Can teachers’ long-hours of overwork be corrected by work-style reforms?

I am mainly conducting research on policies and systems related to teacher training, hiring, and continuing professional development, especially by comparing Japan with England.

England, except for a certain period in the 1970s, has consistently suffered from a teacher shortage since the war. In comparison, in Japan, it can be said that the teacher shortage did not become evident until recently. However, teachers on site have for a long time complained about the issue of overwork.

In the first place, in order to resolve the shortage of teachers, we need to correct the overwork of teachers, and let people think “I want to become a teacher.” The quota of public school teachers is decided depending on the number of classes, based on act and ordinance. However, it is not linked to an increase or decrease in the workload of teachers.

You may know that the number of pages of textbooks that are used by children increased by the datsu-yutori (breakaway from pressure-free) education policy. In fact, the course of study has changed and the content, type, and hours of lessons have increased. However, this was not reflected in the quota of teachers. Therefore, the increased portion of the content and hours of teaching had to be dealt with by increasing the burden per person (number of class hours).

Moreover, while the annual class hours of each subject are prescribed by the course of study, there is no rule concerning how many hours each teacher has to take on. Some researchers are proposing that in order to resolve the issue of overwork, the class hours per teacher (mochi-koma-su) should be capped, and the number of teachers should be increased according to the mochi-koma-su.

Personally, I think we are already at the stage where it is difficult to correct the long-hours just by implementing the work-style reforms. Furthermore, I think we should not overlook what the various urgent measures that are introduced to resolve the teacher shortage issue will lead to in the long term.

For a long time, our country was suppressive against the number of teaching certificate holders

Against the issue of the teacher shortage, MEXT finally seriously started to understand the real situation in the latter half of 2010s. However, when we look at the national policy on the training of teachers in the long run, in fact, it has been moving in the direction of suppressing the number of teacher certificate holders for a long time.

What should not be overlooked as a premise to discussing the current teacher shortage is that since the mid-1980s, as a part of fiscal restructuring, the reduction in the quota for the state-run universities and faculties to train teachers was advanced. Enrollment quota of 20,100 in FY1986 was reduced to 9,770 in FY2000. Moreover, starting from 2009, the system to renew the teacher certificate was implemented, and the term of 10 years was established for the teacher certificate. This also caused a reduction in the number of teacher certificate holders. This certificate renewal system was abolished in July 2022, when the teacher shortage became visible.

If we look back at the history, in the system to train teachers in post-war Japan, teacher training at the university has been regarded as one of the two major principles. However, especially in the teacher certificate system reform since the 1980s, measures to hollow out this principle of teacher training at university were repeatedly implemented.

At universities, curricula for the teacher-training course are prepared according to the Educational Personnel Certificate Act, and students will gain credits and be awarded a certificate. If we focus on the required number of credits to obtain the certificate and look at it from the post-war period to the current times, we can draw a line in the 1988 and the 1998 revision of Act, as shown in the figure.

Especially the 1988 revision is major. Until then, the teaching certificate was divided into categories called ko (A) and otsu (B). For example, broad areas such as social studies and sciences are A, while Japanese language, mathematics, foreign language, etc. are B.

In the 1988 revision, the division of A and B was removed, and the wording changed from “1-kyu (class 1)” to “1-shu (type 1).” Along with the increase in required number of credits to 59, formerly A courses such as social sciences increased by 5 credits as for “professional study” and formerly B courses such as Japanese language increased by 5 credits as for “professional study” and by 8 credits as for “teaching subjects.” In other words, it increased by as much as 13 credits at a maximum.

Moreover, in the 1998 revision, 8 credits were newly established as a classification called “teaching subject or professional study” in order to distinguish each university. Furthermore, the number of required credits related to “teaching subjects” was reduced by 20 credits, and the number of credits related to “professional study” was increased by 12. At the end of 1980s, when difficulties related to children started to emerge, in order to cultivate teachers that could respond to them, “professional study” subjects were added. It looks like the burden did not change as the whole framework of 59 credits did not change. However, for students in the general universities (universities and faculties like ours, where the acquisition of a teaching certificate is not required for graduation), while credits related to “teaching subject” can be obtained if they take subjects of faculties, “professional subjects” needs to be registered in addition to the credits required for graduation. As a result, substantially, the requirement to obtain a teaching certificate became more demanding.

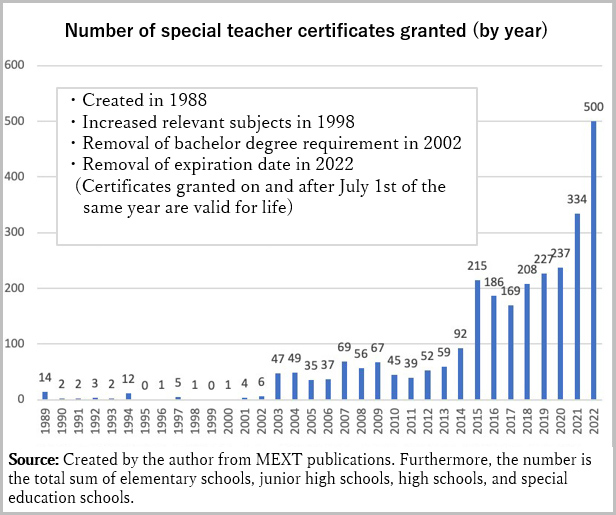

Thus, while the 1988 Educational Personnel Certificate Act raised the requirements for training in universities, it created at the same time a system called the special teacher certificate that enables the acquisition of the certificate without going through the training process. The special teacher certificate is a certificate to be granted after the prefectural school board conducted the teacher examination for people with working experience having “specialized knowledge or skill related to the subject (which they will be teaching).”

Initially, when the special teacher certificate system started, the special certificates were valid for not more than 10 years within the prefecture, and the subjects which one can teach with a special certificate were limited. However, afterwards, more and more conditions were relaxed after repeated act revisions. I was especially surprised that the condition of obtaining a bachelor degree, that is to say, graduating from a university, was removed, by the 2002 revision of the Educational Personnel Certificate Act.

Deregulations that opened a path to becoming a teacher without going through the teacher training at university and graduating have been implemented, while making it more demanding to obtain a teacher certificate at university.

Concerns about the special teacher certificate system that enables people to become a teacher without going through teacher training

The number of granted special teacher certificates had not been increased until recent years despite the relaxation of conditions. However, it started to increase amid the recent teacher shortage, and MEXT is encouraging the system more and more as some sort of a last resort, and it is expected to increase rapidly.

However, for me, this trend feels like trying to collapse the premise that was thought of as common sense that a school teacher is someone who obtained a teacher certificate after being trained at university.

Especially for someone like me who is interested in the teacher training at university, as well as the teacher shortage issue itself, I am concerned about what kind of impact the introduced (without other choice) measures to skip the training at universities to resolve the issue have on the quality of the occupational group called teaching profession in the long term.

One of them is related to the actual handling of children and students. Of course, it does not mean that it is sufficient if one studied pedagogy and psychology. However, I do not think that the downside of not going through the teacher training program at university, where one builds up a certain level of academic insights, is minor. MEXT itself says that “the ones who are hired by […] the special teacher certificate are expected not to be familiar with the knowledge and skill that is related to the teaching profession in general.” (“Points of concern related to the teacher’s certificate, etc., to respond to the issue of the teacher shortage (Request)” Educational Human Resources Policy Division, Education Policy Bureau, MEXT, April 20, 2022)

In fact, I heard about a case of a person who had a career which required a language skill at a company obtaining a special teacher certificate for English and becoming a teacher. However, the person could not build a good student-teacher relationship with minors who were very much younger and ended up having difficulties, including in the English classes.

I would like to add that this does not mean that people with a special teacher certificate are not qualified to become a teacher. However, at least, the current special teacher certificate system has a structure to enable people to become a teacher as long as they are acknowledged as a specialist of a subject. In contrast to the case of obtaining a certificate at university, it is called specialist when there are no need to learn basic content of subjects with the courses, including “general comprehensive content,” which broadly encompass the scholarly area of the courses. Is it sufficient to be merely a specialist of a specific area of a subject, and isn’t it problematic not to learn pedagogy and psychology? This is a discussion that I would like to raise.

For example, if we think about the instruction of physical education, even if one had an excellent capacity and achievements as an athlete, does one have the ability to instruct various games as a PE teacher to various children, is safety considered during the instruction, including the children’s future? For example, do they know whether they can let children do something during their development stage? I think these are the things that cannot be naturally done if one did not constantly study after broadly obtaining basic knowledge of physical education studies and pedagogy of physical education.

Of course, again, I am not saying here that it is sufficient if one is trained at university. On the contrary, I am calling for the re-examination of the status of teacher training at university.

University’s involvement with teacher training is significant for both society and universities

Because strong appeals have been made against the shortage of teachers, we are all the more required to go back to basics and have careful discussion about teacher training at university. I think we can discuss this mainly from two aspects.

Firstly, to update the argument related to the importance of conducting the teacher training at university, which started from the critical awareness against the pre-Second World War normal school training.

Criticism against normal school training is, in other words, a trust and expectation for universities as a place of research that is treated as a subject of constant exploration and updating, rather than the content being taught there being regulated by a framework that is determined by someone somewhere. Moreover, in Japan, where the admitted students are overwhelmingly dominated by 18 year olds, we cannot dismiss the meaning of university as a place of adolescent education.

The slogan of the current course of study is “independent-minded, dialogical, and deep learning.” However, if the teacher did not have experience of an independent-minded and dialogical learning, one cannot offer education to allow students to experience it.

It has been basics of university education to study by analyzing the current status by oneself and clarifying the challenges, establish the theme, and set the response measures and strategies on one’s own. I think it is the responsibility of university education as a whole to cultivate such capability, and also the biggest advantage of the teacher training at the university.

Secondly, although it is not so often discussed compared to the first point, it is a discussion to reconsider the significance and benefit for a university to be involved in the teacher training.

For the continuous development of an academic discipline, it is naturally necessary to continue to stably secure the successor who will take up the field, and such discipline to be widely recognized by the public. For that, through the education at the elementary, junior high, and high schools, children’s interest in the field of study, or a little more broadly, the admiration for the research itself, need to be inspired.

Development of research is supported not only by the work of a prominent scholar but also by teachers who are in charge of education at elementary, junior high, and high schools. For a university to train teachers who understand the fun and depth of learning, through that (teacher training), university itself can receive long-term benefits.

Teacher shortages are a common long-standing issue internationally, and it was rather late becoming visible in Japan. Moreover, it is also seen as a common measure to promote skipping and deviating from the training of teachers at university as a response to the issue.

However, I think it is short-sighted and even a bad move to only implement promoting measures to respond to the teacher shortage. In a very short term, it may look like it helps resolve the shortage issue, but in the long term, the quality of education could be undermined, and schoolteachers could be removed from their aspired profession by children.

It could look like a detour, but faced with the teacher shortage, I think we have no choice other than to make the school workplace a place where teachers can realize the inherent attractiveness and responsiveness of their work, so that the teaching profession will be chosen by people. In order to do that, I think that the role of educational administration is the most important, but how universities respond to the new situation, for example, conducting teaching employment examination earlier during the third year of an undergraduate program, is at stake.

* The information contained herein is current as of July 2024.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.