Figure 3 below.) Hamadori is particularly noteworthy because it houses both the Fukushima Daiichi (Nuclear Power Plant No.1) and Daini (Nuclear Power Plant No.2) nuclear power plants. This area has limited geographical and physical connections to the other regions. The Abukuma Highlands, which run through the prefecture, make it more difficult for people and goods to move around than the actual distances suggest, impacting the economic structure between these areas.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114801)

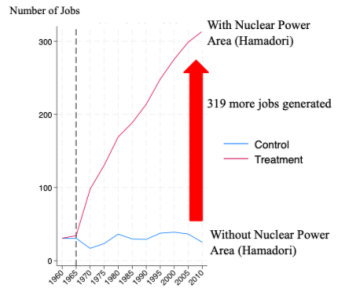

In this research, long-term data from 1960 to 2010 was analyzed to compare employment differences between areas with (Hamadori) and without (Aizu and Nakadori) nuclear power plants. I found that employment in the electricity, gas, and water sectors increased by 319 jobs in Hamadori, surrounding the nuclear power plants. (See Figure 4.) This increase represents one of the economic effects of the nuclear power plants, as similar growth in employment is not observed in regions without nuclear facilities, such as Nakadori and Aizu.

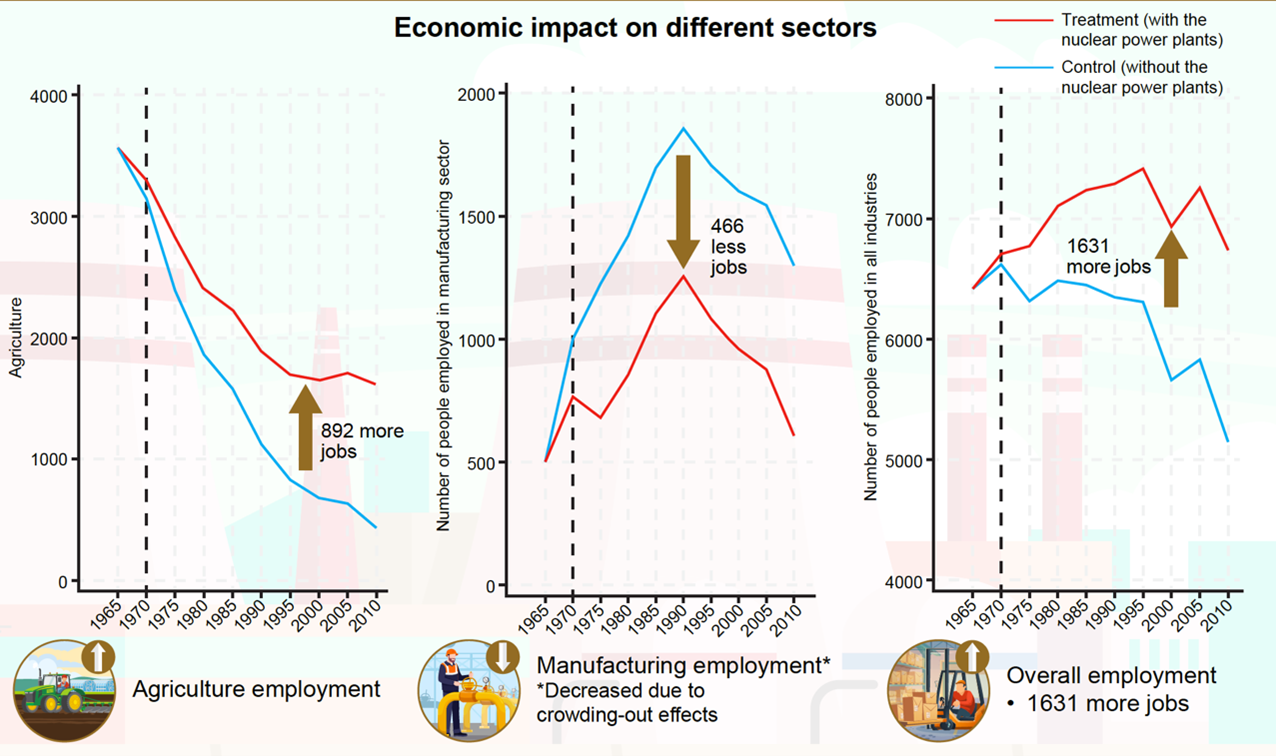

The impact on agriculture was unexpected. (See Figure 5.) Previous studies suggested that constructing nuclear power plants led to a decline in the agricultural sector. However, this analysis indicates that agricultural employment decreased slower in areas near nuclear power plants compared to other regions. This is likely due to the higher wages associated with the nuclear power plants.

(Based on municipal level data from 1960-2010)

**Wages at the Nuclear Power Plant and Their Impact on Local Industries**

Wages at the nuclear power plant were based on Tokyo standards, making them significantly higher than those in other industries in the region. In Hamadori, it is common for three generations to live together, and having a family member employed at the nuclear power plant helped stabilize family finances. This financial stability enabled families to continue their traditional farming businesses.

Analysis of long-term data shows that 892 more agricultural jobs were maintained in areas with nuclear power plants compared to other regions. This indicates that the income earned by nuclear workers may have indirectly supported the survival of agriculture.

Conversely, the local manufacturing industry suffered a major setback. Few local companies could compete with the high wages offered by the nuclear power plants, leading to the loss of 466 jobs. Two main factors contributed to this negative impact on the manufacturing sector: first, many workers left local manufacturing jobs to pursue higher-paying positions at the nuclear power plants; second, local manufacturers felt pressured to raise wages to match those at the nuclear facilities in order to retain their workforce, which strained their operations. In essence, large corporations like TEPCO drained the local labor force, diminishing the competitiveness of local manufacturers.

Looking at all sectors, including services, employment increased by 1,631 jobs. This boost is partly a result of the significant influx of funds linked to the nuclear power plant. However, it is important to note that the overall industrial structure in the areas surrounding the Fukushima nuclear power plant has not changed as much as expected.

Typically, economic development is characterized by a shift from primary industries (agriculture) to secondary industries (manufacturing) and then to tertiary industries (services). In the Fukushima area, while agriculture declined relatively slowly, the growth of the manufacturing sector stagnated, hindering the normal progression of industrial development. In other words, the presence of nuclear power plants distorted the industrial balance in the region.

Transitioning from Nuclear Dependency and Decommissioning Industries: Towards Sustainable Recovery in Fukushima

Currently, revitalizing agriculture in the areas surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is extremely challenging. Through interviews conducted in the Hamadori area after the disaster, it became evident that local residents have a strong attachment to agriculture. Despite this attachment, the revival of farming remains difficult.

Moreover, the government’s reconstruction policy primarily focuses on the manufacturing sector. However, research indicates that the high wages in the nuclear power and decommissioning industries hinder the development of local manufacturing. Therefore, promoting this sector will not be as straightforward as hoped.

Fourteen years have passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake, yet many residents are still unable to return to their hometowns and continue to feel a profound sense of loss. Regaining the agricultural lifestyle they cherished before the disaster is proving difficult, and the reconstruction direction is shifting toward new industries, such as robotics and decommissioning work. However, these changes may diverge significantly from the reconstruction of the pre-disaster lifestyle that residents desire.

Policies that reflect the voices of disaster victims and evacuees are essential to bridge this gap. Reconstruction efforts must go beyond mere economic revitalization and resonate with the community’s memories and aspirations. This would be the first step toward achieving a genuinely sustainable reconstruction of Hamadori that does not rely on nuclear power plants or decommissioned industries.

The analysis, in this Opinion, summarizes the content of the following article. The full text is available at the link below.

Shimada, Go. 2024. “Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant impact on regional economies from 1960 to 2010.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 203:114801.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114801

* The information contained herein is current as of December 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.