Support for Reconstruction from the Great Hanshin-Awaji and Great East Japan Earthquakes

The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (1995) and the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011) are two of the most prominent earthquakes in Japan’s postwar history. The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of Magnitude 7.3, the first officially recorded quake with a seismic intensity of seven on the Japanese scale, was an urban disaster whose effects included the collapse of urban infrastructure such as expressways, railways, Shinkansen-railway, subway and life-lines facilities, including office buildings, homes due to its strong seismic vibrations as well as fires in areas that had high concentrations of wooden structures. One hundred eleven thousand building units were collapsed and five thousand and five hundred people killed. The Great East Japan Earthquake of magnitude 9.0 caused enormous structural damage and loss of life especially due to its massive tsunami. One hundred thirteen thousand building units were lost and nineteen thousand people killed and missing.

At the time the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck, I was putting the finishing touches on a study estimating the damage of an earthquake with an epicenter beneath central Tokyo, as a member of a Tokyo Metropolitan Government committee. After visiting the areas affected by the earthquake, I proposed that one lesson we should learn from the disaster was “the necessity of preparing restoration measures in advance in order to recover swiftly from the damage of an earthquake with an epicenter beneath central Tokyo, which is projected to cause at least five times the damage of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, in which reconstruction efforts began immediately following the quake.” This was the start of Tokyo’s pre-disaster restoration efforts, and also of my study on pre-disaster restoration. How is it done? I have developed methodology of Pre-Disaster Restoration and Recovery-Based Community Development Drills.

By a curious coincidence, when the Great East Japan Earthquake struck. I witnessed the disastrous scene in the affected areas as part of studies conducted for academic societies and other activities, and I began academic activities in support of reconstruction in the affected areas.

The Union of Kansai Governments, an association of local governments covering a broad region in western Japan, acted to provide aid to local governments affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, with Hyogo Prefecture aiding Miyagi Prefecture. Since I also serve as a senior researcher with Hyogo Prefecture’s Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution, I ended up working to aid recovery as a deputy chairperson of the disaster recovery planning committee in the town of Minami-sanriku. In surveying the affected areas, I also noticed that Meiji University alumni were active across the region. After coming to Meiji University in April 2011, I proposed reconstruction aid efforts to be conducted by the university. After that, we concluded agreements on support for restoration with the cities of Ofunato in Iwate Prefecture and Kesen-numa in Miyagi Prefecture and the town of Shinchi in Fukushima Prefecture and established the Meiji University Tohoku Regeneration Support Platform, and even today the University continues a diverse range of aid activities in the region.

Consensus on Disaster Recovery Refers to a Vision of the Future of Reconstruction that is Shared among Residents

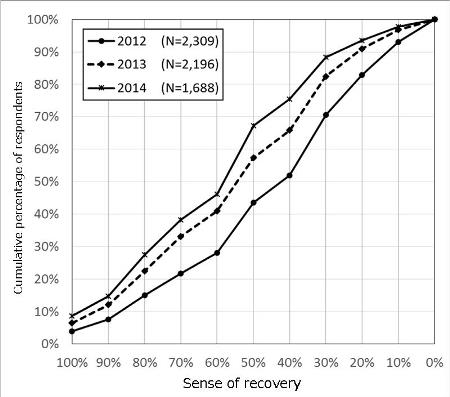

Since 2012 I have continued annual surveys of the reconstruction efforts of disaster victims in Ofunato, Kesen-numa, and Shinchi, as one academic activity related to the Great East Japan Earthquake. This is intended to propose aid and public policy to help as many residents as possible to return to stable ways of life soon, by elucidating the changes over the years in the state of restoration, as expressed in disaster victims’ sense that their way of life has recovered, and the primary causes of these changes. These surveys have shown that disaster victims’ sense that their way of life has recovered improves when their diets have returned to their previous levels, their work and income have recovered, and they see prospects for rebuilding their homes. While self-support in the form of preparing their own meals instead of being provided with meals by others and rebuilding of employment are very important, there are differences apparent among individual victims in the recovery of disaster victims’ ways of life and among regions in the reconstruction of affected areas.

One notable example concerns the relationship between prospects for rebuilding of homes and the progress of relocation of coastal communities to higher elevations. In Shinchi, progress is being made on town-wide recovery efforts, as for example an agreement had been reached by the third year after the disaster to relocate the entire community to higher elevation and during 2014 about 70% of disaster victims would rebuild their homes at higher elevations. This progress has been realized because traditionally the community has had strong ties, and all of them who lost homes are continuing to live temporally in Shinchi after disaster, it was made possible by identifying and discussing residents’ individual needs in gatherings held by each settlement in the community. While Meiji University also assisted in these workshops as supported stuffs, what was most important was the approach of reaching a conclusion only after all participants had stated what they wanted to say. While it might appear to be a troublesome process that would be unable to reach a conclusion, in fact these decisions were essential step in recovery, as the fastest route toward consensus building. This consensus represented a shared vision of the future for the town, describing the type of town that would be reconstructed. It was not the kind of consensus that can be formed through application of legal authority and legal systems. In many cases, those affected areas where relocation to higher elevation is being delayed are the ones where there has not been sufficient discussion among residents.

Passing four years since the Great East Japan Earthquake, recovery and restoration advanced slowly but steadily. But there are many people who could not have a sense of restoration from a disaster. The gap between the affected people’s recovery and the affected communities is increasing. It is important to restore an employment in affected community which is recovery of incomes of affected people. Recovery of incomes can lead restoration of individual’s usual life and rebuilding of homes. It is not enough to reconstruct a public works and houses but to recover jobs foe people.

Thinking About how to Recover By Envisioning the Damage that a Disaster Would Cause

I have studied disaster prevention and disaster recovery based on grounding in city planning studies. I was inspired by a destructive fire in 1971 in the city of Sakata, Yamagata Prefecture. The fire broke out at dusk in late October under a strong wind and by the following morning it had burned 25 hectares in the center of the city. I visited the site 24 hours after the fire was extinguished, as it still was enshrouded in stifling heat and strange odors. It was quite a shock. I thought, “It is unacceptable that a city so beautiful and comfortable could disappear like this in a single night.” Based on this belief, I chose as the topics of my research the questions of what kinds of cities would be more resilient against disaster and how cities should be reconstructed after a disaster. Since my research concerns disaster-resilient urban and community development and how to reconstruct disaster-affected areas, today I am studying the cities and areas affected by disaster.

In part because I spent a long time at Tokyo Metropolitan University, through now I have used Tokyo as a model city in studying earthquake countermeasures including disaster prevention and recovery. Since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake I also have studied pre-disaster restoration treating Tokyo as a field of study, looking at how Tokyo could recover from an earthquake which would cause directly beneath its central districts. This research topic builds on the concepts of preparing for recovery by thinking in advance about recovery measures based on anticipated damage and of implementing pre-disaster restoration by doing what can be done now to minimize damage and enable a speedy recovery after a future disaster, thus giving practical form to a vision of a future city capable of recovering from a disaster and of building back better than before a disaster. It also involves promoting efforts to minimize damage, and inevitably it should lead to both disaster prevention and mitigation. For example, instead of relocating to higher elevation after a massive tsunami that has destroyed 80% of coastal area in the Great East Japan Earthquake, relocation to higher elevation would be conducted in advance. Movement in this direction has begun today. Relocation to higher elevation in advance is included in the proposed act on special measures intended to mitigate the damage of a massive Nankai Trough earthquake, the likelihood of which is increasing. While the national government covers the entire cost of recovery from a disaster, part of the cost of pre-disaster relocation to higher elevation in advance would be covered by local government. In fact, in one community in Shikoku island region, the movement toward relocation to higher elevation in advance has been stalled because of an inability to raise the funds needed to cover these costs. The amount of funds needed is only 100 million yen.

Tokyo’s Recovery-Based Community Development Drills, an Initiative Toward Pre-Disaster Restoration

Recently the Tokyo Metropolitan Government has been advancing two kinds of drills. One is a drill, sensing the need to conduct drills, to enable government employees to become proficient in the steps needed to move forward with recovery, and the other is a recovery-based community development drills together with local residents and local governments, for development reflecting recovery considerations for areas with high concentrations of wooden structures, which are highly vulnerable and have the strongest need for community development for disaster prevention purposes. In these drills, in which I play a part as a core team member, participants think together about what kind of community development should be carried out to recover from a disaster if one were to occur today. Through now, the region has advanced community development based on disaster prevention. However, if for example the subject comes up of making the community more resilient to disaster through expanding its streets, even though many residents may indicate their understanding of the necessity of doing so they are reluctant to agree to street expansion that would involve steps such as relocation of residents. In recovery-based community development drills, participants view images of simulation of the damage caused by an earthquake or fire and then discuss how to reconstruct the community from the post-disaster ruins. They realize that they must take some steps on their own, and this helps to generate wisdom. For example, they may propose that replacing walls of concrete blocks with hedges would enable fire trucks to pass even through narrow passages in an emergency, by driving over the hedges, but that broadening the street would be even safer. Pre-disaster restoration refers to thinking about the kind of town that residents want their children, grandchildren, and posterity to live in, and putting such ideas into practice as part of community development for disaster-prevention purposes.

It is not so easy to expand the street as a disaster prevention. However, the lack of a land-register survey is a subject of concern with regard to not only community development for recovery but also that for disaster prevention in connection with a predicted future earthquake feared to strike directly beneath Tokyo. In many cases the data in land registers is inaccurate, as no accurate surveys have been conducted of information such as property lines, lot sizes, and ownership in areas such as those with high concentrations of wooden structures. It is impossible to advance either disaster prevention or rebuilding of individual homes and community-wide reconstruction while the boundaries between lots of land are uncertain. Local governments need to conduct land-register surveys soon as one step in pre-disaster restoration that can be conducted right away.

Using Imagination and Creativity to Overcome Unexpected Damage

A disaster-resistant community is built not by government but by its residents. Reducing damage by making homes stronger against earthquakes is something that can be realized first through the efforts of members of the public themselves, and then the public’s awareness of disaster prevision will spur government to take action. Efforts to prevent disaster should be considered to consist of 70% self help, 20% mutual aid, and 10% public aid. It is once people have made efforts to help themselves that they will have the leeway to help their neighbors. In this way, a community whose members help themselves is one in which people help each other as well. Efforts toward self-help and mutual aid enable public aid in the form of government support to be effective. The foundation of both self-help and mutual aid is individual effort essentially. Two important elements of such efforts are capabilities of imagination and creativity. The imagination to envision damage that has not yet occurred is essential to see what could happen to one’s own home, life and community. Creativity is the ability to think of what kinds of countermeasures should be taken with regard to such damage and to work out the measures one’s own household will take.

There are two types of unexpectedness. The first involves damage on a scale much greater than that envisioned by the authorities. This is an issue to be addressed by the chief executive: the Prime Minister, governor, or mayor. The other kind of unexpectedness arises when one does not expect to become a victim him or herself. This is a type of unexpectedness that involves each of us as citizens. It is possible to address the unexpectedness of damage on a scale much greater than that envisioned through fostering imagination and creativity on the part of both the mayor and individual citizens. Pre-disaster restoration is an effort to address unexpectedness. In other words, it is my hope that everybody will come to understand that self-help based on imagination and creativity is the only way to overcome the unexpected, and I aim to advance practical research toward this end.

* The information contained herein is current as of December 2014.

* The contents of articles on M’s Opinion are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.