Triggered by two consecutive years of poor harvests and affected by increased consumption due to soaring wheat prices

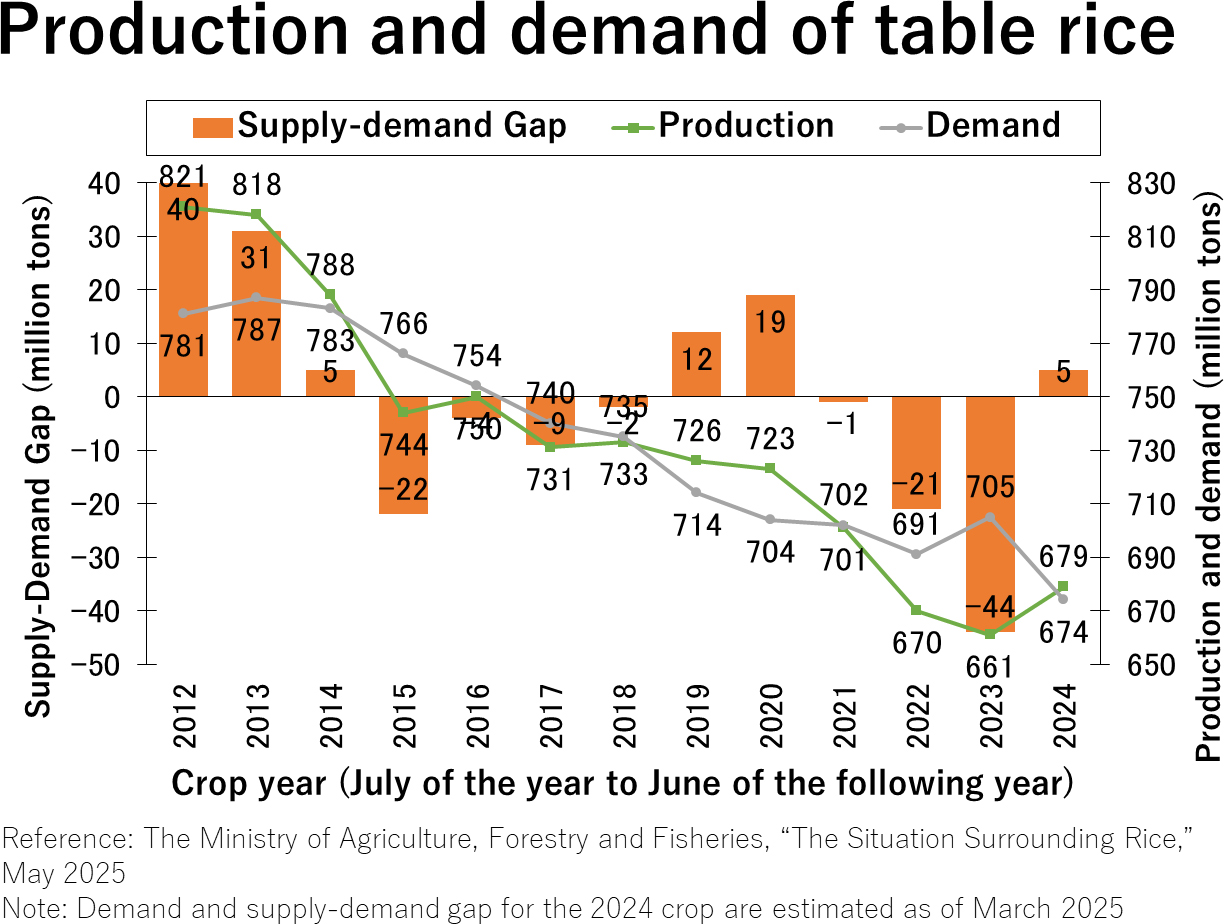

A series of problems known as the Reiwa Rice Turmoil, during which prices soared continuously, were triggered by two consecutive poor harvests of rice in 2022 and 2023. Because the rice harvest mainly begins in September, stocks are at their lowest in August out of the year, but the decline in stocks of the 2024 crop was particularly pronounced, reaching an unusual level.

Moreover, in August of the same year, the Nankai Trough Earthquake Extra Information was issued, which caused a hoarding of rice. Even though the dealers raised their prices because it sold too much, many people tried to buy up more. Accordingly, since September, dealers who had never dealt with rice bought it up at high prices from farmers, resulting in JA (Japan Agricultural Co-operative) being unable to collect rice for the first time.

In addition to the poor harvest for two years in a row, an unusual increase in the consumption of the 2023 rice compared to the previous year also had an impact. The government had assumed and planned for a 100,000-ton decrease in consumption each year due to the aging and declining population, but instead it increased by 140,000 tons. The reason for this is said to be inbound travel and the soaring price of wheat.

Inbound travel, however, could hardly explain it, because even before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were a huge number of foreign tourists, but that did not affect prices. Russia and Ukraine, with their vast granaries, started a war, causing the international price of wheat to soar and the price of noodles and bread to rise, leading to a shift to rice. This would be a persuasive hypothesis to explain the unexpected increase in consumption.

Note that although the 2024 crop yielded about 6.8 million tons, which was about the same as usual, it was not enough to make up for the shortfall of about 600,000 tons caused by poor harvests in 2022 and 2023.

Tariffs on imported rice set exceptionally high to protect domestic agriculture

Due to the shortage of rice, there were arguments that rice should be imported more proactively and requests for additional imports. What is the situation of rice imports in Japan in the first place?

In 1993, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was established to liberalize trade after the war, concluded the GATT Uruguay Round Agreement, effectively obliging Japan to import 770,000 tons of rice every year. However, there was already a surplus of rice in Japan, and the government had implemented a policy of reducing acreage by providing subsidies for the planting of crops other than table rice in rice paddies. So there was an enormous outcry when it was accepted.

Currently, Japan imposes a very high tariff of 341 yen per 1 kg rice imported over these 770,000 tons. According to the estimate published by MAFF in 2005, the tariff rate in percentages amounts to 778%. Tariffs on agricultural products are higher than those on industrial products such as automobiles in every country, but this would be outstandingly high.

As you can see from this, President Trump’s 700% remark is not quite wrong. However, that remark was intended to give an example of tariffs higher than those of the U.S. imposed by some countries and to justify invoking uniform reciprocal tariffs and sectorial tariffs, including those on automobiles. The EU and other countries were criticized as well. The Japanese government set the high tariffs to protect domestic agriculture, but President Trump used it to his advantage.

However, this time the price of domestic rice has gone up so much that profit can be made even with high tariffs, which is increasing private imports. Nonetheless, if the price of domestic rice falls, importing rice will no longer be profitable, and this situation will naturally end and return to the way it should be.

Problem of the program that delayed and prevented progress in releasing stockpiled rice for a short-term solution

In May 2025, after Shinjiro Koizumi took over as the Minister of MAFF, stockpiled rice became available in stores, finally settling the situation. Why did it not distribute smoothly in the market even though the release of stockpiled rice started in mid-March? If the release of stockpiled rice, amounting to 1 million tons, had begun in August last year, when the price of rice soared, such turmoil would not have occurred in the first place. Why didn’t this happen?

Originally, stockpiled rice was intended to address a shortage caused by a disastrous harvest. In the present case, the price soared, but rice was not completely unobtainable. Under the conventional program of stockpiling rice, the release was not allowed in such circumstances, so the rules had to be revised, which delayed the response.

Moreover, in the bidding started in mid-March, the stockpiled rice was sold to collectors such as JA. From there, the rice passed through wholesalers who milled rice in large quantities and intermediate wholesalers who packed rice in smaller bags. The distribution route to retailers was so long that the rice remained out of consumers’ hands.

From JA’s perspective, they are in a position to ship rice after receiving orders from wholesalers. There should also be various reasons, such as not many orders came even though they were waiting, or they could only ship in small batches because wholesalers had limited warehouse space. However, the measures failed to achieve their goal of lowering the soared price of rice by quickly making it available in supermarkets, and as a result, they were unsuccessful.

After that, when Minister Koizumi took over, the channel was changed to selling directly to retailers under discretionary contracts, and some of them had rice in their stores within about three days. The media also pays attention to Minister Koizumi, who has the power to transmit. Meeting with the company presidents and naming the companies creates a competition like whether Don Quijote or Aeon comes first. On the other hand, wholesalers got no press coverage and did not have direct contact with consumers, so I think they were a little less desperate.

There are signs that the price of rice, which did not go down even after releasing the stockpiles from the bidding, is going down after the rice is sold to retailers under discretionary contracts. This suggests that someone stocked it up after all. Koizumi has stated that he will not hesitate to import rice, indicating that he will do so if the hoarded rice is not released. In September, new rice becomes available and the price of old rice will fall, so more hoarded rice will come on the market before the price collapses.

What should be done for a long-term solution about Japan’s excessive acreage reduction policy?

Japan’s excessive acreage reduction policy also plays a role in the recent surge in rice prices.

As a result of promoting agriculture to overcome the food shortage after the war, Japan became self-sufficient in rice around 1965. However, as people became more affluent, the consumption of meat rather than grains increased, which is a common phenomenon throughout the world. The acreage reduction policy was introduced in 1971 to curb the decline in rice prices caused by a surplus of rice, as production increased but consumption decreased. The policy has been in place for more than 50 years, with the benefits of a slight increase in the self-sufficiency rate of wheat and soybeans, much of which is imported, and a slight increase in the price of rice due to a change of crops.

The current production and consumption of rice have decreased by about 40% from their peak. Japan has about 1.8 million hectares of rice paddies, and 1/3 of them no longer grow table rice. However, in rainy and humid Japan, it is difficult to switch from rice paddies to fields, so some farmers shifted to feed rice for livestock. It is true that this was an unexpected crop failure, but if the 1/3 of rice paddies not growing rice had grown table rice, they would have been able to harvest about 3 million tons more. The acreage reduction policy should have room for improvement.

Prime Minister Ishiba had been calling for the abolition of the acreage reduction policy since he was the Minister of MAFF from 2008 to 2009. I was also in MAFF at the time and accompanied the minister on an overseas trip. The acreage reduction policy also has a disadvantage of hindering farmers who want to produce efficiently on a large scale. Prime Minister Ishiba’s belief was that if farmers were to suffer from falling prices in the first place, they should be subsidized to make up for the decline caused by overproduction, not for the reduced acreage.

However, if you are going to disburse the decline in full, you will need a huge subsidy. Currently, about 400 billion yen is spent on acreage reduction. It was estimated in 2009 that it would cost about 800 billion yen if the acreage reduction was abandoned and the decline was compensated in full. On the other hand, limiting the compensation to large-scale farmers will contain the cost to about 300 billion yen, but small-scale farmers would oppose this. As has been argued in the Diet, that would be the focus of the argument.

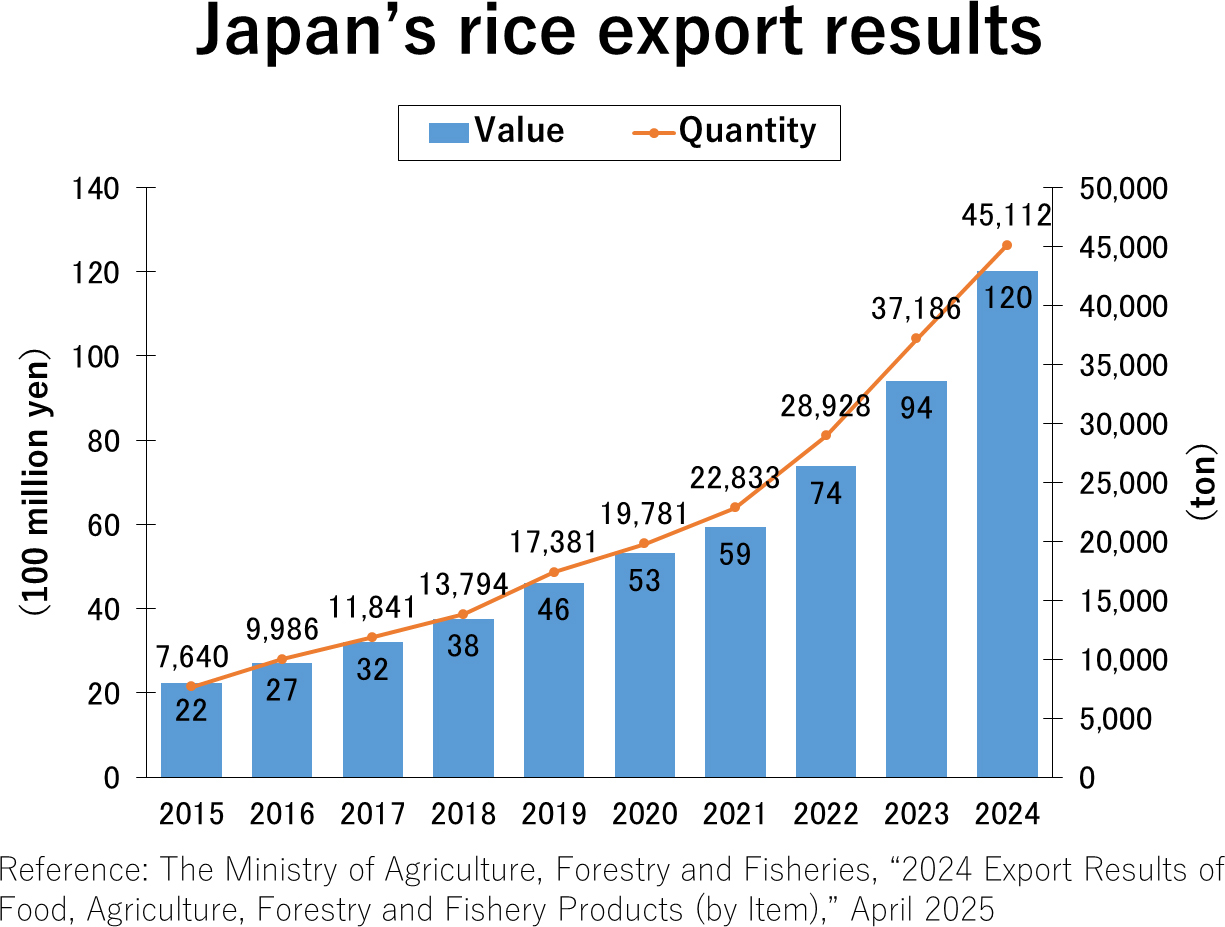

It was estimated in 2009 that abandoning the acreage reduction policy would cause the price of rice to fall to about half of the current level. This would make rice much cheaper than wheat, whose price is soaring, and could lead to more domestic consumption and more exports. Due to the Japanese food boom overseas, rice exports have increased sixfold over the past 10 years. Expensive Japanese rice used to be avoided, but there are quite a few businesses that utilize it because it goes best with Japanese food such as sushi. Lower prices will make it easier to sell overseas. There must be a way to absorb the minuses.

Since rice is an agricultural product that is produced only once a year, the forecast of its yield is often wrong. Up until now, production had exceeded the forecast, but for the first time, it fell below it. Since there are more consumers than producers, the price hike was perceived as great turmoil. However, the rice producers’ true feelings are that they have suffered from low prices due to overproduction and it is not fair to call it “turmoil” only when the price goes up.

In the first place, the reality is that the price of rice is so low that even fairly large farmers barely make money and profit from the subsidy they receive from a change of crops. If the price is not maintained at a certain level, there will be no producers in Japan. Since about 85% of rice farmers are currently elderly, some expect the number of rice producers to decrease drastically around 2040, leading to a rice shortage. If prices remain too low, rice farmers may not be able to sustain themselves and domestic rice may even disappear. Rather than reducing production, I think it would be a way to prepare for the future to pay farmers fair prices.

* The information contained herein is current as of June 2025.

* The contents of articles on Meiji.net are based on the personal ideas and opinions of the author and do not indicate the official opinion of Meiji University.

* I work to achieve SDGs related to the educational and research themes that I am currently engaged in.

Information noted in the articles and videos, such as positions and affiliations, are current at the time of production.